Korea Times | 12-04-2009

Dave Durbach

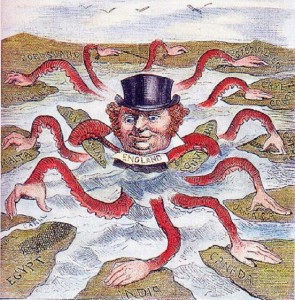

Korea Times Correspondent JOHANNESBURG ? South Korea is at the forefront of a new global trend. Unfortunately, it's nothing to be proud of: a global power struggle for food security that threatens the sovereignty of poorer nations and the livelihoods of rural communities in Africa, South East Asia and South America. Ironically, Korea was in a similar position not so long ago - a poor population living off the land, a fragile economy at the mercy of larger powers. As everywhere else, however, newfound power has given rise to a sense of entitlement and self-importance, often at the expense of the poorest of the poor. As one of the world's most densely populated and fastest developing nations, land in South Korea has become a scarce commodity. Farmland and forests have rapidly made way for factories, roads and new urban development over the past 15 years. As a consequence, Korea has become increasingly dependent on food imports. Hard hit by a global financial crisis and rising international food prices, food security has become a key concern for the Lee Myung-bak administration; finding a solution is an urgent national imperative. The government's approach to the problem appears to be yielding results, with reports in August predicting that despite shrinking farmland on the peninsula, Korea would enjoy a 10 percent increase in rice production this year, the first since 2005. The most famous and controversial example is Madagascar, where last year Daewoo announced plans to lease 1.3 million hectares of land for 99 years. Roughly half of the country's arable land, as well as rainforests of rich and unique biodiversity, were to be converted into palm and corn monocultures, producing food for export from a country where a third of the population and 50 percent of children under 5 are malnourished, using workers imported from South Africa instead of locals. Those living on the land were never consulted or informed, despite being dependent on the land for food and income. The controversial deal played a major part in prolonged anti-government protests on the island that resulted in over a hundred deaths and the removal of President Marc Ravalomanana from office. His successor Andry Rajoelina immediately revoked the deal upon taking office, although reports by Rainforest Rescue reveal that for some time after the coup, Daewoo continued to surreptitiously hold some 218,000 hectares of appropriated land. When the debacle finally seemed to have died down, reports from the nearby east African nation of Tanzania announced that Korea was in talks to develop 100,000 hectares for food production and processing, to the tune of between 700 and 800 billion won. Apparently wise to the upset caused in Madagascar, this deal seemed more mutually beneficial, with the state-run Korea Rural Community Corp (KRC) reportedly offering technical assistance to local farmers, while using only half the land to produce processed goods such as cooking oil, wine and starch for export to Korea. While the KRC and Korean media were quick to proclaim the deal done and dusted, Tanzanian politicians remained reluctant to confirm that anything had been finalized. If the project does go ahead next year, the "agricultural complex" will be the largest single piece of agricultural infrastructure Korea has ever built overseas. Africa is not the only target. Private companies and local provincial governments have made deals to procure farmland in eastern Siberia, Sulawesi in Indonesia, Mindoro in the Philippines (94,000 hectares), Cambodia and Bulgan in Mongolia. A few weeks ago, the government announced its intention to invest 30 billion won in land in Paraguay and Uruguay. Discussions with Laos, Myanmar and Senegal are also reportedly underway. In all cases, it is proving cheaper to farm overseas than to import food. Not surprisingly, however, by paying for the land instead of the labor or product, local communities are effectively being shut out of the process. That Korea is no longer "importing" this food that is being grown overseas implies that this land is effectively Korean. This amounts to agricultural imperialism. As during 20th century colonialism, those with money and power are calling the shots. Local farmers and indigenous communities, meanwhile, are up in arms at being cut off from their land and critical of their leaders who are complicit in these deals, unsettling local politics in the developing countries concerned. Korea is not alone here: other Asian powers are embarking on similar ventures. China is seeking 2 million hectares in Zambia for biofuels; Saudi Arabian investors are spending $100-million for land in Ethiopia, $45-million in Sudan and millions more for 500,000 hectares in Tanzania; Libya has secured 100,000 hectares in Mali for rice; Qatar, 40,000 hectares in Kenya; India's Yes Bank is investing $150 million to start producing wheat and rice on between 30,000 and 50,000 hectares of land by 2011. Clearly, poor regions where communities don't have legal tenure over land are most vulnerable. Beyond Africa, the Philippines has so far been hardest hit by foreign land grabs, with Japan, China and Qatar leasing millions of hectares from the Filipino government, triggering widespread protests and an official enquiry. What all cases have in common is that in order to maintain the development trajectories and over-consumptive lifestyles of nations either over-populated or short on natural resources, food and biofuels for the rich are being prioritized over human rights, natural ecosystems and political stability for the poor. In the past year, farmland has become as strategic a resource as oil fields or uranium mines. It is estimated that more than 20 million hectares of farmland in Africa, Latin America and Asia have already been snapped up by foreign governments and companies. Unfortunately, local leaders cannot be trusted. In Madagascar, for example, soon after the Daewoo deal was shelved, it emerged that Malagasy officials had negotiated the lease of 465,000 hectares of farmland to Mumbai-based Varun International to grow rice for India. Unless global measures are put in place to stop this new colonialism, and if Korea backs out of agreements, other nations will simply step into the breach. The official spin on it is that South Korea is starting to "give what they really want rather than what you want to give," by investing in agriculture rather than IT, for example. It should be clear by now, however, whose interests are really being served. For Korea, this approach may be more cost-effective than relying on imports, but the question remains: profit at what cost? Korea, or any other country for that matter, has no right to interfere in the sovereignty or stability of another country. Power brings responsibility, not entitlement. [email protected]