[caption id="attachment_9586" align="aligncenter" width="554" caption="Nasser Mohamed Al Hajri, Chairman of Hassad Food. (Photo: Qatar Today)"] [/caption]

[/caption]

by Joyce Lee

The UN World Food Summit in Rome last month convened diplomats, policymakers, scientists and NGOs to address the growing gap between the world’s nutritional needs and its current agricultural output. Save for Italy’s Prime Minister – who didn’t have very far to travel – none of the G8 leaders attended, a conspicuous absence denoting just how far down food security sits on their national agendas. Quite the opposite for HH the Emir Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, who couldn’t have made Qatar’s stance any clearer.

“The misery of poverty and famine affecting over 1.1 billion people should not be considered as a mere food security issue, but rather a threat to the world security; more dangerous and closer to reality than the threat of nuclear weapons,” said the Emir. The matter of food security, he added, is 'about the future of freedom and peace'.

Shortly afterwards, HH The Emir announced the creation of Qatar’s National Food Security Programme (QNFSP), a taskforce of 14 organisations dedicated to reducing the Gulf nation’s reliance on agricultural imports. Born from a directive from HH The Heir Apparent Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, QNFSP is exploring solar power, water desalination, and agricultural technologies like hydroponics as potential long-term solutions, according to Chairman Fahad Al Attiyah.

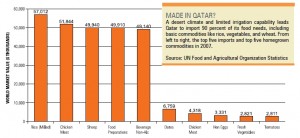

It was less than two years ago that global food prices skyrocketed, inciting panic buying and hoarding as nations shored up their own food security by instituting export bans. Suddenly food production became dire for Qatar, where 90 percent of food is imported, tying the country to the unpredictable metrics of international trade markets.

Enter Hassad Food, a private arm of the Qatar Investment Authority sovereign wealth fund and member organisation of QNFSP. Last year, it was tasked with securing the nation’s food supply while garnering financial returns.

“What initiated Hassad is the change of climate, the need of food, the increase in world population, and the trend to divert from food to biofuels because of oil prices,” says Nasser Mohamed Al Hajri, Chairman, Hassad Food. For food-poor, oil-rich Qatar, the issue is not only about striving for self-sufficiency, but profits as well.

Many peers, like the Saudi Arabian Savola Group or Al Qudra in the UAE, have already struck large-scale land lease deals abroad.

“On the one hand, you’ve got rich countries with the resource of funds to invest and on the other hand, you’ve got poor countries with land and water resources,” says David Hallam, Deputy Director of the Trade and Market Division at the UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). “Potentially, both sides could gain.”

This acquisition trend, nicknamed ‘land-grabbing’ by the media, has been accused of compromising the smallholders who hold customary land rights, and possibly diverting food away from underfed population.

Al Attiyah maintains, “Qatar is in a unique position, and cannot only lease land internationally, but is dedicated to transmitting knowledge, practices and technologies to the local communities in which it invests." The country is addressing food security on two fronts – innovating domestic production to wean the country off a dependence on imports, and investing in agribusinesses abroad to generate food supply and profits.

Growing tomatoes in the desert

Out of Qatar’s 11,253 sq km, there is not a single tract of naturally arable land, according to FAO maps. In fact, the entire peninsula is classified as ‘dry land with low production potential’, though some distinction is made between the barren southern areas and the shrubland of the north. Despite low precipitation and nextto- zero topographical relief, Hassad Food has invested $9.6 million on food production within Qatar.

“Now we will have greenhouses and scattered farms, either owned by Hassad or with guaranteed intake by the company,” Al Hajri says. At the end of January 2009, Hassad absorbed the food production company Hassad Barwa from Barwa Real Estate, which previously launched the 14 million sq m Arakiya farm project. The operation uses treated sewage water to grow fodder for animals, offsetting imported feed.

“Animal breeders used to buy it at 40 or 60 riyals per piece, and now they are capable of buying it at 20 to 25 riyals,” Al Hajri says, adding that, two more farms will begin operating when the government approves fieldwater supply.

These irrigation systems allow Qatar to produce a few thousand tonnes of commodities each year, like dates, tomatoes and soon cut flowers. Last month, Hassad Food signed a $68.5 million deal with Oman’s A’Saffa Poultry, a move that will fulfill 20 percent of Qatar’s chicken meat and egg demands. But the State has its eye on strategic land abroad, where the mass of basic food imports, like wheat, rice, and sheep meat, originate.

Seeking greener pastures

Hassad Food plans to invest all over the world. “Latin America, Asia, you name it,” says Al Hajri, “Where we invest, we make profit. If Qatar is in need of that production, Hassad has the pleasure to sell to Qatar at no special rate.” The company’s strategy is to target regional operators in host countries, and either establish a joint production venture with them or acquire them wholly. It has already partnered with the Sudanese government to establish Hassad Sudan with a $100 million investment for 20,000 hectares and the potential to expand to $1 billion for 225,000 hectares. The wheat and sorghum farm’s operator will come from the private sector – either an Australian or Saudi Arabian company.

“Land is such a sensitive subject,” says Ruth Meinzen-Dick, Senior Research Fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute. “It’s in the interest of the investors to have stability, and when local people are not treated well or ecology is not given due attention, then you’re going to have problems: Either productivity is not as high as expected or you get longterm degradation and unrest.” Hence the strategy away from land acquisition in developing countries, which often need education, healthcare, and policing as much as Qatar needs food.

But the story is different in Latin America, where leasing tracts of land is on the table for Hassad Argentina. Hassad Turkey, a $100 million investment, will lease land for livestock, wheat, and barley. And agricultural output could be seen as soon as next year, said Al Hajri, from Hassad Food’s largest project thus far, a $400 million investment in Australia.

A win-win situation?

Foreign investment is not intrinsically good or bad, but a hefty injection of funds can be disastrous for citizens if left unregulated. “Ethics in agriculture has been starved of investment over many decades,” says Hallam. “That’s why there’s been a kind of international call for some kind of code of conduct to regulate these investments, to make sure that the interests of developing countries are taken into account.” The FAO is currently working with the World Bank and others to measure political will for such guidelines. “Everybody is a stakeholder,” says Devlin Kuyek, Director of NGO GRAIN. “It’s a food system, and we all have to eat.”

Kuyek believes that profit-seeking investors will negatively impact global food prices and the developing world’s access to food, an outcome Qatar has publicly criticised. Hassad Food has even signed agreements with eight NGOs, including Qatar Charity, which the chairman promises will be in Sudan ensuring any social impact is positive. Like others, the country is demonstrating waning faith in the world market’s ability to accomplish its fundamental raison d’etre of feeding people. While the need for insulation from an unstable world system is understandable, Qatar should heed the Emir’s message that food security involves more than a country’s appetite.