Wall Street Journal | 11 April 2023

Groundwater gold rush

By Peter Waldman, Sinduja Rangarajan and Mark Chediak

Graphics by Jeremy C.F. Lin and Kyle Kim

Photos by John Francis Peters

As storms battered California in March, the state’s inland breadbasket erupted with almond blossoms. It happens every year. The Central Valley—the source of 40% of America’s fruit and nuts—explodes in a riot of pink and white blooms. This year petals fluttered off branches into raging irrigation ditches that only a few months earlier had twisted across the dry dust like coils of snake molt.

California has a temporary reprieve. At the Woodville Public Utility District, 60 miles southeast of Fresno, Ralph Gutierrez has watched these cycles of flood and drought for decades. Gutierrez, 65, who grew up picking tomatoes and grapes with his parents in the nearby fields, has spent the past 43 years operating water systems for some of the poorest communities in the state. He’s a well whisperer. Brawny, with a tattooed forearm, a silver belt buckle and Western boots, Gutierrez coaxes water from stone aquifers that have been hammered for years by agricultural pollution and overpumping.

He took over Woodville’s 500 or so household hookups in 2001, when the water table beneath the small farmworker community’s well field was about 100 feet below the surface. The district’s two community wells, powered by electric pumps, produced ample clean groundwater for residential taps. Since then, California has experienced its driest pair of decades in 1,200 years, and the water level has dropped to almost 200 feet. One Woodville well dried up and cracked two years ago. The second was shut down because of nitrate contamination.

Last year almost 1,500 domestic wells went dry statewide, and the state auditor reported almost a million Californians had no safe drinking water in their homes. Today the people of Woodville drink bottled water.

This winter’s record storms, a welcome break from drought, lifted Woodville’s water level 18 feet. It will take decades of wet winters to refill the aquifer. For drought is only part of California’s water woes.

The other part unspools outside the window of Gutierrez’s white Toyota Tundra, on a drive through Woodville’s outskirts. Each side of the road is covered in dense thickets of almond, pistachio and walnut orchards that have grown to dominate the landscape in the past few decades. The nut trees are known as “permanent crops,” because they need copious, year-round irrigation over the course of their 30-year life span. That’s in contrast to row crops such as tomatoes and lettuce, or silage like corn and hay, which can be fallowed to save water during drought.

The owners of the unmarked groves are a mystery to Gutierrez. Every few miles, huge U-shaped nozzles stick up, spouts for disgorging water extracted from deeper and deeper underground for California’s nut juggernaut. The prodigious pumping has helped drop the water table in the San Joaquin Valley, California’s food belt between Sacramento and south of Bakersfield. The decline has deprived many shallower wells belonging to small farmers and poor communities such as Woodville of sufficient water supplies.

“Deeper pockets, deeper wells. That’s what’s basically going on here,” Gutierrez says, growing agitated as the endless rows of trees whiz by. “Whoever is doing this doesn’t give a damn about the small people.”

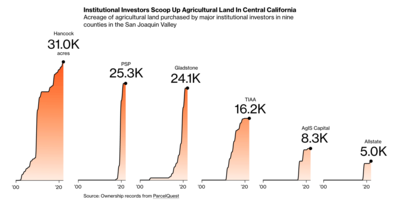

The invisible hand, it turns out, belongs to the long arm of investors in New York, Toronto, Zurich and other financial capitals. Some of the world’s largest investment banks, pension funds and insurers, including Manulife Financial Corp.’s John Hancock unit, TIAA and UBS, have been depleting California’s groundwater to grow high-value nuts, leaving less drinking water for the surrounding communities, according to a Bloomberg Green investigation. Wall Street has come to Woodville, wringing it dry. Since 2010, six major investors have quadrupled their farmland under management in California, to almost 120,000 acres in all, equivalent to a third of all the cropland in Connecticut. Despite epochal drought, these companies have fueled the growth of permanent crops, disregarding some of the most basic principles of sustainable investing.

