And how do European development banks monitor the environmental and social impact of their more than 2,000 investments, valued at billions of euros, in biodiversity and climate hotspots such as the Congo Basin?

PHC considers the waste episode closed. It indicates that it paid the corresponding fine to the Provincial Directorate of Collection in April, showing the receipt for an amount equivalent to 28,000 euros. It also denies having made direct payments to any official.

The European creditors knew about the infringement. They also knew that the authorities had initially tried to impose abusive fines on PHC, in the company’s own words. What the German (DEG), Belgian (BIO), Dutch (FMO) and British (CDC Group) development banks did not know was the fate of the 20 tons of expired phytosanitary, toxic, dangerous and radioactive products.

InfoCongo and El Paìs asked these institutions how they monitor compliance with the Environmental and Social Action Plan, on which the debt reduction depends. “We do regular monitoring and dialogue with the client on its implementation,” the German DEG said by email on behalf of the consortium, noting that they take the issue of toxic waste very seriously and will look into it. According to the FMO website, the banks also commission audits by local consultants and visit plantations every two years.

On this occasion, dialogue with the client was not enough. “We at PHC did not feel the need to indicate to the development finance institutions (DFIs) that the continuation of the process [waste dumping] had been carried out in compliance with national laws,” the company noted.

In 2019, the Dutch FMO wondered “what happens when the company is truly committed to implementing the Environmental and Social Action Plan, but lacks the budget because [palm oil] prices are at rock bottom.” But informing local communities does not cost money. Nor does signposting a hazardous product landfill.

Cases like PHC’s show how difficult it is for investors to control high-risk projects in countries with weak institutions and governance. “The PHC case shows that DFIs are not serious at all about holding the companies they invest in to account. They made no serious effort to address the many abuses and violations that were brought to their attention, including the legacy land issues that were long known to them, and have not even taken their own grievance mechanisms seriously,”says GRAIN researcher Devlin Kuyek from Montreal. Countries where the funders themselves are not present to monitor, directly, the performance of clients to whom they have injected millions of euros. The example of PHC also highlights what is known as “distancing from accountability”, an idea that is beginning to sound and worry in forums such as the European Parliament.

The concept is simple: the more complex transnational investment networks become, the more intermediaries and jurisdictions there are, the harder it is to determine who is responsible for violations on the ground. Far away, in tropical forests on the banks of the Congo, the Sarawak and the Orinoco; hours away by plane, boat and motorcycle cab from the Paseo de La Castellana, the carpeted offices of The Hague and New York’s Fifth Avenue.

In 2008, a study proved the hitherto urban legend of six degrees of separation: anyone on the planet is connected to anyone else through an average of six intermediaries. The same is true of global financial webs. Without proper firewalls, well-meaning investors can end up backing projects far removed from their principles: from rainforest deforestation to labor exploitation to tax optimization for the benefit of obscure global elites. The girls who work picking cassava leaves at the Congolese plantation dump have little idea who is at the other end of the investment chain.

For starters, there are the founders of the private equity firms that acquired PHC in 2020: Walé Adeosun, a former Obama advisor for US-Africa trade who manages capital for ultra-wealthy clients; Kalaa Mpinga, a Congolese gold and diamond tycoon, nephew of a Kabila oil minister; and Larry Seruma who ran a BBVA and Vega hedge fund and, like so many others, started his career with Bernard Madoff, the mastermind of the biggest Ponzi scheme in history.

At the same time, the cataract of funds connected to PHC has been fed by the capital of large American universities such as Northwestern, Washington in Saint Louis and Michigan. It has also been nourished at certain times by the Gates Foundation and South African pension funds, as reflected in the tax returns of investors consulted by InfoCongo, EL PAÍS and the Oakland Institute.

Spain, France and the United States invested in the plantations through the African Agriculture Fund (AAF), and countries such as Switzerland and Sweden entered through the Emerging Africa Infrastructure Fund (EAIF), to whose piggy bank contribute the African Development Bank, the British bank Standard Chartered and the German multinational financial services company Allianz. Responsibilities are being diluted as intermediaries increase. Who is accountable?

The development banks call their fund managers. They pass the buck to the company’s management. The executive team blames the local authorities, who blame the company. And it’s back to square one. And in the case of PHC, there is yet another twist.

The private equity firms are squaring off in courts in Delaware, New York, Toronto and Kinshasa over ownership of the company, which they value at €88 million. Hundreds of pages of court documents examined by InfoCongo and EL PAÍS describe the maneuvers of these firms: mutual loans at 17.5% interest, accusations of resurrecting tax avoidance schemes at PHC and investments in mysterious agricultural enterprises. E-mails between the creditors and the funds suggest: The corporate web behind PHC is so convoluted, even the development banks are confused.

Public Funds, Opaque Finances

Civil society is a crucial investment watchdog. However, “European development finance institutions (DFIs) are incredibly opaque: only three of them publish their sub-investments,” explains a knowledgeable source. “They compete with each other and with commercial banks, so the priority of those working there is not always development.”

This is corroborated by a recent report by the Development Finance Institutions Transparency Initiative (DFI Transparency Initiative), part of the global Publish What You Finance campaign: “The lack of transparency [on sub-investments] means that it is almost impossible to understand their impact on development. (…) This is unacceptable, especially when these institutions use public money and, in some cases, official development assistance.”

NGOs, legislators, citizens and taxpayers find it difficult to follow the activities of development banks in their countries. The same is true for affected communities. “It is critical that financial institutions improve the provision of disaggregated information on each of their investments,” says the Initiative’s expert Paul James.

