by GRAIN and Fernando Frank | 3 Mar 2020

The business group Cresud controls 370 thousand hectares in the province of Salta, in the ancestral lands of the Wichi people. There, in the first months of 2020, nine children have died from malnutrition and lack of water. We must not allow agribusiness to keep claiming lives.

For weeks the whole of Argentina has been shaken by a tragedy that is not new, but that has, temporarily, occupied the front covers of the papers for the first time: since the beginning of this year, nine Wichi children have died due to malnutrition and lack of drinking water [1].

In all likelihood, in a few weeks this news will fade into the background, with less significant headlines taking its place. This is an opportune moment, however, to go beyond condemning what is happening, to also think of the root causes and above all formulate and execute policies to stop these tragedies from continuing.

The place where the children are dying is clearly identified: the Santa Victoria Este municipality in the north of Salta province. The threat, however, undoubtedly extends across the whole territory inhabited by the Wichi people.

The Wichi people are an indigenous nation that occupy the Gran Chaco in South America, which spreads across what today is northern Argentina and southern Bolivia. They also historically lived in territories in what is now Paraguay. Historically, the Wichi people were a nomadic, hunter-gatherer nation who converted to a sedentary lifestyle after colonialization.

To identify the causes of the problem we have collected statements from the head of the National Institute of Indigenous Affairs (INAI, acronym in Spanish) Magdalena Odarda when, for the first time in the history of the institution, she visited the area: “The community leaders asked for many things but in particular they asked for water. They have been suffering water shortages for a long time as a result of deforestation and indiscriminate land clearing.” Ms Odarda added, “We recorded each community that needed water. Those who do have wells put the water in drums that are fumigated and are all contaminated by agrochemicals.” INAI is the official body in Argentina responsible for promoting and protecting the rights of indigenous people in the country.

A clear official diagnosis: the expansion of agribusiness in transgenic soya and maize monocultures in the territories has done away with the forest from which these people lived, and which also represented a source of water as part of these ecosystems.

These ecosystems have been destroyed by agribusiness. The province of Salta has one of the highest rates of deforestation of all Argentina: between 2007 and 2017 the province lost more than 750 thousand hectares of forest according to official reports [2]. Together with Santiago del Estero, these two provinces are suffering the greatest loss of forest in Argentina, and also have the greatest rates of deforestation in the world.

In recent days we heard, from the Ministry for the Environment, Juan Cabandié, that the administration of the former minister, Bergman, returned 38 million dollars received as part of a World Bank project that specifically had the objective of ensuring water supply to the communities [3].

The Interamerican Commission of Human Rights decided to intervene after the petition presented by the organisation Naturaleza de Derechos. The State of Argentina must present reports within two weeks on the situation of the following: drinking water, health and food, and measures adopted to find a solution.

Cresud

However, beyond the serious issue of governmental responsibilities, of course there are also key private actors involved in the advancement of agribusiness throughout the region. In this case there is one in particular that can be held to account. This is Cresud, a NASDAQ publicly traded company, property of Eduardo Elsztain. Cresud in turn owns 62% of the IRSA Corporate Group. IRSA is the biggest real estate company in Argentina.

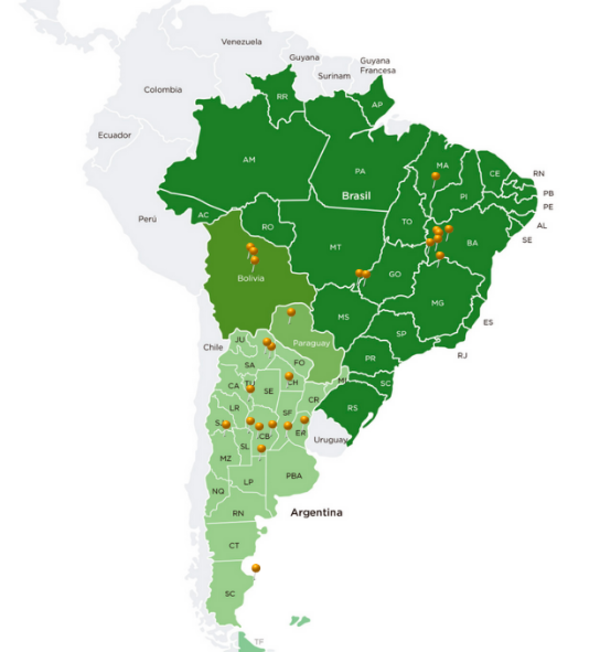

Cresud is proud to state that its portfolio consists of 800 thousand hectares in Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Bolivia [4]. Strikingly, its establishment map shows that just two of such establishments located specifically in the Province of Salta (Anta and Los Pozos) represent 370 thousand hectares of its holdings that are set aside for agriculture and livestock farming (and also as a reserve in Los Pozos). These establishments are located in the same province and region where the terrible events described above are taking place. This makes the company one of the big land grabbers, and without a doubt one of the main entities responsible for the desperate situation the Wichi people currently find themselves in.

The agricultural activities on which the company focuses are essentially maize and soya production (more than 600 thousand tonnes across both crops harvested in 2018), sugar cane production and cattle farming for meat and milk production. The way they present themselves clearly depicts their technological choices: “We believe that an opportunity exists to improve the productivity and long-term value of inexpensive and/or underdeveloped land by investing in modern technologies such as genetically modified and high yield seeds, direct sowing techniques, and machinery.”

As regards animal husbandry, according to a 2018 Greenpeace Report, deforestation in the Argentinian Chaco undertaken by the company exceeded 100,000 hectares, more than double that caused by agriculture [5].