Much has been made of the water use of local farmers and industrial-scale agribusinesses such as California’s biggest nut farmer, Wonderful Co., but the growing role of institutional investors in the state’s water crisis has gone largely unnoticed. Over the past decade, the financier-farmers have poured millions of dollars into digging deep wells, expensive capital projects that many communities couldn’t dream of matching on their own. In a presentation to investors obtained by Bloomberg Green, one company said it will eventually have to dial back its groundwater pumping yet can still reap handsome returns before that day comes.

Since the start of 2019, one of every six of the deepest wells in the San Joaquin Valley has been drilled on land owned or managed by outside investors, according to Bloomberg Green’s analysis of state well completion reports through August 2022. Of the landowners that have drilled the greatest number of deep wells since 2019, two of the top three are institutional investors: TIAA and the Public Sector Pension Investment Board of Canada.

This rush for water is an outgrowth of a decades-long bet on farmland by investors who see food cultivation as an asset class virtually assured of appreciating in a warming, more populous world. Globally, large investors and agribusinesses have snapped up about 163 million acres of farmland in more than 100 countries in the past 20 years. The land grab has given rise to a grab of an even scarcer global commodity: water. In a bid to ensure thriving investment portfolios, some of the world’s largest financial entities have amassed control over lakes, rivers and underground aquifers in places from California to Africa, Australia to South America, giving them outsize roles in managing an endangered resource that’s the basis of life on Earth. The trend has contributed to shifting hydrological patterns that stand to permanently disrupt communities’ access to fresh water. Local populations are paying the price in drained wells, high water bills and contaminated water supplies.

Deep wells drain shallower wells, a law of hydrodynamics that’s exacerbated social inequities in California and hastened the desiccation of the state’s Central Valley. “California’s groundwater history is one of modest replenishment during these very wet periods, followed by much greater losses during the ensuing droughts,” says Jay Famiglietti, a former senior hydrologist at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who’s now a global futures professor at Arizona State University.

The impact of overpumping is permanent. The practice has caused much of Central California to sink at varying rates for a century, especially during drought, when farmers’ excessive groundwater extraction causes the subterranean clays to dry out and compact. In the past decade, parts of the San Joaquin Valley have dropped as much as a foot per year, according to the US Geological Survey. Subsidence, as the sinking is called, has damaged bridges, canals and other infrastructure that will cost billions of dollars to fix, the state says. The aquifers themselves are irreparable. Many groundwater basins, when drained, never recover their former storage capacity, hydrologists have found. “Groundwater in California has been treated as an extractive resource—you pump and hope for the best,” says Graham Fogg, an emeritus professor of hydrology at the University of California at Davis. “Capitalism is driving this. Investors don’t care, because in 10 years they can make all the money they want and leave.”

Nut trees gained luster for investors about 20 years ago, spurred by the surging popularity of low-carb, high-protein diets such as South Beach and Atkins. From 2001 to 2006, annual US almond consumption grew more than 25%, to over a pound per person, according to the US Department of Agriculture.

Most California nut growers are still local farmers. About 90% of the state’s 7,600 almond farms are family-owned, according to the Almond Board of California, the industry’s marketing arm. The most prolific deep-well driller in the past few years, by far, is Wonderful Co. But as Central Valley temperatures warmed and winters grew drier, institutional investors proliferated like beetles.

By 2010, Hancock Agricultural Investment Group was telling its institutional clients that permanent crops would offer attractive returns, as well as a potential hedge against inflation. Nut farming was largely mechanized, which promised to keep labor costs low. Drip irrigation and other technologies were boosting yields. Exports to Europe and Asia were soaring. Investing in crop land was a bet on diminishing global water supplies, Hancock predicted.

Neither extreme drought nor California’s first groundwater regulations in 2014 would slow the nut boom. Since then, the state’s almond acreage has exploded 50%, while plantings of pistachios, which can withstand drier conditions than almonds, have expanded almost 90%.

