Land is spiritual, land is ideological, and we cannot afford to give it away for the economic benefits of the investor, argues Professor Sam Lwanga Lunyiigo

Contextualizing customary land registration in Uganda

by Prof. Sam Lwanga Lunyiigo

Introduction

The land crises and large scale land grabs affecting many African countries today stem from historical and colonial mistakes whose problems remain. The systems, policies and laws that are being pushed to “register” and “formalise” land ownership do not put into consideration the cultural and historical aspects that govern land in many countries on the continent. In this article, Professor Sam Lwanga Lunyiigo asks pertinent questions about the push and implications of customary land registration in Uganda.

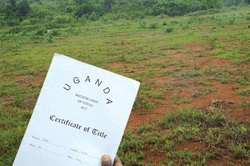

Uganda is inexorably moving towards a single land tenure system of freehold where all land in the country will be privatized and be freely sold and bought. But customary land cannot be registered and titled and remain customary. In most of the work done on customary land registration and titling, I have not seen the engagement of those who know what customary land tenure is. Customary land varies from one community to the other, and there is no codification of customary law yet. So, in this area, a lot of work remains to be done.

Behind all tenure systems recognized in the constitution of Uganda (customary, freehold, leasehold, and mailo land) is the desire for development. There is a feeling out there that if all land can be put on the market, the investors – the guys with the money bags – would come and develop Uganda. The prevailing claim is that the complexities of acquiring land are preventing development and keeping most Ugandans in poverty.

Peasant production is always defined as subsistence. But it is the peasants who grow food that feeds them and the rest, and for over a hundred years, peasants grew the cotton and coffee, which sustained governments. Imagine a landless and rudderless peasantry seeking food from government! The COVID-19 experience has demonstrated quite clearly that Government cannot feed the people. And if we do not step back and think hard again, this single-spine land tenure system we are fervently pursuing will lead us to this spectre of a landless peasantry waiting to be fed.

Since land is the key resource for the majority of Ugandans, the people concerned should be consulted about the registration and titling of their land through a referendum in good faith, without manipulation.

There have been attempts to open all of Uganda to investment. There was a proposal to open up land for investment in Acholi. The Acholi perceived this proposal as a scheme to grab their land by non-Acholis. In his commentary “This land is not yet for sale”, Opiyo Oloya, a prominent New vision columnist, interpreted the war in Acholi as a deliberate action to drive the Acholi off their land, place them in protected camps, break their collective will to survive and take away their land(1). Oloya, in the same article, refers to some non-Acholi Ugandan vultures waiting to grab the land. With regard to Buganda Okello-Okello said: “who holds the best large farms in Buganda? Who owns land in Mubende, Rakai, Mpigi and parts of Masaka? Are they Baganda?”(2)

Apollo Milton Obote was catapulted into politics by the land question in Lango. In 1956,(3) Zakaria Mungonya, who was the Minister of Lands in Governor Andrew Cohen’s regime, established privatisation pilot schemes in parts of Kigezi, Ankole, and Bugisu. When he attempted to do the same in Lango, the people there rejected privatisation of land and the registration and titling that goes with it. They invited Obote all the way from Nairobi to come and help them with the peaceful protest they intended to carry out all over Lango.

He arrived a day after the demonstrations and was arrested by the Colonial Administration which accused him of masterminding the protest. After his release, he launched his political career and the rest is history.

One of the ostensible motives behind the move to register and title customary land is the security of tenure which it is supposed to deliver, and the access to credit institutions with mortgageable land titles. But behind all these wonderful intentions is the fact that this registering and titling will create a land market and eventually deliver landlessness to the masses, with dire consequences for the country. Indeed, Civil Society Organizations for Peace in Northern Uganda surmised: “people won’t be landless for as long as they don’t have titles!”(4)

At the moment, there are contradictory messages about registration and titling. On the one hand, the movement from non-registered and non-titled customary land towards registered and titled customary (actually freehold tenure) land with all the possibilities of buying and selling is good and portends phenomenal development. On the other hand, already duly registered and titled mailo land has been construed as the work of the devil! And yet, through this over-one-century registration and titling, Buganda has the most vibrant land market in Uganda.

As a result of this free-for-all land market in Buganda evictions of peasants are rampant and maybe this is where the devil comes in. But are evictions taking place only in the mailo land tenure jurisdiction and not in other land tenure systems in Uganda? I challenge the researchers to find out. And is there a guarantee that customary land once registered and titled there will be no evictions there? If evictions don’t take place, how will land in this jurisdiction be freed for the big investors?

The Busuulu and Envujjo Law of 1928 has been referred to as the Peasants’ Charter (5) which liberated the peasants from uncertain tenure. It secured their tenure. Under that law, evictions were no longer possible as long as the land rents (which were not arduous) were paid to the landlords. Evictions on mailo land are a new phenomenon associated with the nouveau riche who have sprung up in Uganda over the last thirty years or so to drive the peasants from their land. It is this lot and the foreign land grabbers which promise heaven and deliver hell to the peasants whom they routinely evict in the name of development. And whose development is this which is rendering the peasants landless?

