Globe and Mail | 19 August 2009

U.S.-based fund snaps up 1,100-acre patch in Quebec and says it plans to seek more properties

STEVE LADURANTAYE

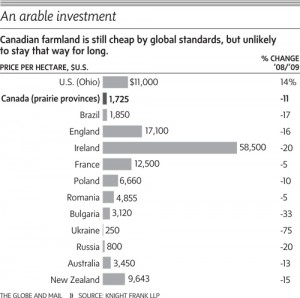

INVESTMENT REPORTER The renowned cranberry harvest in southern Quebec has long attracted tourists to the picturesque region. But the cranberry bogs sprinkled throughout the countryside near Victoriaville attracted a different type of sightseer earlier this summer - a billion-dollar, U.S.-based agriculture fund hungry for cheap Canadian farmland. Attracted by the Canada's low political risk and fertile fields, Hancock Agricultural Investment Group, a Boston-based unit of Toronto's Manulife Financial Corp., decided its first Canadian purchase would be an 1,100-acre (450-hectare) patch of land that it called "one of the most highly productive properties in the industry." The company will not disclose how much it paid, or even the exact location of the farm. But president Jeff Conrad said the company is in Canada to stay, and the fund plans to seek more land. "A lot of people get uncomfortable because they don't know us and they don't know how we operate," he said. "We aren't in this to flip properties, and we're not fast money. Our clients are long-term, institutional firms - pension funds - and they have a place in their asset allocation for farmland." According to a report by London-based Knight Frank LLP, Canadian farmers can expect a flurry of international interest in the coming months as investors bet that low commodity prices will rebound as the world struggles to meet its need for food. Canadian farmland is still cheap by global standards, but unlikely to stay that way for long. Large global funds are increasingly drawn to Canada and Australia as they seek agricultural investments, with a hectare of arable land in the Canadian Prairies worth about $1,725 (U.S.), according to data collected at the beginning of the year, said Knight Frank's head of rural property research, Andrew Shirley. Comparable land in England goes for $17,100; in Australia, it's $3,450. While land can be purchased for less in developing countries, there are often complications that make ownership difficult.

"Large investors want to buy in Canada because the government isn't going to come take your land away on a whim," he said. "There's also infrastructure, so once you've harvested your crops, there are good roads to get to market. If your combine breaks, someone can fix it. This is an attractive proposition."

There is a gigantic asterisk beside the $1,725 figure for Canadian land. Foreign ownership is restricted in the Prairies and, up until 2002, only residents of Saskatchewan could actually own land in the province. This has kept prices depressed, and opened the door for Canadian-only funds to snap up assets at low prices.

Agcapita Partners LP and Assiniboia Capital Corp. each operate funds that purchase large swaths of prairie land, with an initial investment averaging $10,000. Only Canadians may invest.

Both point to the same data when pitching their products - farmland around the world has appreciated at a rate 2 per cent higher than inflation since the 1950s. At a time when investors are looking at 50-per-cent losses on their stocks, it can be an attractive proposition.

"When we started out five years ago, people thought we were nuts," said Stephen Johnston, president of Agcapita, which has about $100-million under management. "Canada has the lowest prices for land, and the most productive land of any G8 country. This is real property that kicks off cash and isn't going anywhere."

The market could open up - Saskatchewan Agriculture Minister Bob Bjornerud has suggested he's open to changing the ownership rules to attract fresh capital to the Prairies. It's a conversation that is still in its infancy, but likely to get louder as aging farmers look to cash out and move on.

In the meantime, large funds will continue to look to provinces such as Ontario and Quebec for investments. There are no specific rules in those provinces, although the Investment Canada Act does contain a passage that allows the federal government to overrule a transaction it sees as a threat to the national interest.

"As the agricultural industry continues to globalize and trade barriers continue to fall, we believe the United States, Australia and Canada, and other large and efficient producers, stand to benefit," said Hancock's Mr. Conrad. "It's a big country, and most of the deals you see will still be between farmers. But that doesn't mean there aren't opportunities for other players."

While land can be purchased for less in developing countries, there are often complications that make ownership difficult.

"Large investors want to buy in Canada because the government isn't going to come take your land away on a whim," he said. "There's also infrastructure, so once you've harvested your crops, there are good roads to get to market. If your combine breaks, someone can fix it. This is an attractive proposition."

There is a gigantic asterisk beside the $1,725 figure for Canadian land. Foreign ownership is restricted in the Prairies and, up until 2002, only residents of Saskatchewan could actually own land in the province. This has kept prices depressed, and opened the door for Canadian-only funds to snap up assets at low prices.

Agcapita Partners LP and Assiniboia Capital Corp. each operate funds that purchase large swaths of prairie land, with an initial investment averaging $10,000. Only Canadians may invest.

Both point to the same data when pitching their products - farmland around the world has appreciated at a rate 2 per cent higher than inflation since the 1950s. At a time when investors are looking at 50-per-cent losses on their stocks, it can be an attractive proposition.

"When we started out five years ago, people thought we were nuts," said Stephen Johnston, president of Agcapita, which has about $100-million under management. "Canada has the lowest prices for land, and the most productive land of any G8 country. This is real property that kicks off cash and isn't going anywhere."

The market could open up - Saskatchewan Agriculture Minister Bob Bjornerud has suggested he's open to changing the ownership rules to attract fresh capital to the Prairies. It's a conversation that is still in its infancy, but likely to get louder as aging farmers look to cash out and move on.

In the meantime, large funds will continue to look to provinces such as Ontario and Quebec for investments. There are no specific rules in those provinces, although the Investment Canada Act does contain a passage that allows the federal government to overrule a transaction it sees as a threat to the national interest.

"As the agricultural industry continues to globalize and trade barriers continue to fall, we believe the United States, Australia and Canada, and other large and efficient producers, stand to benefit," said Hancock's Mr. Conrad. "It's a big country, and most of the deals you see will still be between farmers. But that doesn't mean there aren't opportunities for other players."