Institutional investors piled in. From 2015 through 2019, TIAA directed at least $258 million into about 8,600 acres of California nuts, grapes and row crops. Hancock, from 2016 through 2021, plunked down more than $67 million of investor funds on at least 6,500 acres of permanent crops and other produce. And Gladstone Land Corp., a publicly traded real estate investment trust (REIT), invested $518 million to buy 23,000 acres of mostly almonds and pistachios from 2015 to 2021, which it leases to local farmers. Other institutional buyers included Allstate Insurance, Prudential Financial and the Mormon church, whose Farmland Reserve has invested about $60 million in some 1,500 acres of California nut orchards since 2016.

It’s impossible to apportion blame, between drought and deep extraction, for any one well’s demise. Most of California’s failed water systems are a result of contamination—often a consequence of rampant agricultural drilling, propelled by drought. Deep wells suck surface contaminants such as nitrates from farm runoff down into the aquifer, where the plumes, at higher concentrations because of drought, are pumped into household and community water systems. Tapping deeper groundwater for drinking supplies isn’t an option for poor communities, as it can cost about $350,000 to drill a 1,000-foot well. It’s also dangerous. Beneath about 600 feet, many Central Valley water basins contain arsenic, a naturally occurring carcinogen.

In 2014, California became the last Western state to regulate groundwater pumping. The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act requires balancing recharge and extraction in all state aquifers by 2040, to stabilize the water table at levels that won’t cause undesirable results such as land subsidence and dried-out domestic wells.

But with the dry conditions and the surface water skyrocketing in price, when available at all, nut tree investors faced a stark choice: drill or die. Instead of a slow glide path to sustainability, as the groundwater law envisioned, a get-it-while-you-can race to the bottom of the aquifer broke out. From 2014 through August 2022, at least 70 wells have been drilled on land now owned or managed by the biggest institutional investors in California nuts, including Gladstone, Hancock and TIAA. The majority of those wells descend at least 1,000 feet underground—twice the median depth of all the state’s farming wells drilled in the same period. The wells on investor-owned land typically deploy wider-diameter pipes and are capable of extracting three times more water, on average, than other agricultural wells, according to the data available on state well-completion reports. Several investors say their well-drilling binge doesn’t matter because of pumping reductions mandated by California’s new groundwater rules. They say they’ve also taken steps to minimize their impact by installing more efficient irrigation systems, fallowing some of their farmland and recharging aquifers when excess surface water is available.

The big investors long knew the day of reckoning would come, say consultants and farm managers who worked with them. After the groundwater law passed, Hancock commissioned a report starkly warning that Hancock-managed almond and pistachio orchards would be tens of thousands of acre-feet short of water when the sustainability plans were fully implemented.

By then, however, most institutional investors assumed the investments would have long ago paid off, says David Orth, who ran the Central Valley’s Westlands Water District in the 1990s. “Even when we told institutional clients you’ll be short of water in 15 years, they said, ‘OK, but I can make a lot of money in 10,’ ” Orth says.

That was Hancock’s message to its investors last year, according to documents obtained by Bloomberg Green under Florida’s public-records law. In a presentation to Florida pension fund managers in February 2022, the company warned that it expects California’s groundwater regulations to limit well-water production in Tulare County by 75% by 2040. As a result, Hancock said it anticipates fallowing two-thirds of an 1,800-acre pistachio farm in the county by then. Still, “strong current cash flows”—the farm’s income earned a 10% return in 2021—“are expected to help mitigate this risk,” Hancock reassured investors.

Felicia Marcus, the state’s top water regulator from 2012 through 2019, says she recalls local farmers complaining that outside investors were out of control. Ripping out seasonal food crops to plant wall-to-wall almonds and vineyards amid historic drought was, well, nuts, they told her. “All of a sudden you had this influx of landowners who weren’t farmers and didn’t know or care about the history of land use here,” says Marcus, chair of the California State Water Resources Control Board at the time. “Behind the scenes, farmers were saying, ‘Someone’s got to stop them.’ ”

Hancock learned its lesson the hard way. In 2010 it paid $78 million for a 12,000-acre cattle ranch called Triangle T in Madera County, 70 miles northwest of Fresno. The ranch had rights to only a small amount of surface water, however, which meant Hancock would have to pump more than 30 million gallons of groundwater a day to irrigate the vast plantation.

