25 May 2021

Pollution and green washing Problems around Socfin plantations continue

Civil society groups working with communities affected by the rubber and oil palm plantations of the Socfin group use today's Annual General Meeting of the company to speak out about ongoing problems.

Socfin is a Luxembourg-based conglomerate, 40% owned by the Bolloré group, that has amassed 400,000 hectares of land concessions in 10 countries of Africa and Asia. Key issues arising in the last year include disputes about water pollution and land use, and questions around the company's Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil certification process.

For 2020, Socfin reported a consolidated net profit of about €30 million. The three main holdings of the group - Socfin SA, Socfinaf SA and Socfinasia SA - paid out dividends of €13.7 million. Nearly three-quarters of that (€10.1 million) went to top shareholders Vincent Bolloré and Hubert Fabri or companies controlled by them. In addition, the holdings paid their directors €16.5 million, of which nearly 60% (€9.7 million) went to the Bollore and Fabri families. This comes to a total of about €20 million that was split between the two business partners and their associates. At the same time, the group reports continuous losses in more than half of the countries where it runs plantations.[1]

Pollution in Indonesia

Also in countries where the Socfin plantations do report big profits, the situation of the local people can be quite difficult. Socfindo, with nearly 50,000 hectares of land concessions in Indonesia, made over €36 million in profits last year. In July 2020, representatives of five communities in Aceh filed a complaint [2] with the Environmental Agency of Naga district against three oil palm plantations, one of them being Socfindo, for allegedly polluting the Seumayan River with oil palm processing waste on a repeated basis. This reportedly leads to skin diseases among the villagers. The communities thus urge the authorities to do an environmental audit of the companies and reassess the permits granted to those found responsible for polluting the river. In December 2020, villagers from Gunung Meriah Aceh Singkil district, with the support of 22 local chiefs, demanded that their local authorities release to them a part of Socfindo’s concession area near their villages. The lease expires in 2023 and a spokesperson from Gerak PAS, a local NGO accompanying the community, says that “the villagers don’t want Socfindo’s current lease to be renewed.”

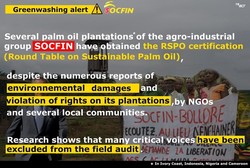

RSPO: Socfin’s greenwash

Socfin has been awarded RSPO certification in Cameroon, Ivory Coast and Nigeria, and the certification process is on-going in other countries, despite well documented and on-going land conflicts in several of these plantations.[3] New research by Milieudefensie[4] indicates that during the certification process in Africa, critical voices, including communities that have land disputes with the company, were not consulted. Several organisations and community members said they were intimidated or manipulated during the consultation process. According to the research, there are issues about the independence of the audits as well. For example, company staff acted as translators during consultation sessions with communities. Samuel Nguiffo, director at the Cameroonian NGO Centre pour l'Environnement et le Développement (CED), explains: “The lack of independence of the audit from the company, the exclusion of critical voices and the fear for backlash when speaking out prevent a meaningful consultation. How can the auditors conclude the company is sustainable based on such a faulty process? The Socfin RSPO certificates are a greenwash exercise.”

Companies like Socfin extract immense profits from the lands and labour of communities in Africa and Asia. Green washing only makes matters worse. We therefore urge Socfin to change its practices immediately.

Signatories:

Pollution and green washing Problems around Socfin plantations continue

Civil society groups working with communities affected by the rubber and oil palm plantations of the Socfin group use today's Annual General Meeting of the company to speak out about ongoing problems.

Socfin is a Luxembourg-based conglomerate, 40% owned by the Bolloré group, that has amassed 400,000 hectares of land concessions in 10 countries of Africa and Asia. Key issues arising in the last year include disputes about water pollution and land use, and questions around the company's Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil certification process.

