In Liberia, human rights have allegedly been violated on rubber plantations managed from Switzerland. Instead of taking up mediation offers, the Socfin group prefers to act against its critics.

By Jan Jirát

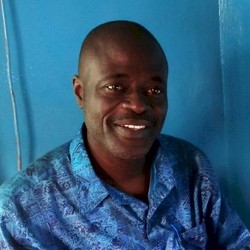

Frank Sainworla is sitting in his office in Monrovia, the capital of the West African state of Liberia, and can be heard perfectly over his cell phone. Three years ago, the renowned 46-year-old journalist founded the independent media platform Public Trust Media Group, which has now a reputation as an important platform critical of the government. But this is not going to be about his everyday work: “In the end, it is a subservient state that puts itself at the service of a corporation instead of protecting its citizens, who are exploited by that corporation.” This is how Sainworla sums up a major research project he conducted this summer on behalf of the Swiss NGO Bread for All (BFA).

The Liberian journalist spent several days with his colleagues William Selmah and Edwin Fayiah on the plantations belonging to the Salala Rubber Corporation (SRC) and the Liberian Agricultural Company (LAC) in the interior of the country, both thousands of hectares in size. This is where rubber is cultivated for the production of car tires. The plantations are owned by the Luxembourg-based Socfin Group (see “The Plantation Group” below). The trade of this Liberian rubber and the management of the two plantations are handled by two Swiss subsidiaries based in Fribourg: Sogescol and Socfinco.

The special thing about Sainworla’s research is the time when it starts. For once, it was not a matter of uncovering and documenting grievances, because BFA had already done so at the beginning of 2019. Rather, the focus was on the question of how a corporation deals with grievances that are already public and with attempts that are made to hold it accountable. This much in advance: “Our work remained limited. The plantation managers refused to talk to us at all,” says Sainworla. The rubber plantations themselves were like protected zones swarmed with security guards. “It was not always possible to have undisturbed conversations with plantation residents.”

A conflict instead of resolution

BFA published an eighty-page study on Socfin’s rubber plantations in Liberia in February 2019. In cooperation with several Liberian organizations, including Green Advocates International, representatives of the organization had visited both plantations several times and talked to over one hundred affected people. Their findings: Numerous farmers were driven from their fertile agricultural land as a result of the expansion of rubber monocultures. Holy sites were also destroyed in the process. Access to water had deteriorated. Furthermore, several women reported that they were repeatedly subjected to sexual violence by subcontractors and, in some cases, by plantation security guards. “The statements from many people who live on or near the plantations suggest a climate of fear,” the study’s summary says.

Socfin immediately denied the accusations, calling them “massively exaggerated, if not incorrect”. The company sees itself as a benefactor, which after the devastating civil wars between 1989 and 2003 was urged by development agencies such as the World Bank to rebuild the untapped potential of Liberia’s economy: In the process, it had also built schools, clinics and houses.

In Switzerland, the BFA report was initially well received by the media. A daily newspaper (Tagesanzeiger) vividly illustrates the connection to the Responsible Business Initiative (RBI): If a Swiss court decides that there is an economic dependency between the Socfin Group’s subsidiaries in Switzerland and Liberia – the BFA study outlines such a dependency in detail – then, according to RBI, the people in Liberia affected by human rights violations and environmental damage could personally file a civil law suit in Switzerland. An emission by the National Swiss TV (SRF “Rundschau”) did also report on the Liberian Socfin plantations in February 2019, but had later withdrawn its contribution from the net, on its own initiative. Their explanation was: “In the article, Socfin was held responsible by protagonists for the eviction and destruction of the village of Tartee in 2010. However, as it turned out in the follow-up to the report, the eviction of this village took place years earlier, at a time when the rubber plantation was not yet under the management of the Socfin Group”.

In fact, BFA did make a mistake on this specific point – it has long since been corrected in the study. However, the organization is sticking to the numerous other accusations against Socfin. But the damage has been done: RBI opponents – above all Ruedi Noser, a member of the National Council of States from Zurich – have accused BFA since then of violating the due diligence. This dispute is still a topic of discussion in the media today, whereas for long no one has reported on Socfin’s conduct on its Liberian plantations.