In 2011, Hancock punched at least five wells more than 900 feet into Triangle T’s deep aquifer and the surrounding area. It carpeted the pastureland with 11,000 acres of nut saplings, destroying a 400-acre preserve of native vegetation, says Grover Wickersham, who sold Triangle T to Hancock and whose grandfather founded the ranch. “Permanent crops went from essentially zero to 100%.” A Hancock spokeswoman wrote in an email the company is unaware that a nature preserve was on the property and that it maintains 520 treeless acres for dry-land farming and aquifer recharge during floods.

In 2012 scientists working on restoring the nearby San Joaquin River for the US Bureau of Reclamation discovered that the Sack Dam was sinking several inches a year. The subsidence threatened an irrigation system serving 50,000 acres of farmland. The eventual suspected culprit: Hancock’s deep-water extraction beneath Triangle T. Farmers and irrigation districts on the river’s west side threatened to sue Hancock if it didn’t reduce the pumping.

Averting a lawsuit, the company agreed to throttle its deep pumps and purchase deliveries of surface water from west of the river, where farmers have some of the strongest water rights in California. After the agreement, which cost Hancock parent Manulife higher water bills and lower crop yields, the subsidence rate at the Sack Dam decreased by half. It also provided a model for how at least wealthy investors can adapt. “We’re hitting our goals under the agreement,” says Lucas Avila, Manulife’s senior manager of Triangle T. “Long-term sustainability is near and dear to everybody.”

Across the valley to the east, Hancock and other institutional investors continue to plumb the deep aquifer with little restraint. Near Woodville, construction has begun on an almost $300 million repair of a stretch of the Friant-Kern Canal. State officials say overpumping by farms has caused subsidence along the vital artery, which carries water 152 miles from a Sierra dam above Fresno to Bakersfield. The project’s first phase aims to fix a buckled section where water moves at only 40% of the volume at which it flowed when the canal was built in the 1950s.

In the past 20 years, the 6 miles between Woodville and the Friant-Kern Canal have been transformed into a giant nut plantation, with almost 5,000 acres of trees planted by institutional investors. In 2015, Hancock drilled two wells in the area at least 900 feet deep to water the drought-parched acreage. Four years later, TIAA dropped four wells to an average depth of about 1,100 feet on land it converted to pistachios. Woodville’s two wells, a few miles away, descend up to 600 feet.

“To knowingly go into a region like that and drill deeper wells really tests the limits of corporate ethics,” says Famiglietti, the Arizona State hydrologist, who did some of the earliest research at NASA on overpumping and subsidence in California. “This is coming at us at 100 miles an hour.”

TIAA, in an email from a spokesperson for its farmland subsidiary, Nuveen Natural Capital, said its water use at its Woodville-area farm has become more efficient by its replacement of 14 older wells with five new ones, as well as its installation of drip irrigation systems and its fallowing 60 acres for groundwater recharge. Since 2019, when the orchard was planted, TIAA said it’s deposited more water into the local aquifer than it’s extracted for irrigation of the immature trees, with about half that replenished supply coming just this year. These management practices mark “tangible examples of Nuveen’s commitment to sustainable agriculture,” the company wrote.

Subsidence also poses a serious risk to the California Aqueduct, the 440-mile canal that carries water from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta down the Central Valley’s west side to Los Angeles. From 2013 to 2016, overpumping dropped parts of the concrete structure almost 3 feet, according to the California Department of Water Resources, the canal’s operator. Last summer the 160-mile midsection was dropping 4 inches a year, says John Yarbrough, assistant deputy director of DWR’s State Water Project.

The buckling is expected to cost almost $900 million to fix. Officials blame the problem on the rampant expansion of permanent croplands. “What we are doing is more than we are able to sustain,” Yarbrough says.

