The conference of Berlin, as illustrated in 1884, which established the rules for the conquest and partition of Africa. (Image: Wikicommons)

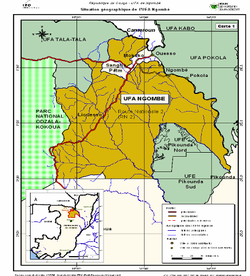

The Sangha Region in the Republic of Congo

There is a serious risk that conservation and extractive industries will exert full control over tropical forests by implementing so-called ‘nature-based solutions.’ (1) These include large-scale carbon offset projects and the creation of more protected areas, as well as the continuation of supposed ‘sustainable’ logging and industrial tree plantations. Nevertheless, it is important to understand the implications that such territorial control can have on forest-dependent communities.

The heavily forested Sangha region in the north of the Republic of Congo is one example of how territories can end up entirely under the control of conservation and extractive industries. Three concessions occupy almost the whole region: one held by the palm oil company Eco-Oil Energie SA, one by the Odzala-Kokoua National Park and one by the logging company Industrie Forestiere d'Ouesso - IFO (see map).

While climate chaos would indicate that the alleged ‘nature-based solutions’ are more like ‘fantasies’ than anything else, the three companies in the Congo are mainly concerned about their businesses and competing among themselves, both in terms of the green propaganda they disseminate, as well as around the promises they make to grassroots communities. What is kept hidden, however, is the fervently unequal, racist and patriarchal nature of such concessions, which have their origins in colonial times. The three companies have deployed armed guards and/or local police against the local inhabitants of these forest areas to prevent them using their ancestral lands.

This article describes certain aspects that expose those behind each of the companies and their perception about grassroots communities.

Eco-Oil Energie

Oil palm grows naturally in the forests of the Sangha region. Archaeological sites show there is a longstanding tradition of the planting of oil palms by forest-dependent communities, especially women.

The radically different model of industrial oil palm plantations has its roots in colonial times, when the Compagnie Française du Haut et du Bas Congo (CFHBC) was granted a concession of 7.5 million hectares, covering an area with the combined size of Belgium and the Netherlands, to start producing palm oil on an industrial scale. Following independence, in 1983 the company was renamed Sangha Palm, a State-owned company with at the time a plantation area of 33,000 hectares. In 1990, and due to a financial crisis then taking place, the Sangha Palm oil factory was closed and the plantations were abandoned by the company. (2)

After Sangha Palm left, peasant farmers, particularly the women for whom oil palm is an essential part of their culture, continued harvesting palm fruits from the Sangha Palm plantation. They produced palm oil through artisanal methods and sold the oil at local markets, providing them with an important source of income. A peasant woman stated at that time: “(..) we have always extracted palm oil. With the money we make from selling our oil we buy medicine and clothes for our children.” (3)

But all of this came to an end when Eco-Oil Energie was formed in 2013, after Malaysian investors negotiated an agreement with the Congolese government to take over the control of the Sangha Palm oil plantations. They also took control over thousands of hectares of plantations in the Cuvette region that belonged to another State-owned oil palm company, the Régie Nationale des Palmeraies du Congo (RNPC).

Eco-Oil Energie SA Malaysia received a 25-year concession over 50,000 hectares, and announced it would recover what it called ‘abandoned’ plantations, ignoring the importance of this territory for the livelihoods and welfare of local people. By 2015, the project had received around USD 89 million from its Malaysian investors. The Gabon-based BGFI Bank and the Togo-based Ecobank also invested in the enterprise. The company project included investing in the plantations as well as in producing palm oil, margarine and biodiesel. At the time it was announced that the biodiesel was to supply both the domestic and export markets. The company also announced its goal to increase its plantation area to 300,000 hectares in the future. (4).

Oil palm plantations are one of the major causes of deforestation worldwide. Eco-Oil Energie’s director claimed in 2015 that the company only replants so-called ‘abandoned’ plantations while conserving the remaining forest (5). However, a critical report of consultants who visited an Eco-Oil concession area in 2016, reported deforestation, illegal practices and conflicts with communities, among others, in the Cuvette region. (6)

Besides the Malaysian investors, the President and CEO of Eco-Oil Energie, Claude Wilfred Etoka, has greatly profited from the company’s activities. One of the owners of Eco-Oil Energie is a Swiss-registered company called Eco Oil Energie Sarl, which in turn is owned by a Cyprus-registered company called the WEC Group. (7) Etoka is the only shareholder of Eco-Oil Energie Sarl.

