The Gecko Project and Mongabay | 27 March 2018

How a series of shady deals turned a chunk of Borneo into a sea of oil palm

How a series of shady deals turned a chunk of Borneo into a sea of oil palm

In the leadup to the release of the second installment of Indonesia for Sale, our series examining the corruption behind Indonesia’s deforestation and land-rights crisis, we are republishing the first article in the series, “The Palm Oil Fiefdom.”

This is the fourth part of that article. The first part described a secret deal between the son of Darwan Ali, head of Indonesia’s Seruyan district, and Arif Rachmat, CEO of one of Indonesia’s largest palm oil companies. The second part gave Darwan’s backstory. The third part chronicled Seruyan’s plantation boom. The story can be read in full here.

Indonesia for Sale is co-produced with The Gecko Project, an initiative of the UK-based investigations house Earthsight.

One day in early 2007, a car rolled up outside the home of Marianto Sumarto, the sawmill owner who had helped Darwan Ali get elected. He lived in Kuala Pembuang, a small coastal town that serves as Seruyan’s capital. Marianto recognized the man behind the wheel as a government official, as he rolled down the window to hand over a bundle of papers.

“Take a look at these — there are some issues,” the man said flatly, before driving off.

When Marianto examined the dossier, he found copies of plantation permits Darwan had given to a handful of companies, with a list of directors and company addresses. He immediately recognized the names of some of Darwan’s relatives. Among the addresses, he noted the Kuala Pembuang home of Darwan’s brother.

“I don’t know why he brought me that data,” Marianto told us earlier this year, sitting outside the same house where he had met the whistleblower. “Maybe he cared about Seruyan and wanted to right the ship. Maybe he felt disappointed with how things were going and thought I’d be brave enough to do something about it.”

A migrant from the island of Java, Marianto had arrived in Kalimantan in 1985, joining a friend’s shipping company before switching over to a Malaysian-run timber outfit. He learned on the fly, eventually striking out on his own as an “illegal logger,” as he put it.

When Seruyan formed, Marianto became head of the PDIP party within the new district, at the same time that Darwan was leading the party in neighboring East Kotawaringin. He joined his campaign to become bupati, in 2003, and his brother-in-law became Darwan’s first deputy. But by the time he met the whistleblower, Marianto had soured on Darwan’s rule. He felt he had betrayed the hope that Seruyan would be developed for the benefit of its people. The plantations he had allowed to flood in were having the opposite effect. “That’s what I saw,” Marianto told us. “Maybe I’m the most critical person in this district.”

Wiry and tall, Marianto had a bald head, a raspy voice and a grin that curled upward. When we met, two of his fingers were wrapped in gauze; he had damaged them in a car accident a few days earlier and lost both fingernails. His nickname, Codot — meaning “bat” — was a relic from his days in an amateur rock band in the 1980s. “I know just about everyone in Seruyan,” he declared. “And everyone in Seruyan knows of me.”

A few days after the leak, Marianto and a friend made the four-hour drive to Sampit, to check out a collection of other addresses in the documents. He recognized the first as the home of Darwan’s son Ahmad Ruswandi. They had held campaign meetings there in the run-up to his selection as bupati. Once or twice Marianto had stayed the night. He knew the next one too. It belonged to Darwan’s tailor, who had made their PDIP party shirts.

“The thing is, our country is a corrupt country,” Marianto told us. “A lot of public officials, they didn’t want to bring Seruyan to life. They just wanted to suck it dry.”

The Gecko Project and Mongabay pieced together the story behind Darwan’s licensing spree based on stock exchange filings, government permit databases and company deeds. More information and testimony were provided by Marianto, and a local activist named Nordin Abah, who separately investigated Darwan around the same time as Marianto. We corroborated our findings in interviews with people involved in several of the companies.

The picture that emerges is an elaborate and coordinated scheme to establish shell companies in the names of Darwan’s relatives and cronies, endow them each with licenses for thousands of hectares of land, and then sell them on to some of the region’s biggest conglomerates. Those involved stood to profit to the tune of hundreds of thousands, possibly millions of dollars. If the plan was carried through to completion, it would transform almost the entire southern stretch of the district, below the hilly interior, into one giant oil palm plantation. If Darwan had his way it would be possible drive 75 kilometers east to west and 220 kilometers south to north through a sea of palm.

The scheme involved a cast of more than 20 people who appeared as directors or shareholders in the shell companies. They included members of Darwan’s family, associates from his time as head of a building contractors association, members of his election campaign team, and at least one person who said his name was used as a front.

Darwan’s wife, Nina Rosita, was a shareholder in one. His daughter Iswanti, who would go on to serve as a provincial politician herself, was a director and shareholder in one, a shareholder in a second and director of a third. His daughter Rohana was also a director. His son Ruswandi got a more prominent role, as director of several companies and a shareholder in at least one more. His older brother Darlen had two companies, his younger brother Darwis one. It stretched into his extended family, through Darwan’s nephew and the husband of his niece.