Before colonisation, all polities that were forged into Uganda had what we call a customary tenure system where land was held in trust by the leaders of the clans and bigger political entities for all the people. For example, in Buganda, there was the king who was also the Ssabattaka, the Chief Land Trustee, and below him, there was the Abataka, who were the clan Land Trustees. These leaders catered for the land needs of all where they had user–rights in a system where land was neither bought nor sold but was passed on from generation to generation without too much conflict. And it may be interesting to add that in a typical African community, the dead, the living, and the unborn, are all part of that community. If such a community is also the owner of the land, it would be impossible to identify the seller, and yet there was always progress in those communities without the land being sold or bought.

There is a tendency to allude to “revolutions” in other climes and then construct “revolutions” here drawing from those other experiences. Hence, we talk casually about the fourth industrial revolution as if that revolution belongs to us. Do we hope to make a quantum jump to land on our feet from no industrial revolution at all to the fourth one with nothing in between? We seem to be delusionary in all this to compress our development this way.

In the realm of development, Investment - Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) - rules the roost. The dictums of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, where the opening of markets, privatisation, a fully liberalised foreign exchange regime, are the basic articles of faith. In this regime, land must also be privatised and in Uganda’s case, customary land tenure must be seen as an obstacle to land access. With the registration and titling of customary land, the investors will be in business all over Uganda. This occurrence is supposed to lead to prosperity for all!

We should be sceptical about the above prognosis. Many poor people will lose their land through the land marketplace to the rich and the politically well-connected, who can then sell the same land at a big profit to the foreign investors. Agricultural production may indeed go up but these poor and, now, landless people, will not be the beneficiaries. The rich will get richer and the poor poorer, a situation that will only be resolved by revolution.

Already there is a low-intensity land war going on in Uganda, with a few areas such as Ankole exempted. Why? Because of land grabs from the weak, sometimes with the assistance of our police and army. Peasants are resisting in all sorts of ways. They hack fences, they beat up surveyors, they sometimes kill land grabbers and bona-fide owners, they enter titled land by force, and women in Acholi went bare-breasted to frighten investors off their land. In the future, as the poor become increasingly landless, the landed estates will need a big land army to protect the estates. And this will eventually become untenable.

Buliisa is a very interesting example of what may happen in other parts of Uganda where customary land tenure prevails at the movement. Muhereza, on land in Buliisa, notes: “once they wrested land out of customary control, it was easy for outsiders to purchase it and change its tenure and land use status” (6). Hon. Stephen Mukitale told the 8th parliament in October 2011 that from 2004, the ownership of land in Buliisa began shifting to new landowners as if there were no indigenous communities prior to the oil discovery. He also revealed that all land on which the oil wells were situated had been taken over by claimants who, even before the oil companies could locate the wells, had with 100 percent precision located the sites where oil is situated even before the community (indigenous) came to learn about it (7).

Ddungu observes that “so long as cattle keepers don’t possess dominant social power, grazing provides a weaker customary claim to land than agriculture. Conversely, when cattle keepers have dominant social power, they gain a stronger claim to land than the cultivators” (8). For centuries, the Bahima moved their cattle in the savannah (cattle) corridor all the way from Bukanga to Nyabushozi in Ankole, to Kabula, Mawogola, Singo, Bulemeezi, and Buruli (in Buganda). Bahima were nomadic pastoralists not constrained by borders or boundaries. For them where pastures were, that was their land(9). In the savannah corridor, there were also cultivators who are sedentary and have a more developed sense of belonging to a certain territory. It is these people (cultivators) with a more developed sense of the patria who have lost out to the “Balaalo”. For many years, the Balaalo have attempted to extend the realm of their operations. They indeed bought land in Buliisa (it is not clear who sold this customary land to them). They have also extended their activities to the North of Uganda and even some parts of the East. In 2012, there was an operation conducted by the Government to force them out of Buliisa because this had become an Oil Country and President Museveni has now given them two months to leave the North. If all the land in the North was open to market forces, they would have probably extended their activities there without any hustle at all and this may happen when the registering and titling of customary land opens the land market for them there. And this is what the Northerners are resisting.

If investors take land that Metha, Mandvani, and Mukwano have, then the whole land area of Uganda would be owned by only two thousand landowners. And as you know, there is no ceiling to the amount of land one individual or organization can have. At the moment we have a fill-the-earth population policy and because of this policy, we have one of the highest annual growth rates in the world (3.7%). It is estimated that at this rate the population of Uganda will top 100 Million people by 2050 a mere 28 years from now. So given the neo-liberal economic dispensation that reigns in Uganda, most people will be rendered landless in due course. I do not see any rapid solid industrialisation in Uganda in the near future. At the moment we have set our sights on oil production but will the oil industry lift all the boats? There are many countries that have produced oil for a long time in Africa but with a stinking poverty still around. Will Uganda be an exception to the general misery associated with oil production in Africa?

