Chain Reaction Research | 2 March 2022

African oil palm expansion slows, reputation risks remain for FMCGs

Although West and Central Africa have been promising regions for large-scale palm oil production, expansion has not gone as planned. Only a handful of companies control industrial palm oil production and will likely drive expansion, but on a smaller scale and at a slower pace than originally anticipated. Nevertheless, these companies have been linked to numerous social and environmental impacts, violating their buyers’ NDPE commitments.

Download the PDF here: African Oil Palm Expansion Slows, Reputation Risks Remain for FMCGs

Key Findings

-

There is substantial discrepancy between oil palm concessions in West and Central Africa and areas ultimately converted for industrial oil palm plantations. Between 2016-2019, Africa’s oil palm concession area dropped from 4.7 to 2.7 million hectares (ha). Of the remaining 2.7 million ha, only an estimated 220,608 ha have been developed into oil palm plantations.

-

The materialization of stranded land risks is linked to land acquisition and community resistance. At least 27 planned oil palm projects, covering 1.37 million ha, have failed negotiations or have been abandoned between 2008-2019. Project failures can have adverse human rights impacts as well as lead to an increase in deforestation.

-

Only five international companies dominate industrial oil palm production in Africa: Socfin, Wilmar, Olam, Siat, and Straight KKM (formerly Feronia). They control an estimated 67 percent of the industrial oil palm planted area with foreign investment and may drive continuous expansion. Risks are most pronounced in Nigeria, where expansion may come at the cost of state natural forest reserves.

-

Socfin and Wilmar, the two largest African operators, are linked to numerous social and environmental impacts on their African concessions. These impacts vary from land-grabbing to loss of social and environmental high conservation values to violence and intimidation.

-

Investors may see risk in African palm oil caused by stranded land and reputation risk. Palm oil buyers and FMCGs linked to escalated cases of land-grabbing and violence against local communities include Wilmar, Olam, Danone, PZ Cussons, FrieslandCampina, Nestlé, and Kellogg’s.

-

Financiers and companies face reputation and regulation risk. FMCGs and financiers with NDPE violations linked to African palm oil supply face reputation risk. Moreover, they will need to comply with upcoming EU supply chain regulation.

African oil palm expansion is not working as planned

The African continent has been considered one of the major promises for oil palm expansion due to the existence of large areas of uncultivated arable land. Triggered by little remaining arable land and tighter environmental regulations, Southeast Asian corporations searched for new frontiers for oil palm expansion. West and Central Africa have become the preferred regions since the early 2000s. Some of the largest Southeast Asian and European producers have moved into Liberia, Gabon, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Cameroon, and Côte d’Ivoire. Reasons for targeting these countries include their large areas of cultivatable land, favorable soil and climatic conditions, the proximity to key markets in Europe and Africa, governments providing easy access to (state-owned) land, low cost of concessions, expected increasing demand from local markets, weak governance, and poor environmental and social oversight due to a recent history of political unrest and violent conflict.

But oil palm expansion did not go according to plan, with substantial disparities between awarded concessions and areas eventually developed into industrial oil palm plantations. An estimated 1.8 million hectares (ha) of land for palm oil plantations have been made available in West and Central Africa since 2008. Nevertheless, large areas have not been developed, in particular in Liberia and Congo-Brazzaville. Estimates in Liberia point to 755,000 ha of oil palm concessions awarded to palm oil companies, with only 7 percent (54,000 ha) developed into industrial plantations in 2019. The Congo-Brazzaville situation is even more extreme, with only an estimated 1,000 ha (0.2 percent out of 520,000 ha) developed into oil palm plantations. While these numbers also relate to the fragility of these states, land tenure insecurities and acquisition difficulties delay expansion plans in other African countries as well, such as Nigeria.

Once the largest global palm oil producer, Nigeria now ranks fifth on the world’s production, among others linked to problematic land acquisition. The country is still the largest palm oil producing country on the African continent. Nigeria was leading the global palm oil market in the 1950s and 1960s, but currently is a net importer from Indonesia and Malaysia, because of Nigeria’s negligence of its domestic palm oil sector. Disincentives for investment in Nigeria include, but are not limited to, an increased focus on petroleum as main source of revenue, land tenure issues, the absence of a palm oil marketing board, illegal cross-border inflows of palm oil, lack of affordable financing, and low-yield seedlings. As the chairman of the Plantation Owners Forum of Nigeria (POFON) puts it: “We have the land, but the challenge is how to take peaceful possession of the land. Even potential investors with requisite financial capital find it difficult to acquire land.”