In total, we identified 18 companies that connected to Darwan. Three were incorporated several years before he became bupati. That shows that his interest in large-scale oil palm predated his political career, but that it had stalled: The companies remained inactive until after he assumed office. Two more were formed in 2004, a year into his reign, and then in early 2005 the real flurry of activity began.

Five companies cropped up in a two-day window in late January; another appeared two weeks later. We were able to determine the directors for all of the companies, and the shareholders for all but six.

Almost all of the companies involved at least one of Darwan’s family as a shareholder. His name did not appear on any of them, but Marianto came to the view that he was coordinating the scheme. “They’re like pawns on a chessboard,” he said. “Darwan moves the pieces.”

***

Most of the names were used sparingly. But some cropped up more often than others, and these would provide important clues as to how the scheme functioned. The first was Vino Oktaviano, who was named as a shareholder in three companies set up on the same day, and a director in one.

Nordin Abah, the local activist who carried out his own investigation of Darwan, happened to know Vino well; they sent their children to the same school and sometimes met for coffee. In the wake of the scandal around BEST Group and the national park, Nordin sought out the names behind Darwan’s permit spree. When he found Vino’s name, he challenged him over it. Vino told Nordin that Darwan had used his name, and that he had no actual role in the companies.

“He thought it was normal, that nothing would come of it,” Nordin told us at the Palangkaraya office of his NGO, Save Our Borneo. “He just didn’t want to take any responsibility for it.”

Vino worked as a building contractor, obtaining jobs from Darwan’s administration, and was a nephew of Darwan’s wife. The name of his boss, a confidante of Darwan’s from his days in a trade association, also appeared in company documents.

“You’re going to go to jail Vino, if this thing blows up,” Nordin recalled telling him. “They made me do it, Din.” Vino replied. “I was tricked.”

Where Marianto was a political insider, a mover and shaker in the logging game who soured on the man he once considered an ally, Nordin was a campaigner who hounded the palm oil companies ravaging Seruyan. He also had strong connections to and within the district. His uncle had served as the regional secretary, the highest position in its civil service. On Darwan’s trail, he set about tapping his own relatives in the bureaucracy for leads. He had managed to uncover most of the names involved, noting like Marianto that many of the addresses to which the companies were registered were either duds or owned by the bupati and his family.

Nordin observed that a plantation company would need to operate a factory to mill the fruit, and Vino “couldn’t even run a tofu factory.” He was adamant that other people had been used in the same way. “You might be a teacher, you might be a journalist, you might be a contractor — there’s no way someone like that can get a permit for a plantation,” Nordin explained. “You don’t know how to develop an oil palm company. And you don’t have the money. It’s just for selling. The story is, I use your name to make a permit to sell to someone else.”

The name Ambrin M Yusuf appeared as director of one of the companies. Nordin identified him as a confidante of Darwan from their time in the East Kotawaringin builders association. We tracked him down to his house in Kuala Pembuang, where he had recently returned after serving a jail term for his role as a bag man delivering cash in a local bribery scandal.

He admitted to being a political ally of Darwan, and said that intermediaries had asked him to put his name to the company. But he claimed, implausibly, that he had turned them down, and that the person named in the documents was another man with the same name. He nevertheless admitted that it was “normal” for a bupati to give permits to a family member.

Yusuf and Vino’s stories suggested that cronies were being used as fronts, potentially to keep someone else’s name — the true beneficiary — off company documents. Nordin and Marianto believed that other people whose names appeared were more complicit. They both pointed to a man named Khaeruddin Hamdat as a central figure.

Khaeruddin appeared as director of three of the companies, though never a shareholder. Marianto, Nordin and others identified him as Darwan’s “adjutant.” It is a term commonly used in Indonesia for the person who serves variously as the advisor, right-hand man and fixer for important politicians. Known as Daeng, an affectionate term for a man from his home island of Sulawesi, Khaeruddin was only in his mid-30s by the time the companies were formed. Nordin described him variously as the “boss in Jakarta” and Darwan’s gatekeeper, meeting with palm oil executives in a posh hotel in the capital. (Khaeruddin declined to comment for this article.)

“Because Darwan has to protect himself,” Nordin said. “No way he uses his own name to cut a deal.”

Most of those involved in the scheme proved to be elusive or declined to comment when they got a sense of what we were asking questions about. But one of the few people we knew for sure where to find was Hamidhan Ijuh Biring. He had been jailed for yet another corruption scandal, and we tracked him down to a prison on a main boulevard in Palangkaraya, the provincial capital.