Countries’ climate, biodiversity and human rights commitments – such as those announced at COP26 – depend on the ability to follow the money from the pockets of international investors and consumers to places like Tshopo. Especially as land in Southeast Asia becomes saturated and agribusiness begins to look for alternatives in the pristine forests of Central Africa.

Agribusiness to Conquer Africa

The planet conserves three great tropical forests: the Amazon, Southeast Asia and the Congo Basin. But the best preserved is the third. Its forests, the size of about seven Cameroon feed rivers in the sky: colossal flows of water vapor that emanate from the leaves and act as a natural thermostat, regulating the climate of the region and the world.

“However, these areas of vital importance for climate and biodiversity are also the most conducive lands for the expansion of crops such as oil palm, which is native to Central and West Africa,” says Denis Sonwa, a scientist at the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

Central Africa’s forests are smaller than those of the Amazon, but they absorb more carbon dioxide. They are also home to the world’s largest tropical peatland, a carbon bomb the size of England. Peatlands are wetlands with a thick layer of organic matter that occupy only 3% of the earth’s surface, but store 20% of the world’s soil carbon.

In Asia, millions of hectares of peatlands have already disappeared in the face of palm encroachment and, in addition to the effects of deforestation, there are the effects of pollution and population growth around macro plantations. Indonesia and Malaysia produce 90% of the oil used in cosmetics, chocolate, animal feed and detergents. But rising global consumption, land scarcity in Asia and economic momentum in Africa point to the beginning of a new palm oil boom in the Congo Basin.

In 2009, PHC declared that it would stop deforestation and limit replanting, but there are another half hundred industrial oil palm plantations in the region. Several of them have expansion plans. Others, such as Luxembourg’s Socfin and Singapore’s Olam, are accused of land grabbing and clearing community forests. Socfin has benefited from funds from France (Proparco) and the World Bank, and Olam from the African Development Bank.

In the last 30 years, the area devoted to palm oil in the Congo Basin and five other producing countries in the region has increased by 40%. And there are still 280 million hectares suitable for cultivation, most of them in the DRC, Cameroon and the Republic of Congo. “Without intervention, production increases will come from expansion, rather than intensification, of crops (…) possibly at the expense of the forest,” warns CIFOR.

What Now?

In Lokutu, they don’t know where to bury their dead. This year, Congolese police arrested a local man for trying to bury a body in a soccer field. “The houses are under the palm trees; the latrines are under the palm trees; even our graves are under the palm trees,” explains neighbor Joseph Meia.

In the green bowels of the DRC, communities live off the forest. “But here everything is imported. In the forest surrounding the plantations, there is no more game and even firewood for cooking is a problem,” says Meia.

The PHC gobbled up ancestral lands that today correspond to seven local entities. In Bolesa, there are 23 villages that are islands in an ocean of palm trees. To reach the forest, you have to cross this sea. “In February, my brother, Blaise Mokwe, went out to get branches to make a broom,” says Eddy Baitita. “Because he was carrying a machete, the guards thought he wanted to steal palm fruits and killed him.” He was 33 years old.

Manu Efolalofa, 20, disappeared the same month after being arrested by plantation guards. His mother, Ogeno Losana, has nine other mouths to feed: “I tried to grow a vegetable garden in the forest, and the local communities chased me away. I moved to another plot, and the company put up.

I moved to another plot, and the company clapped its hands. Now I sell carafes of oil to survive.” Losana hopes that the company will compensate her one day, at least by employing one of her children.

According to EL PAÍS, the company has calculated that the people of Lokutu steal the equivalent of 10,000 tons of oil a year in palm fruit. PHC Lokutu’s current production is around 17,000 tons.

“If they paid people well, they would not be forced to steal fruit and fuel,” says one employee. Despite his 30 years of seniority, he earns only €1.4 a day, and his family subsists below the extreme poverty line. He has never seen the chocolate cream or the moisturizing lotions produced from the fruits he harvests. None of his three children go to school.

In theory, the company could become a role model. “Rejuvenating existing plantations and improving their yields, rather than expanding them, is a good way to respond to the demand for palm oil and reduce deforestation,” says Rocio Diaz Chavez, the deputy director in Africa of the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), a global benchmark in environmental research and policy. “But paying someone $30 a month is not aid; it’s neocolonialism.”

Voracity. Opacity. Lack of control. Diluted responsibilities. When William H. Lever founded Huileries du Congo Belge in 1911, the man known as the Napoleon of soap aspired to create a clean business. Yet what PHC has ended up offering are 100 years of lessons about the failures of agricultural, financial and governance systems in a globalized world.

Mistakes that investors, governments, and companies will have to make amends for the future of the forests and the people’s dignity.

Credits:

Story supported by the Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN) of the Pulitzer Center and produced in collaboration with Kuang Keng Kuek Ser, Jelter Meers, Kevin Nfor and Madeleine Ngeunga from InfoCongo. Originally published in Spanish in the Planeta Futuro section of El País.

InfoCongo Editorial Coordinator: David Akana

Investigations: Madeleine Ngeunga/Infocongo, Glòria Pallarès/El Paìs, Jelter Meers/Rainforest Investigations Network

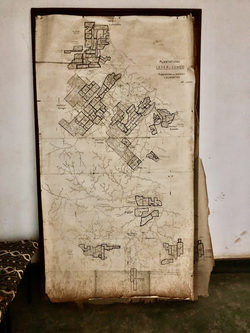

Maps: Kuang Keng Kuek Ser/Rainforest Investigations Network

Data analysis: Kevin Nfor

Translations: Fabrice Wekak

InfoCongo Tech team: Stefano Wrobleski, Jason Mandabrandja, Jimmy Glorial Mandabrandja