Etoka is a controversial figure to say the least, as his name has been linked to numerous illegal practices. The coalition “Opening Central Africa” has alleged that Etoka is the “cash man” for President Sassou’s money laundering schemes (8). According to research from Global Witness and Mediapart, Etoka intermediated with international investors for the privatisation of the two former State oil palm companies, Sangha Palm and RNPC, to create Eco-Oil Energie. But that was not his only move, he has done the same for another 45 State companies, building up a huge business empire in the Republic of Congo that covers the oil extraction, agro-industry and manufacturing sectors. (9)

Some investment deals signed by Etoka on behalf of Eco-Oil Energie in recent years indicate that the company is in a process to expand its activities and production area beyond the palm oil business. For example, Eco-Oil signed an agreement with an Israeli company in 2018 to invest in mango and orange cultivation for juice production (10) and another in 2019 with Camaco, a Chinese investor, to invest in manufacturing agricultural equipment (11).

Industrie Forestière d´Ouesso (IFO)

The company Industrie Forestière d´Ouesso (IFO) has a 1.16 million hectares logging concession in the north of the Republic of Congo. IFO is owned by the Swiss-based Interholco company, which took the concession over from a State company called SCBO in 1999. SCBO was founded in 1985. Interholco is a subsidiary of the Danzer company, an Austria-based hardwood enterprise.

The Danzer company was founded in 1932 by the German Karl Danzer and profited from the tropical timber imports and trade business. In 1962, Interholco was founded in Switzerland, which took over the marketing of African timber for mainly European markets. Danzer’s office was moved from Switzerland to Austria in 2015, among others, for tax benefits. (12)

IFO’s logging operations are certified by FSC and claim to be “the largest certified continuous forest area in tropical regions”. (13) Although the FSC certification system has proven to be no guarantee for consumers of tropical timber products, particularly regarding whether the certified area will be conserved and social well-being of communities ensured inside the concession area (14). For its part, the Danzer group managed to lose its FSC certificate in 2011. This was due to FSC´s decision to dissociate from the company after Greenpeace exposed the activities of Danzer subsidiary SIFORCO in DRC, including systematic illegal logging and involvement in human rights violations. (15)

This decision also exposed WWF, as Danzer was a leading partner in that organisation´s “Global Forest and Trade network” initiative. (16) In 2014, however, WWF celebrated in a press release that IFO had received its FSC-certificate back again, only urging the company “to enforce strict anti-poaching rules” (17).

These rules are probably related to the fact that the company reports about 16,000 people living inside the concession area, including indigenous communities. The company states that it has approximately 40 so-called eco-guards to constantly patrol its area against “illegal harvesting, poaching, bushmeat trade, and irreversible change” (18).

In 2015, IFO, Eco-Oil Energie, WWF and other partners were involved in a project approved by the Global Environmental Facility (GEF), with funding of more than USD 3 million, with the aim to reinforce the protected areas in the Republic of Congo. In 2018, the NGO Survival International on behalf of the indigenous Baka people filed a complaint against GEF and the other proponents involved in the project. The Baka people claimed they were forcefully evicted from their lands. (19) A team of investigators from the UN Development Programme (UNDP), gathered evidence that the Baka people had for years been subjected to violence and physical abuse from the guards, including beatings, criminalisation and illegal imprisonment, the burning and destruction of property, rape, and humiliation by forcing women to take off their clothes, among other atrocities. (20) UNDP eventually suspended the project. This shows what such patrolling can mean for inhabitants of forest areas that companies like IFO claim to protect.

The Odzala-Kokoua National Park

The creation of the Park in 1935 appropriated the biggest forest area in the same region with 1.35 million hectares. Since 2010, the control of the Park is entirely in the hands of the African Parks Network through a public-private partnership with the Congolese government for a period of 25-years. (21)

The African Parks Network was founded in 2000 and presents itself on its website as a non-profit organisation that manages 19 national parks and protected areas in 11 countries in Africa. It is nevertheless registered as a company in South Africa. The president of the company is His Royal Highness Prince Henry of Wales, a member of the British royal family.