Hamidhan’s name appeared as a director and shareholder of one of the 18 companies. He was also married to Darwan’s niece. He told us that he had set up the company and received a license from Darwan, but lacked the capital to develop a plantation. Darwan encouraged him to sell the company to a political ally in Jakarta who also served as director of an existing plantation company in the district. After the deal went through, Hamidhan received one portion of the payment but the second, he later discovered, went directly to Darwan. “It turns out Darwan was inside, telling him, ‘No need to pay Hamidhan’,” he said bitterly.

Before his relationship with Darwan soured, Hamidhan was an insider, campaigning with him ahead of his 2008 reelection bid. He corroborated Nordin and Marianto’s claim that Khaeruddin Hamdat served as Darwan’s adjutant. He said that whenever he met the bupati, Khaeruddin was there with him.

***

The sequence of events after the shell companies were formed tells us two things. Firstly, that the intent was never for the founders to develop the plantations themselves. Between December 2004 and May 2005, Darwan gave 16 of the companies permits for plantations. By the end of 2005, at least nine of them had been sold on to major palm oil firms for hundreds of thousands of dollars. It seems implausible that a series of interconnected people, in many cases family members, would concurrently form companies only to decide that they lacked the capacity to run them. The sole explanation is that they were set up to be sold, endowed with assets from Darwan.

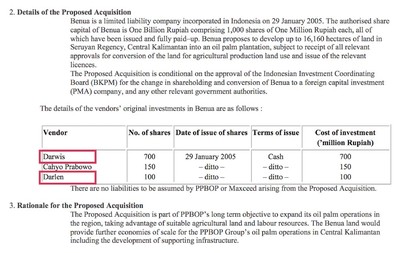

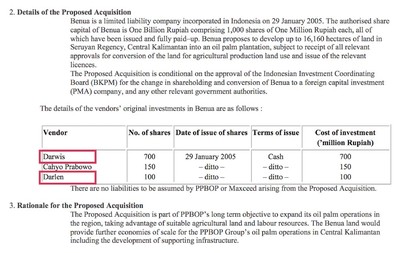

Darwan Ali provided licenses to 18 companies owned by his family and cronies. Almost all of them were sold to Triputra Agro Persada and to the Kuok Group’s oil palm arm, PPB Oil Palms, which was later merged with Wilmar International. Source: Bursa Malaysia, Ditjen AHU, Nordin Abah, Marianto Sumarto and others.

Secondly, it tells us there was a strong degree of coordination in the ways they were both formed and sold. Most of the companies were established within a small window of time, many of them just days apart. Several were also sold within a small period of time some months later.

Eight of the shell companies were bought by the Kuoks in late 2005. Darwan’s family and cronies would eventually derive just under a million dollars from the deals with the Malaysian billionaires. In the scheme of things, it was a pittance, a fraction of what the Kuoks would earn from the plantations if they were developed. But in these deals, the shareholders linked to Darwan also kept a 5 percent stake in each of the companies, which could make each of them multimillionaires in their own right.

The Kuok Group’s PPB Oil Palms announces a deal to buy 95 percent of a company owned by Darwan Ali’s brothers and a Seruyan politician, in October 2005. The company had been incorporated nine months earlier. Source: Malaysian stock exchange.

The evidence Nordin obtained of the connection between Darwan’s family and the companies sold to the Kuoks was first outed in an international NGO’s report, in June 2007. It was just two weeks before two of the Kuok family companies were merged under the name Wilmar International, forming what is now possibly the world’s largest palm oil firm. Wilmar was already attracting heat for a litany of illegalities and social and environmental abuses across its plantations. The same year, a consortium of NGOs filed a complaint with the World Bank ombudsman, providing evidence, later upheld, that the institution had breached its own safeguards by financing the controversial firm.

Though the allegations regarding Darwan’s licenses only received a brief mention in the NGO report, the whiff of a corruption scandal may have proved too much. In an email responding to questions for this article, Wilmar told us that it had decided to mothball the companies issued by Darwan after engaging with NGOs. It declined to mention when the decision was made, and continued to list the companies in its annual reports as late as 2010.

Triputra Agro Persada, presided over by the young Arif Rachmat, bought seven companies from the bupati’s family. (Triputra declined several requests for an interview, directed to Arif Rachmat, although they did respond to some questions via email.) Four of these companies were later mothballed, but the other three, which were developed, linked directly to Darwan’s son Ruswandi. By the end of 2007, two of these companies had already begun clearing vast tracts of forest, peat soil and farmland. Triputra would emerge as one of the worst oil palm companies in Seruyan for people and the environment, in a crowded field.

***

Marianto was certain that Darwan had betrayed his constituents. By the time he met the whistleblower in early 2007, the plantation boom was fully underway, yet the average Seruyan resident remained worse off than in the era of logging. Now, the only option for many farmers was to earn a pitiful wage as a laborer on one of the estates. They were losing their farmland, the destruction of forests deprived them of food and other resources, and fishing grew increasingly difficult in polluted waters. Above all, the promise that the mega-plantations would be accompanied by smallholdings for the farmers, thereby cutting them in on the spoils, went undelivered.