Cresud sets out its business strategy on its webpage [6]. There it explains that in their search for profit, they seek to maximize their return on assets and overall profitability by acquiring agricultural properties having attractive prospects for increased agricultural production, optimizing the yields and productivity by implementing state-of-the-art technologies and agricultural techniques.

At the same time Cresud informs us that it seeks to “Maximize the value of their agricultural real estate assets”, through the application of certain “principles”: the acquisition of underused properties and enhancing their land use that includes: transforming non-productive land into cattle feeding land, transforming cattle feeding land into land suitable for more productive agricultural uses, enhancing the value of agricultural lands by changing their use to more profitable agricultural activities; and reaching the final stage of the real estate development cycle by transforming rural properties into urban areas as the boundaries of urban development continue to extend into rural areas.

In Salta and in other territories, their approach to achieving these objectives has been to buy lands, clear them, incorporate them in the agribusiness activities: transgenics, pesticides and machinery, and additional irrigation using centre-pivot technology.

The business strategy, as they take it upon themselves to explain, includes public trading on the stock exchange and property speculation.

We at GRAIN denounced [7] Eduardo Elsztain back in 2013 as one of the big land grabbers at the global level and shared part of his story: “In the 1990s, George Soros financially supported Elsztain in the buying of an undervalued property in Argentina, through his family company IRSA. The quickly earnt millions and decided to use part of the earnings to acquire Cresud, a real estate company with about 20,000 hectares of farmland. With another significant injection of money by Soros and the public trading on the Buenos Aires stock market, Cresud dramatically expanded its agricultural property. At the end of 1998, it owned 26 properties with a total surface area of 475,098 hectares.”

Doctor Medardo Ávila Vázquez, one of the Group of Physicians for Fumigated Peoples, clearly defines what is happening in an article he wrote for Enredacción. “Argentina is facing a humanitarian crisis that has been hidden because the victims are not seen; they were recently ‘discovered’ when the forests were destroyed. They didn’t even have papers (ID). Five hundred years after destroying America with the biggest genocide in the world’s history, we are now repeating history with the same inhumanity as then. This crisis is structurally rooted, the incorporation of agribusiness production to populated territories is being promoted, with complete disregard for the population” [8].

However, Eduardo Elsztain does not seem to be worried about the consequences of his actions. In recent statements to an Argentinian media outlet he said, “If you go from here [his office] to the convention centre there isn’t a single free parking spot... people think that the country is going through the worst period in its history, but we have just had the biggest grain harvest in the history of Argentina” [9].

The livelihoods of thousands of families on the Gran Chaco are based on the breeding and hunting of animals, the collection of medicinal herbs and foods in the native forest, as they have been been for multiple generations. The only possibility for peasant-indigenous populations to exercise their right to food and health is having access to and control over their territories. If the country continues to leave their best lands captive to agribusiness and speculation, the financial, nutritional and health realities of these people will necessarily be increasingly dire. The logic of record harvests at the expense of ecocide and ethnocide must stop. This is the only route possible to start along the path to a reality in which the lives of the people come before business.

____________

1. Perfil, “Salta: ya son nueve los menores que murieron en lo que va del 2020”, [“Salta: now nine children have died this year”], 21 February 2020 (in Spanish), https://www.perfil.com/noticias/sociedad/salta-ya-murieron-9-menores-2020-infeccion-respiratoria.phtml

2. Ministerio de Ambiente y Dessarrollo Sustentable, Informe Monitoreo de la Superficie de bosque nativo de la República Argentina, 2018, [Ministry for the Environment and Sustainable Development, Native Forest Surface Area in the Republic of Argentina Monitoring Report, 2018] (in Spanish), https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/1.informe_monitoreo_2017_tomo_i1_3_0.pdf

3. ambito.com, “Bergman devolvió u$s38 millones destinados a proveer de agua a los wichís en Salta”, [“Bergman returned US$ 38 million intended to supply water to the Wichis in Salta”], 22 February 2020 (in Spanish), https://www.ambito.com/politica/bergman/bergman-devolvio-us38-millones-destinados-proveer-agua-los-wichis-salta-n5083578

4. Cresud, Regional Agricultural Portfolio, https://www.cresud.com.ar/portfolio.php?lng=en

5. Greenpeace denuncia destrucción del Gran Chaco por frigoríficos locales y supermercados extranjeros, Greenpeace, [Greenpeace denounces the destruction of the Gran Chacho by local slaughterhouses and foreign supermarkets], 3 August 2019 (in Spanish), https://www.greenpeace.org/argentina/issues/bosques/2120/greenpeace-denuncia-destruccion-del-gran-chaco-por-frigorificos-locales-y-supermercados-extranjeros/

6. Cresud, Business Strategy, https://www.cresud.com.ar/compania-nuestra-estrategia-de-negocio_inst.php?lng=en

7- GRAIN, ¿Quiénes están detrás del acaparamiento de tierras? [Who is behind the land grabbing?], 14 January 2013 (in Spanish), https://grain.org/es/article/4636-quienes-estan-detras-del-acaparamiento-de-tierras

8. Medardo Ávila Vázquez, “El agronegocio y el desmonte detrás del drama de las muertes por desnutrición en Salta” [Agribusiness and clearing in light of malnutrition deaths in Salta], 14 February 2020 (in Spanish), https://enredaccion.com.ar/el-agronegocio-detras-del-drama-de-las-muertes-por-desnutricion-en-salta/.

9. La Nación, “Eduardo Elsztain. El pronóstico económico de uno de los mayores empresarios del país” [Eduardo Elsztain. The economic forecast from one of the country’s most successful businessmen], 18 February 2020 (in Spanish), https://www.lanacion.com.ar/economia/eduardo-elsztain-la-gente-piensa-estamos-peor-nid2334858