Among the most active drillers along the California Aqueduct’s sinking midsection is Canada’s Public Sector Pension Investment Board, known as PSP Investments, the C$230 billion ($168 billion) pension fund of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and other Canadian security services. In 2020, PSP bought 17,000 acres in the San Joaquin Valley, including 11,000 acres of mostly almond trees in western Fresno County purchased for approximately $234 million. Then, in the teeth of the drought, PSP drilled six wells of more than 1,000 feet each on the almond lands. Four of them are located within 1 mile of the sagging aqueduct, on land that sank from 1 inch to 5 inches a year from 2020 through 2022, according to the California Department of Water Resources. A fifth lies within 3 miles of the canal. The wells can extract anywhere from 1,200 gallons to 3,500 gallons of water a minute.

A PSP spokeswoman referred questions to Pomona Farming LLC, its California farm manager. Pomona’s Ceil Howe III says the company’s new wells align with its sustainable farming principles. Pomona is fallowing almost half the acreage it purchased because of water constraints, and its deep wells allow unused surface water, when available, to flow underground into the aquifer. As for subsidence concerns, new pumping restrictions limit groundwater extraction, and, according to maps produced by the local groundwater agency, Pomona’s farmland lies outside the area prone to sinking, he says.

On land beside the city of Coalinga, 50 miles south, a company registered to Allstate Investments LLC called NBInv AF4 LLC bought 4,300 acres of pistachios and other crops in 2019. Land in the vicinity had been sinking for several years. Still, the company drilled two 1,500-foot-plus wells in 2021 and 2022. Last year, Coalinga was forced to buy water on the open market to avoid running out because of reduced surface-water allocations from the state aqueduct. In an email, an Allstate spokesperson wrote that the company’s farm investments emphasize “sustainable water and land usage,” such as pipelines to access surface water, efficient wells, land-fallowing programs and drought-resistant crops including pistachios.

East of Coalinga, the city of Corcoran is the epicenter of the worst subsidence in California. In 2021, Prudential Financial Inc.’s real estate arm paid $26.5 million for a 630-acre pistachio orchard just south of town—in the heart of a cratering area that hydrogeologists have dubbed the Corcoran Bowl. The land has fallen almost 12 feet in places since 2007, damaging infrastructure and crushing domestic wells. Some spots have sunk more than a foot per year.

In March 2022, Prudential drilled a 1,228-foot well into the area’s deep aquifer, capable of extracting 2,400 gallons of water per minute. In an email, a Prudential spokesperson said the farm is helping recharge the aquifer with floodwater this year and has access to surface-water supplies. She added that Prudential purchased the land knowing it was subject to future pumping restrictions to control subsidence under California’s groundwater law.

Imelda Corona’s faucet started gurgling in 2021. She and her husband, both farmworkers, were living in the mobile home near Woodville where they raised their three kids. In 2019, TIAA drilled one of its four wells in the area not far from Corona’s home. TIAA’s well extended 1,070 feet into the deep aquifer. Corona’s descended 150 feet and went dry less than two years later.

Her husband filled small tanks at a nearby farm with water just clean enough for bathing and rinsing their sweat-drenched clothes, but not safe to drink. He paid $2 a gallon for purified water from a roadside stand. After eight months without water, their landlord kicked them out. The couple moved into another trailer with a deeper well and a $500 monthly rent hike. They also have to pay as much as $500 a month for electricity to power the deeper well. “Hopefully the country and the world does something to stop this crisis,” says Corona, 57.

UBS Group AG leases a 675-acre pistachio orchard to tenant farmers next to Lanare (population 500), one of the many farmworker hamlets relegated to the Central Valley’s dusty byways. From her front window across the road, Carmen Hernandez, 72, has watched for 27 years as the fields of cotton, onions and wheat were ripped out. Now there’s a wall of pistachio trees. Last May, as the local water table was plunging, UBS drilled a 900-foot well on the site to augment surface irrigation during drought. “Pistachio yields have exceeded our expectations,” says Erik Roget, who manages California properties for UBS Farmland Investors LLC.