For 2020, Socfin reported a consolidated net profit of about €30 million. The three main holdings of the group - Socfin SA, Socfinaf SA and Socfinasia SA - paid out dividends of €13.7 million. Nearly three-quarters of that (€10.1 million) went to top shareholders Vincent Bolloré and Hubert Fabri or companies controlled by them. In addition, the holdings paid their directors €16.5 million, of which nearly 60% (€9.7 million) went to the Bollore and Fabri families. This comes to a total of about €20 million that was split between the two business partners and their associates. At the same time, the group reports continuous losses in more than half of the countries where it runs plantations.[1]

Pollution in Indonesia

Also in countries where the Socfin plantations do report big profits, the situation of the local people can be quite difficult. Socfindo, with nearly 50,000 hectares of land concessions in Indonesia, made over €36 million in profits last year. In July 2020, representatives of five communities in Aceh filed a complaint [2] with the Environmental Agency of Naga district against three oil palm plantations, one of them being Socfindo, for allegedly polluting the Seumayan River with oil palm processing waste on a repeated basis. This reportedly leads to skin diseases among the villagers. The communities thus urge the authorities to do an environmental audit of the companies and reassess the permits granted to those found responsible for polluting the river. In December 2020, villagers from Gunung Meriah Aceh Singkil district, with the support of 22 local chiefs, demanded that their local authorities release to them a part of Socfindo’s concession area near their villages. The lease expires in 2023 and a spokesperson from Gerak PAS, a local NGO accompanying the community, says that “the villagers don’t want Socfindo’s current lease to be renewed.”

RSPO: Socfin’s greenwash

Socfin has been awarded RSPO certification in Cameroon, Ivory Coast and Nigeria, and the certification process is on-going in other countries, despite well documented and on-going land conflicts in several of these plantations.[3] New research by Milieudefensie[4] indicates that during the certification process in Africa, critical voices, including communities that have land disputes with the company, were not consulted. Several organisations and community members said they were intimidated or manipulated during the consultation process. According to the research, there are issues about the independence of the audits as well. For example, company staff acted as translators during consultation sessions with communities. Samuel Nguiffo, director at the Cameroonian NGO Centre pour l'Environnement et le Développement (CED), explains: “The lack of independence of the audit from the company, the exclusion of critical voices and the fear for backlash when speaking out prevent a meaningful consultation. How can the auditors conclude the company is sustainable based on such a faulty process? The Socfin RSPO certificates are a greenwash exercise.”

Companies like Socfin extract immense profits from the lands and labour of communities in Africa and Asia. Green washing only makes matters worse. We therefore urge Socfin to change its practices immediately.

Signatories:

|

AFASPA (Association Française d'Amitié et de Solidarité avec les Peuples d'Afrique ; France) Alliance for Rural Democracy (Liberia) |

| BIPA (Bunong Indigenous People Association; Cambodia) |

| Bread for all (Switzerland) |

| Collectif pour la défense des terres malgaches – TANY (Madagascar) |

| Creatives for Justice (Switzerland) |

| FIAN Belgium (Belgium) |

| FIAN Switzerland (Switzerland) |

| GRAIN (Spain) |

| Green Advocates (Liberia) |

| Green Advocates (USA) |

| Green Scenery (Sierra Leone) |

| JUSTICITIZ – ACORN (Liberia) |

| Milieudefensie (Netherlands) |

| Natural Resources Women’s Platform (Liberia) |

| Oakland Institute (USA) |

| RADD (Réseau des Acteurs du Développement Durable ; Cameroon) |

| Rainforest Rescue (Germany) |

| React Transnational (France) |

| SOS Faim (Luxembourg) |

| Synaparcam (Cameroon) |

[1]All calculations were made on the basis of the 2020 annual reports found at http://www.socfin.com.Socfinaf did not distribute dividends for 2020 earnings - we refer to the three holdings as a group nonetheless. For payments to board directors, we assume that each member receives the same amount.

[2]https://www.mongabay.co.id/2020/08/22/sungai-tercemar-limbah-masyarakat-nagan-raya-laporkan-tiga-perusahaan-sawit-ke-dinas-lingkungan-hidup/

[3]Several of these conflicts are summarized and referenced in the report of Milieudefensie (p. 22), see below.

[4]Milieudefensie, «Palm oil certification: not ‘out of the woods’», 2021-03-19; https://en.milieudefensie.nl/news/palm-oil-certification-not-out-of-the-woods.pdf