Oil palm expansion in Africa slowed, plantation area declined

Africa’s oil palm concession area dropped from 4.7 to 2.7 million ha between 2016-2019

A 2019 collaborative effort involving GRAIN and other NGOs reveals the existence of 49 large-scale industrial oil palm concessions in Africa, covering 2.7 million hectares (ha), a drop of 2 million ha compared to 2016. In that year, the organizations documented 4.7 million ha of oil palm plantations through 65 large-scale land deals signed between 2000-2015. The database includes deals only since 2006 that are led by foreign investors, involve over 500 ha of land, and are meant to produce food crops (GRAIN et al. include biofuel deals as food deals).

The pace of land deals has slowed, with no announcements for new, large-scale oil palm plantation projects during 2017-2019. An exception was U.S.-based company Africa Palm Corp. The firm claims to have secured 4.5 million ha of area for palm production, of which 3 million ha are in the Republic of the Congo (with Congolese partner Ngalipomi) and 1.5 million ha in Guinea-Bissau. There is, however, little evidence of implementation to date, with no updates since 2018. The company’s website was inaccessible at the time of publication.

Since 2019, several existing oil palm cultivated areas have expanded, but there is little evidence of new large-scale deals. LandMatrix, a public database on global land deals, confirms the absence, or at least a reduction, of awarding major oil palm land deals in African countries since 2019. Nevertheless, a GRAIN representative told CRR that since 2019, in certain cases, getting insight in land deal developments on the ground has become increasingly challenging, given that in some countries, partner grassroot organizations have had limited access to local authorities and communities due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Stranded land risks in Africa materialize

In 2016, Chain Reaction Research (CRR) emphasized stranded land risks linked to African oil palm expansion, and these risks have appeared to have materialized. There is a huge discrepancy between African oil palm concessions and areas converted to industrial oil palm plantations. While multinational companies reported 2.7 million ha of oil palm concessions in 2019, GRAIN et al. estimates that only 220,608 ha of the total were developed into oil palm plantations between 2009-2019.

Planned oil palm plantations of at least 27 projects, covering 1.37 million ha, failed negotiations or were abandoned between 2008-2019. For instance, in Cameroon, negotiations for palm oil projects of Sime Darby (deal size 300,000 ha) and Cargill (deal size 50,000), both initiated in 2011, failed. Also in Cameroon, Biopalm Energy, a subsidiary of Singapore’s Siva Group, saw its three-year provisional concession of 200,000 ha expire in 2015, without Biopalm starting operations. In Nigeria, only one project survived from the six projects that received the second largest funding from the World Bank for palm oil investments between 1975-2009. The rest went bankrupt. In the DRC, the Canadian Feronia and the Chinese ZTE abandoned their palm oil projects. In Liberia, an 80,000 ha intended concession of Malaysian Kuala Lumpur Kepong Berhad (KLK) failed in the negotiation stage, and another intended 55,289 ha concession was abandoned. Moreover, there are numerous examples of failed negotiations and abandoned palm oil projects in other African countries.

Reasons for delayed, failed, or dropped expansion plans vary and include community resistance to expansion on their traditional lands. Oil palm growers experience considerable operational risks and costs from violent community conflicts, and many African communities have been successful in their resistance to oil palm development. An earlier CRR report highlighted how palm growers that cannot effectively mitigate risks and compensate for the loss of social and cultural values from oil palm expansion will likely experience enduring complaints and conflicts with local communities. Other reasons for abandoned projects include the lack of experience and capacity of several Southeast Asian and European producers targeting African countries, as well as the manifestation of regulatory, operational, and financial risks.

Project failures can have social and environmental sustainability consequences, as Sime Darby’s 2020 divestment from Liberia demonstrates. While the Liberian government awarded the company a 220,000-ha concession in 2009, only 10,300 ha were developed in 2020. The case emphasizes how companies and investors could face environmental, social, and governance (ESG) risks related to deforestation and human rights. A sudden shutdown of such land-related projects can increase the risk of adverse human rights impacts. Divestment could also indirectly lead to an increase in deforestation, as former workers look for alternative sources of income.