The company controls a total area in Africa of 14.7 million hectares, about half the size of Italy, and it intends to expand even more in order to manage 30 parks by 2030. It highlights carbon capture as one of the potential benefits of its parks, indicating the Network’s interest in selling carbon credits as an additional source of income. In spite of its supposedly non-profit character, the company undertakes business activities in the Odzala-Kokoua National Park, which includes so-called Discovery Camps where tourists can fly in on charter flights from the Congolese capital Brazzaville. However, very few inhabitants of Brazzaville have the possibility to enjoy such luxury tourism. A 4-day Odzala Discovery Camp visit, for example, costs USD 9.960 per person. (22)

Behind the African Parks Network is also a large group of governments, multi-lateral institutions, conservation organisations, family foundations and individuals that fund its conservation business. The partners of the Odzala-Kokoua National Park in the Republic of Congo include conservation groups such as WWF, the Congolese government, and the European Union.

While the Park was founded in 1934, the African Parks Network itself states that “humans have occupied the area for 50,000 years”. The company continues stating that 12,000 people still live around the Park, “yet it is still one of the most biologically diverse and species-rich areas on the planet” (emphasis added). With this affirmation, rather than recognising the inhabitants’ contribution towards keeping the forest standing after all these thousands of years, the company makes clear that in its view, the presence of people is not compatible with the aim of conserving forest; it is despite the communities’ presence that there is still biodiversity left.

The African Parks Network claims to protect the Park “with an enhanced eco-guard team and other law enforcement techniques”, besides investing in “changing human behaviour”. To achieve this objective, the Network receives support from the US Department of State, which “began providing support in 2018 and has committed over US$3 million for ranger uniforms, equipment and training”, as well as “leadership development” to help achieve the “enhanced capacity to disrupt illegal wildlife trade and promote regional stability”. These claims and views on conservation make clear that for this Network and its funders and allies, people living in and around forests are considered a threat and that their conservation business can be run better without them.

At present, other large-scale concessions are being granted in the Republic of Congo in line with the agendas of extractive and conservation industries. However, the interests of countries and companies in the Global North is to continue extracting minerals, timber, palm oil and other products, as well as doing business with conservation, which represents a common and persisting characteristic of these extensive projects.

However, what is left for communities since the days of European colonisation are lands and forest areas they no longer have access to, and whenever they try to enter, they are being confronted with a violent, racist and patriarchal oppression, including now at the hands of so-called ‘eco’-guards.

WRM Secretariat

(1) WRM Bulletin 255, “Nature-Based Solutions”: Concealing a massive land robbery, April 2021

(2) WRM, Oil Palm in Africa. Past, present and future scenarios. 2013

(3) Idem

(4) Farmlandgrab, Eco-Oil Energie investira 350 milliards dans un projet agroalimentaire au Congo, 2015

(5) Eco-Oil Energie SA, 2015

(6) Rapport de Mission Pilote REDD+. Sur la thématique « autorisation de déboisement » pour la consolidation d ́une approche d’observation indépendante des exigences du processus REDD+ en République du Congo, 2016

(7) Wikipedia, Claude Wilfrid Etoka

(8) Opening Central Africa, Christel Palace: High Treason In The Tropics

(9) Global Witness, What lies beneath, 2020

(10) Israel Science Info, Goutte-à-goutte : une fruiterie de 700 Ha au Congo-B irriguée grâce à Rivulis (Israël), 2018

(11) Panapress, Accord de partenariat entre la société congolaise Eco-Oil énergie et la chinoise Camaco, 2019

(12) Danzer Group

(13) Lesprom, Danzer subsidiary IFO renews its FSC certificates for the Republic of the Congo, 2014

(14) See information about FSC on WRM’s website and FSC-Watch

(15) Greenpeace, Danzer feels the bite as the FSC show its teeth, 2013

(16) FSC-Wacth, Another FSC and WWF flagship company in Africa bites the dust as Danzer sells SIFORCO

(17) WWF, Largest forest concession in the Congo Basin receives FSC certification, 2015

(18) Global Compact Network, Sustainable Hardwood – Made in Africa, good for forest, people and planet

(19) UNDP, Social and Environmental Compliance Unit SECU, Integrated and Transboundary Conservation of Biodiversity in the Basins of the Republic of Congo, 2018

(20) The Guardian, Armed ecoguards funded by WWF 'beat up Congo tribespeople', 2020

(21) African Parks

(22) Congo Conservation Company, 2021 rates