Active corporation – passive government

But Switzerland does not remain the only scene. In May 2019, 54 affected people from 22 villages filed a complaint with the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the World Bank’s lending agency for the private sector. In 2010, the IFC granted a loan of ten million US dollars to the Socfin plantation SRC. Subsequently, the IFC ombudsman sent a mission on site and listened to both parties. It then made a mediation offer to both parties. While the complainants – the people from the villages – accepted the offer, Socfin declined. According to Socfin, the ombudsman’s office was biased. The proposed mediator, James Tellewoyan, was an acquaintance of the director of the NGO Green Advocates International. According to Sainworla, however, the accusation was flimsy: Tellewoyan also knows SRC’s personnel officer personally. The IFC ombudsman has now scheduled an in-depth investigation to determine whether SRC has indeed complied with the environmental and social requirements. The corresponding report should be available in summer 2021.

As Sainworla points out in his research, Socfin is not simply refusing a mediation: “Since 2019, the company has apparently been building up a counter-organization to its critics, the Citizens Union. The founding of this pro-SRC group, which is made up mainly of the local elite, has led to a situation where some of the village communities are now divided,” says Sainworla. In addition, the Citizens Union has succeeded in undermining the legitimacy of the organizations that lead the resistance against Socfin, for example through a media campaign via the national news agency, which reports that SRC and the local community now coexist peacefully. The news agency apparently places itself entirely at the service of the SRC, according to Sainworla: “What was particularly bizarre was the moment when the SRC referred us to the local correspondent of the national news agency with our inquiries to the group.”

But the most disturbing aspect of the research is that the national concession office in Liberia claimed to know nothing about the complaints of the local population, although it is responsible for land disputes. “We can prove through old newspaper reports and mails from the resistance organizations that the government agency definitely knows about the complaints. But the government has not yet taken any action in this matter.”

“It needs the pressure from outside”

This newspaper confronted Socfin with the research results of Frank Sainworla. The feedback came late and only after several inquiries. “Unfortunately, we are not in a position to give you detailed answers at this time” the plantation company told us. On the one hand, investigations were currently being conducted by the IFC ombudsman’s office, which is why this office should be contacted after all. “Also, we don’t want to be involved in a political campaign surrounding the RBI vote,” Socfin continued, complaining about the short time available for feedback.

Meanwhile, Frank Sainworla looks hopefully to Switzerland. “Approval of the Responsible Business Initiative would be a very important signal. Here we experience every day what it means to be caught up in a cycle of institutionalized irresponsibility,” says Sainworla. Corporations evade all responsibility; the government looks away or even supports them. What they need here are clean, fair legal procedures. “The RBI is a door opener for us,” says Sainworla at the end of the interview.

Francis Colee is also looking forward to the RBI vote. The 47-year-old director of the NGO Green Advocates International talks himself into a rage on his cell phone when he talks about the Socfin complex: “After the end of the civil war almost two decades ago, everything here was down, economically and politically. This is an easy prey for companies like Socfin, that at such moments aggressively push their way into these markets and secure concessions and contracts – covered and supported by agencies like the World Bank. If resistance then forms among the local people, they always say: After all, we have invested here, we are only protecting our investments.” Colee considers the RBI to be an “extraordinary idea” because reality had shown that corporations were only interested in their profits. “Without pressure, any investment in a country like Liberia remains a pure business matter, while the social and human rights aspects of this investment are completely ignored. The RBI could change that.”

Socfin (Société financière des caoutchoucs) is a listed group based in Luxembourg, which operates rubber and palm oil plantations, mainly in West Africa and Southeast Asia. According to its own information, the group, founded in 1909 with a colonial past, employs over 47,000 people and manages plantations covering an area of 193,000 hectares. The main shareholders are the Belgian businessman Hubert Fabri and the French billionaire Vincent Bolloré, owner of the conglomerate of the same name.

Socfin is under criticism in several countries for human rights violations, environmental damage and accusations of corruption. A vivid summary of the Socfin complex is available on the “Mongabay” platform.