A handful of companies dominate African industrial palm oil production

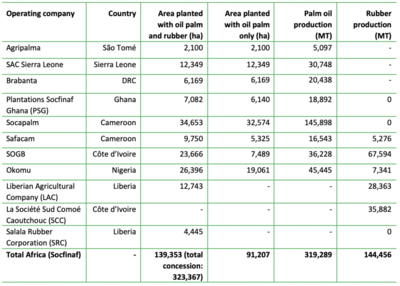

Only five companies control an estimated 67 percent of the large-scale planted industrial oil palm plantations in Africa: Socfin, Wilmar, Olam, Siat, and Straight KKM. The latter took over Feronia’s shares in Plantations et Huileries du Congo (PHC) in 2020 to avoid the company’s bankruptcy. The combined oil palm planted area in ten African countries of these five companies is 309,636 ha (Figure 1). The total planted area under large-scale industrial oil palm plantations throughout the African continent was estimated at 462,665 ha in 2019. Current expansion priorities include Cameroon, the DRC, Congo-Brazaville, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone.

Figure 1: The five largest oil palm plantation companies in Africa

Investments and expansion plans of these five companies expose them to high risks of being linked to negative social and environmental impacts from African oil palm development. In all African countries where Socfin is operating (Figure 1), the company is reportedly pursuing expansion, as illustrated by research and statements in the DRC, in Côte d’Ivoire, and Ghana. Also, Wilmar is mentioned as having expansion plans for many of the African countries where it is active, such as in Uganda and Nigeria. In response to a draft version of this report, both companies said that these statements are not necessarily true, and that the main source of this information, the report by GRAIN et al., does not substantiate such assertions. While Wilmar does not confirm whether it is pursuing expansion in Africa or not, Socfin shared its 2018-2020 data, which shows that the company has not expanded its net planted area with oil palm on the continent during those years. It is unclear whether the company has had expansion plans on its African oil palm concessions since 2020.

Olam Palm Gabon states that it has “no plans for further expansion of palm production at this time,” but unclear is whether the company has expanded oil palm planted area between 2019-2021 or plans to expand in the near future. Siat Group will mainly expand in Nigeria, where its firm Siat Nigeria reportedly owns 16,000 ha of oil palm plantations that are currently covered with old, unproductive oil palm plantations. To date, 5,000 ha have been replanted. Feronia’s PHC plantation has just come under control of an investment fund, and it is still unclear if there are any expansion plans.

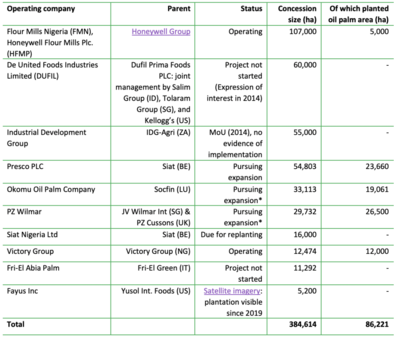

Expansion risks at the cost of natural forests most pronounced for Nigeria

The risks of expansion are most pronounced in Nigeria, where palm oil production is projected to grow, attributed to increased private investments and the Nigerian government’s efforts. Since 2019, the Nigerian government has aimed to revive the ailing oil palm sector, with planned investment of USD 500 million. Nigerian palm oil production is expected to grow nine percent from 1.28 million metric tons (MT) in 2020/21 to 1.4 million MT in 2021/22 (Figure A, Appendix). Besides Nigeria, only Cameroon shows a trend of recent increasing growth rates of palm oil and palm kernel oil production, while the other palm oil producing African countries remain at constant levels (Figure B, Appendix).