Lanare’s much shallower wells are contaminated and undrinkable. The yellowish liquid that dribbled out of Hernandez’s kitchen tap last fall smelled like rotten eggs and left a brown stain on everything it touched, she says. Hernandez is surprised to learn that the world’s biggest private bank is involved with the orchard across the street, through a company called Olympic Sun LLC. “We need a solution,” she says. Roget declined to comment on Lanare’s water problems, but UBS said in an email that its tenant farmers are expecting ample surface water this year and less groundwater pumping.

A half-hour south of Woodville, the historic community of Allensworth is caught in a vise between a 7,000-acre pistachio farm tilled by Hancock and 4,600 acres of almonds, pistachios and pomegranates owned by Gladstone Land, the publicly traded REIT. Allensworth, founded as an intentional Black community in 1908 by Colonel Allen Allensworth, an escaped slave who served in the Union Army during the Civil War, was among the first towns in the US to be financed, built and governed by African Americans.

Its 177 households, now almost all Latino, drink mostly bottled water because Allensworth’s wells are contaminated with arsenic. Since 2019, Hancock has drilled four wells within 3 miles of the town’s well field, each at least 1,200 feet deep. Allensworth’s well, built in 1984, goes down 250 feet. Two Black families still farm in the community, barely. Ralph Pierro II, 39, grows vegetables on land acquired by his grandfather, who picked cotton at large plantations in the area. Over the years, Pierro watched Hancock’s enormous pistachio orchard rise next door and could make out its new well cisterns through the young trees a few years ago. But he never knew who owned the land.

In March, when a levee failed north of Allensworth, 25 residents worked through the night filling sandbags to save the town. They desperately needed tractors to help plug the levee, but Hancock, which farms about 10 square miles just south of town, didn’t reach out, says Kayode Kadara, 69, a longtime community leader. Nor did Hancock notify Allensworth when it drilled the four deep wells near the town’s water supply, he says. “We never heard from them in drought or flood.” Manulife’s spokeswoman wrote in an email that the company’s employees “live, breathe and work in these communities and are also experiencing challenges with levee breaches.” The company is allowing floodwaters onto its land in other places and assisting communities in need “whenever possible,” she wrote.

To the north of Woodville, past TIAA’s almond and pistachio lands and its 450 acres of walnuts near the city of Exeter, the Friant-Kern Canal flows past a small farmworker community called Tooleville. Surrounded on three sides by citrus orchards, Tooleville’s two wells produced barely a trickle last summer, usually during the evening or early morning, if its 300 or so residents were lucky.

At the end of a block of small houses, only 20 feet from the canal, a 37-year-old woman lives in a mobile home with her husband and six kids. A pair of stray dogs, a decaying wheelchair and a rusty barbecue occupied the front yard on a hot day last fall. She wouldn’t give her full name but called herself Maria. She emigrated from Oaxaca, Mexico, with her parents at age 5 and grew up in Tooleville. Her husband is a roofer, but they pick cherries, grapes and peaches when his work slows down.

Even when her tap dribbled enough water to fill a jug, it took an hour, came out brown and tasted like bleach, she says. A nonprofit agency brought 25 gallons of drinking water every two weeks, which ran out in five or six days. The family filled jugs from the sink for bathing and flushing the trailer’s single toilet. The kids took jug baths when they could. Maria bathed her 2-month-old baby every few days, if there was water. Dirty dishes stacked up in the dry sink for days.

“The toilet was the nastiest,” she says. They tried to bucket-flush every day, but that wasn’t possible. When it grew unbearable, they flushed with drinking water or carried jugs home from her uncle’s house.

Beyond a chain-link fence next to her trailer, water rushes south in the canal, swollen by the heavy rains, headed for almond and pistachio trees tilled by many of the biggest institutional investors on the planet. Maria says she’s never thought about why water flows next door to a million acres of farmland, yet her baby bathed in brown water and the family couldn’t flush their toilet for days.

“That’s for them,” she says, gesturing to the canal, “not for us.”