Marianto placed the blame for the problems that were emerging at Darwan’s door. The bupati had the power to revoke licenses as well as issue them; if he was motivated to do so, surely he could force the companies to deliver for Seruyan’s people? The leak confirmed that his motivations lay elsewhere.

Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission, the KPK, born after the fall of Suharto, was emerging as a new force in the fight against graft by public officials. In June 2007, as Indonesia passed Malaysia to become the world’s top palm oil producer, Marianto packaged up his findings and traveled to Jakarta to deliver them to the agency in person.

As 2007 drew to a close, delegates from around the world arrived on the Indonesian island of Bali for the 13th annual UN climate change conference. The fate of the earth’s forests was firmly on the agenda. But in the high rises of Jakarta a different game was afoot. Four days before the UN summit began, as Darwan Ali prepared to campaign for his first direct election, his son Ruswandi stepped into the Kadin Tower for his meeting with Arif Rachmat, to cut another deal with Triputra.

***

After Suharto resigned there was optimism that the grand larceny of his regime would recede. It was hoped that the rapid decentralization of authority would shift accountability for political decisions close to the people affected by them. But by 2008, the year of the first direct vote for bupati of Seruyan, it was increasingly clear that corruption had simply been moved down through the system.

In a forthcoming book entitled Democracy for Sale, political scientists Ward Berenschot and Edward Aspinall write that Indonesia’s districts came to be dominated by “a netherworld of personalized political relationships and networks, secretive deal making, trading of favors, corruption, and a host of other informal and shadowy practices.”

Elections were a cornerstone of this game. They had become hugely expensive affairs, with the cost proportionate to the amount of power over lucrative projects or natural resources the winner could dole out to supporters. For bupatis governing land- and forest-rich districts, they routinely ran into the millions of dollars. Berenschot, Aspinall and other academics who have studied Indonesian elections over the past two decades have identified a uniform, systematic process by which candidates spend their money.

First, they pay off officials in their political party to ensure their selection as a candidate. Next, they recruit an extensive group of political activists and influential figures to join their “success team.” Then they provide cash for the success team to buy up the support of local powerbrokers — village chiefs, religious leaders and the heads of sports clubs who enjoy extensive influence in some places. These individuals in turn solicit the support of people within their own spheres of influence.

Candidates organize expensive rallies and concerts, paying for popular singers to perform and handing out free meals. Finally, they engage in what is generally referred to as a “dawn attack,” organizing dozens of supporters to hit the streets and knock on doors, handing out money directly to voters to solicit their endorsements. This, Berenschot told us, is the costliest part for candidates. He estimated the price of running for bupati at between $1.2 million to $6 million.

The funds come from local businesspeople and contractors, in the expectation of rewards if the candidate is successful. “After the election, it is payback time, and campaign donors and workers can expect to be rewarded by winning candidates with jobs, contracts, credit, projects and other benefits,” write Berenschot and Aspinall. But they also note that incumbents start from a position of advantage, having built up a “war chest — typically by engaging in various forms of corruption,” for the next election. “The exchange of favors and material benefits at every stage of the electoral cycle is so pervasive that it is apt to think of democracy in Indonesia as being for sale.”

By his own admission, Hamidhan Ijuh Biring, the husband of Darwan’s niece who obtained a license from the bupati, played such a role in the 2008 campaign. At the time, Hamidhan told us, he already believed that Darwan had ripped him off. But he still thought he could be rewarded if the incumbent retained his seat, and he was in on the winning ticket.

Hamidhan told us he contributed $50,000 to Darwan’s campaign ahead of the election. He understood he was joining a cast of characters who had benefited personally from the bupati’s patronage: building contractors to whom Darwan had handed lucrative projects without public bidding, which was then legal; plantation bosses who could instruct their workers, many of them migrants from other islands, to vote for the incumbent. In the dawn attack, he said, cash worth $10 to $25 would be attached to the back of instant noodle packets and distributed to voters.

In February 2008, Darwan won the election and resumed his position as bupati of Seruyan for a second five-year term. To celebrate, his brother Darlen organized a concert near the lake, featuring the singer Rhoma Irama, known as the King of Dangdut. No one had stood a chance of making a meaningful challenge to Darwan given the spending advantage provided by his hold on the bupati’s chair. He prevailed despite a brewing storm, as resentment of the plantations grew. The consequences of the land deals he presided over would soon become fully apparent to the people of his district.

Read the entire the story here. And then follow Mongabay and The Gecko Project on Facebook (here and here in English; here and here in Indonesian) for updates on Indonesia for Sale. You can also visit The Gecko Project’s own site, in English or Indonesian. Read the article introducing the series here.