Expansion plans appear to come at the cost of state natural forest reserves. The Nigerian government is actively distributing state forests to international companies for oil palm expansion. Reportedly, under the Edo State Oil Palm Production (ESOP) program, the state government has allocated 120,000 ha from its forest reserves to companies for cultivating palm oil. Edo State is one of Nigeria’s major oil palm cultivation areas. While oil palm investors are “required to nurture and develop 1,000 ha as natural forest for every 4,000 ha of land devoted to oil palm production,” the palm oil sector has had harmful effects on Nigeria’s forests in recent years. In response, Socfin stated that: “The State Government has de-reserved the 120,000 ha of degraded forest that has been decimated by illegal loggers for the European timber market,” adding that “No oil palm or tree company is permitted to obtain any land in these areas if they are not certified under RSPO or FSC first.”

Available loans largely benefit large-scale industrial growers, with Okomu Oil Palm Plc (operating company of Socfin) and Presco Plc (operating company of Siat) recently expanding their production. While Nigeria’s palm oil industry is dominated by smallholder farmers which account for approximately 80 percent of local palm oil production, the remaining 20 percent is covered by industrial plantations that hold considerable market share. Government investments have supported large players such as Okomu Oil Palm Company to expand its “footprints in the sector”. Okumu has increased its oil palm planted area from 18,879 ha in 2018 to 19,061 ha in 2019 and is expected to double its production from 40,000 MT in 2021 to a forecasted 80,000 MT per year by 2025. Despite being the intended target group, small farmers reportedly cannot access these funds. According to Socfin, “The challenge for smallholders is to securitize their assets with the bank but to address this the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), NGOs and industrial actors, including Socfin, are working on a loan scheme for tree crop smallholder farmers.”

There is less evidence that the expansion plans of De United Foods Industries (Dufil) and PZ Wilmar in Nigeria have led to concrete new areas planted with oil palm (Figure 2). Dufil Prima Foods, the parent company of Dufil, a joint management with Indonesian Salim Group, has succeeded in the acquisition of 17,954 ha of land in the Ekiadolor Forest Reserve from the Edo state government for oil palm cultivation. But the company is still in the process of paying compensation to farmer communities. A recent High Conservation Value-High Carbon Stock Approach (HCV-HCSA) assessment was found satisfactory in December 2021, after two rounds of unsatisfactory evaluations. There are no indications that the planting has started. While PZ Wilmar, a joint venture (JV) between Wilmar International and PZ Cussons, has built an edible oils refinery in Lagos state, the status of its current plantation operations and expansion plans is unclear.

Socfin, the largest operator in Africa, has a gap between responsible policies and practices

Africa’s largest palm oil producer is Socfin Group, a Luxembourg-based holding company involved in oil palm and rubber production in Asia and Africa. The company has about 383,000 ha of concessions in ten countries. Socfin Group, which consists of major financial holdings Socfin, Socfinaf, and Socfinasia, is 39 percent held by the French group Bolloré and 54 percent held by the Belgian businessman Hubert Fabri. Socfin was a European agribusiness company during the colonial period and has largely expanded its plantation territory through privatization of African state plantation companies. The group reported a consolidated revenue of EUR 605.3 million in 2020 and employs 48,283 people. The group says it is committed to promoting biodiversity and eliminating deforestation.

In Africa, Socfin Group is most present in Central and West African countries Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, DRC, Ghana, Nigeria, São Tomé-et-Principe, and Sierra Leone, producing over 300,000 MT of palm oil. It also operates in Indonesia through its subsidiary Socfindo, and in Cambodia as Socfin KCD and Coviphama. Altogether, the group produced 503,926 MT of palm oil and 160,411 MT of rubber in 2020. When considering its operations only on the African continent, Socfin produced 319,289 MT of palm oil (64 percent of total production), and 144,456 MT of rubber (90 percent of total production) in 2020 (Figure 3). The company planted a total of 139,353 ha of oil palm and rubber in Africa, of which more than half is for palm production (91,207 ha).

Figure 3: Socfin oil palm and rubber plantations in Africa

Environmentalists highlight the gap between Socfin’s “responsible management policies” and the reality of social and environmental impacts on and near their plantations. Nearby residents and campaign organizations say that the recent Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) certification of Socfin’s Socapalm plantations in Cameroon and its Okomu’s plantation in Nigeria are “based on fake processes,” “incredible” and “examples of the RSPO’s shortcomings.” Social and environmental issues reported on Socfin’s concessions in Africa include:

- Socfin’s Socapalm (leased) plantations in Cameroon are linked to land grabbing and exploitation of local communities. Local villagers report atrocities in and around the plantations such as lack of access to land to cultivate food and sexual abuse of women. Moreover, there have been lawsuits against journalists who tried to report on social and environmental injustices on the plantations.