So, the way forward is for Ugandans to stick to agriculture and to their small farms on which productivity should be increased. Giving away land to the big guys from within and without will not benefit the majority of Ugandans and as we all know ‘king sugar’ leaves a trail of poverty and misery wherever it reigns. As we noted at the beginning of this discourse, land cannot be registered and titled and remain customary. This registered and titled land will definitely be put on the market in distress sales. And after this, the Boda Boda economy will spread all over the country and that will be the end of us.

Land is spiritual, land is ideological, and we cannot afford to give it away for the economic benefits of the investor. Those who teach patriotism in this country should emphasize, in their lectures, the love of people from which the love of country stems.

Uganda should not rush land reforms such as the registration and titling of customary land which will definitely lead to the landlessness of the many as they sell their titles to the rich few Ugandans and non-Ugandans. This now freehold land dispensation that is the aim of the proposed registration and titling reforms may in due course also be declared the work of the devil. So, be warned.

And will property rights, as guaranteed in our constitution, be respected? The Balaalo held titles to the land in Buliisa but became victims of land expropriation “by powerful forces unleashed by a very vicious process of capitalistic accumulation that had nothing to do with the form of production in the countryside”(9). So, unless property rights can be strengthened and enforced, the security of tenure we are looking for by registering and titling customary land will be an exercise in futility. Registration and titling of customary land will only lubricate the gravy train of the land mafia.

Before we rush the customary land reforms, let us consult those concerned. And the questions to ask them should be: Do they feel tenure insecurity with the present customary land arrangements? Secondly; will the registration and titling of their land deliver tenure security to them? After all, the politicians always claim to work in the interest of the people, so let them ask the people what they want.

Endnotes

1. Opiyo Oloya: The New Vision 19/11/1997

2. Okello –Okello: The New Vision 20/05/1998

3. Obote. AM: Milton Obote Telling His Own Story- J.K Kiwanuka message

30/10/2021

4. Civil Society Organizations for Peace in Northern Uganda. Quoted in Mahmood Mamdani; “The Contemporary Ugandan Discourse on Customary Tenure: Some Theoretical Considerations” MISR Working Paper No.13, January 2013.

5. Lwanga- Lunyiigo. S. The Strggle for Land in Buganda p.126

6. Muhereza F.E. “The December 2010 ‘Balaalo’ Evictions from Buliisa District and Challenges of Agrarian Transformation in Uganda”. MISR Working Paper No.17 January 2015.

7. Ibid p.15

8. Ddungu .E. “The Other Side of Land Issues in Buganda”, P.4.

9. Muhereza .F.E. “The December 2010 ‘Balaalo’ Eviction in Buliisa”, p.29.

REFERENCES

Banjwa. A. “Land for Development? Neoliberal Restructuring and Dynamics of Land Reforms in Uganda”. U.p 2021.

Buganda Government. The Busuulu and Envojjo Law 1928

Buganda Government. Reports of the Lukiiko, 1929-33.

Ddungu, E. “The Other Side of Land Issues in the Buganda Pastoral Crisis and the Squatter Movement in Sembabule District”. Center Basic Research, Kampala, Working Paper No.11

Landnet. Customary Land Registry: Resource Book, 2021

Lwanga-Lunyingo S. “Land Legislation and its Implications in the Transformation of Rural Buganda” U.p 1976.

Lwanga -Lunyingo S. The Struggle for Land Buganda, 1888-2005. Wavah Books Ltd, 2013 Edition.

Mamdani. M. “The Contemporary Uganda Discourse on Customary Tenure: Some Theoretical Considerations”. MISR Working Paper No. 13, 2013.

Mamdani. M. Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Kampala: Foundation Publishers, 1996.

Magamba. J. T. Principles of Land Law. Kampala: Fountain Publishers, 2002.

Nabudere. D.W. Imperialism and Revolution in Uganda. Dar-es-salaam: Tanzania Publishing House, 1980.

Nyeko. B. “The Land Question in Swaziland”. Makerere University History Seminar 1976

Muhereza, F.E. “The December 2010 Balaalo’ Evictions from Buliisa District and the Challenges of Agrarian Transformation in Uganda”. MISR Working Paper No.17, 2015.

Uganda Government. The Land Reform Decree No. 3 1975. Entebbe: Government Printer 1977.

Uganda Government. The Constitution of the Republic of Uganda 1995. Entebbe: Government Printer, Entebbe 1998.

Uganda Government. Issue Paper for the National Land Policy (Ministry of Water Land and Environment) Government Printer, Entebbe, 2004.