- For more than a decade, Socfin’s Okomu Oil Palm Company in Nigeria has been in conflict with several communities inside its concession. The dispute is over land ownership and usage rights in the reserve, including displacement and alleged severe violence (e.g. burnings) by security staff and Nigerian soldiers against villagers. In 2015, five company staff members were killed by aggrieved residents of the area.

- In Sierra Leone, an estimated 9,000 people have been affected by Socfin’s oil palm plantation in Malen Chiefdom, Pujeun District. This reportedly involves deforestation, land acquisition conflicts, and inadequate crop and land compensation.

- In 2021, Socfin is accused of evading taxes in Africa and shifting profits from Africa to Switzerland.

In response to a draft version of this report, Socfin denied the accusations in the cases above, citing various reasons. For instance, Socfin responded that “any allegation of land grabbing done by Socapalm is irrelevant” as no expansion occurred since the concession was taken over from the government in 2000. Moreover, the Okomu forest reserve was “de-reserved at the time of oil palm planting, and when the federal government of Nigeria started oil palm planting, there were no communities in the forest reserve, since no community were permitted to reside, as stated in law.” For the Sierra Leone case, the company said that “the land leasing process was carried out in full compliance with national laws and regulations and international standards,” and that “FPIC was done with all relevant stakeholders. Finally, the company stated that “Socfin has always ensured strict compliance with the rules in force and does not enjoy any tax privileges in Switzerland.”

In June 2021, a complaint was filed to the accreditation organization SCS Global Service for issuing Socfin’s SOGB in Côte d’Ivoire with an RSPO certificate though the certification process was allegedly flawed. Socfin’s Société des Caoutchoucs de Grand Béréby (SOGB) contracted SCS Global Services to conduct the RSPO certification assessment of its plantation and mill located in the Bas Sassandra District in Côte d’Ivoire. A recent study commissioned by Milieudefensie concluded that the certificate is “based on a flawed consultation process and does not assess relevant concerns in land rights, pollution and livelihoods.” In response, SCS denied the majority of the allegations and said that no recent expansion of the SOGB farm was observed during the RSPO audit in September-October 2020.

Wilmar linked to land grabbing, human rights violations, deforestation

Wilmar International, a leading agribusiness company in Asia and Africa and the world’s largest palm-oil trader, expanded its footprint to 16 countries on the African continent since entering in 2000. The company’s total reported planted area under its oil palm plantation and sugar milling segment in Africa and Asia is 232,053 ha. This total is comprised of areas controlled through joint ventures (46,000 ha), smallholder schemes (35,276 ha), and associates (157,515 ha). The company directly owns three palm oil refineries in Africa, along with eight refineries indirectly through its associated companies. Wilmar, one of the largest producers of edible oils, soaps, and detergents on the African continent, adopted the first palm oil industry NDPE policy in 2013.

In Côte d’Ivoire and Liberia, Wilmar sources its palm oil supply through the SIFCA Group, which is 27 percent owned by and supported by Wilmar. SIFCA Group is a non-listed Ivorian agro-industry company active in palm oil, rubber, cocoa, cotton, sugar, and coffee. In Côte d’Ivoire, SIFCA Group runs its oil palm plantation operations under Palmci, while in Liberia, SIFCA Group is active in oilseeds through the Maryland Oil Palm Plantation (MOPP).

Wilmar, in response to a draft version of this report, asserted that it “does not represent the SIFCA Group” and that “based on the shareholding structure of SIFCA, the attribution of SIFCA’s plantation areas and operations in the draft report in numerous sections to Wilmar is factually inaccurate and misleading.”

CRR considers three reasons that justify linking the actions and operations of SIFCA Group to Wilmar:

- -Wilmar holds a 27.06 percent stake in SIFCA SA through Wilmar’s wholly owned investment holding company, Nauvu Investments Pte. Ltd. (“Nauvu”). In 2018, Wilmar bought out Olam’s shares in Nauvu (Figure 4);

- -Wilmar sources 100 percent of its palm oil in Côte d’Ivoire from SIFCA&rsqu