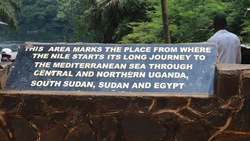

It is widely believed that River Nile, the longest river in the world, starts in Jinja, Uganda. (Photo: Fredrick Mugira and Annika McGinnis. Uganda)

Pulitzer Center On Crisis Reporting | 31 January 2020

Sucked Dry

Alice Nyamihanda was only a toddler beginning to walk and talk when she was forced away from her home. At just three years old, the child was evicted from the land where she, her family and her people had lived for centuries.

To the Ugandan public and the international community, this was an act of environmental conservation of some of East Africa’s most biodiverse natural forests that host half the population of the world’s remaining mountain gorillas.

But to the Batwa pygmies, a forest-dwelling group of hunter-gatherers who are accepted as the first inhabitants of these montane forests, the act turned the peaceful tribe into so-called environmental refugees.

Alice’s family of five and hundreds of other Batwa pygmies, a forest-dwelling group of hunter-gatherers, were evicted from their ancestral forestland in Mgahinga, Bwindi and Echuya in southwestern Uganda by the government of Uganda with no compensation when it turned the forests into conservation areas in 1991.

Since then, life has not been easy for her. Her father died in 1996. Her mother, a single parent, struggled to raise her and four other siblings. In order to survive, Alice’s mother had to offer hard labor for a number of years in exchange for a small piece of land where the family is staying now in Gatera village, Busanja Sub County in Kisoro, just on the border of Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Unlike many others in her situation, Alice has been lucky: At 31, Alice is now pursuing a bachelor’s degree in social works and administration after completing a diploma in 2010. “If God wishes, I will graduate next year,” Alice says, hoping to use the skills gained to advocate for land rights of her landless tribemates.

The Land Matrix is an independent global land monitoring initiative that compiles data on land grabs from governments, companies, NGOs, the media and citizen contributions. These are, “just concluded deals,” says Angela, and there are many other land deals underway.

The Nile River basin covers an area of 3.18 million square kilometers, almost 10 percent of the African continent, and includes 11 countries from the river’s source in Uganda up to Egypt. For the diverse peoples that live and sustain upon the Nile, the mighty life-bearing river is not only a source of livelihood, but also a cultural icon that flows with thousands of years of history, beliefs and tradition in its waters.

But in recent decades, the ancient river has been drastically manipulated as the world undergoes rapid change. Dozens of new dams have calmed millennia-old rapids and diverted the river’s natural flow. Worldwide land, water and other resource shortages, along with a globalizing economy, climate change and rapidly increasing populations, have driven countries everywhere from the Global North to the Gulf countries to search out new lands – to feed their populations, offset their carbon emissions, or simply search for new economic opportunities as the world moves toward a potential global recession.

Land Matrix data shows that 16.9 million hectares of land, or 169,000 square kilometers, from 445 individual deals have been concluded in the 11 Nile Basin countries, though some of these are outside of the river basin’s borders. There are 6.1 hectares of deals still in negotiations. Most are in agriculture, with others in forestry, renewable energy, and mining.

In the Nile basin, for every land deal, at least someone in local communities suffers. From Uganda to South Sudan, Sudan, Ethiopia and eventually Egypt, the Nile meanders through an intricate patchwork of landscapes: flat, ragged, mountainous, green and fertile, desert. The region attracts a huge number of investors each year from within and outside the region. Many of these investors remain congested close to the Nile.

Companies from countries across the world have acquired fertile Nile-irrigated land for growing food crops, non-food agricultural commodities such as alfalfa, flowers, tobacco, and biofuels, rearing livestock and logging trees. Investor countries include Austria, Belgium, Brazil, China, Ethiopia, India, Israel, Norway, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, the UK, and the USA, among many others.

Although there are a few new land acquisitions being signed now – 68 are still in negotiations - others are being abandoned in countries such as Ethiopia, and now “more of the older deals are being brought under implementation,” according to Harding, the Land Matrix data coordinator.

Generally most deals are agricultural leases and forest concessions, and very few are outright purchases. Data from the Land Matrix initiative shows South Sudan as the target of land grabbing in the basin.

It is a story told again and again. Though some deals have brought positive benefits to local economies and peoples – with models worth replicating – in most cases, it is the people in the investor countries oceans away from the Nile that reap the vast majority of the profits, while the host countries are exploited of valuable resources and the local people suffer. Their stories, of livelihoods lost, cultural icons destroyed, families torn apart – all in the name of globalization – are rarely told, or little valued.

Flowers That Dislodge People

In Ethiopia, large fields of blooming flowers colorfully mask the memories of the thousands of people who used to live and work upon these lands. Now, most of these people are living in nearby towns and cities, struggling to survive in low-paid jobs without access to the lands that had sustained them for thousands of years.

Ethiopia is the second largest flower exporter in Africa after Kenya, shipping flowers to the Middle East, France, Germany, Canada, Sweden, UK, and the Netherlands among other countries. Data from Ethiopian Horticulture Producer Exporters Association indicates that Ethiopia earned 271 million U.S. dollars from the sale of flowers and other horticulture products in 2018.

Flower selling is anticipated to bring half a billion dollars to the Ethiopian economy by 2025, according to the country’s second national Growth and Transformation Plan that aims to bring Ethiopia to lower-middle income country status by 2025.

But as Ethiopia’s floral industry blossoms, three thousand people are displaced annually in the country by flower growing investors, according to the Amhara National Regional State Disaster Prevention and Food Security Program Coordination Office. The foreign horticulture investors are accused of failing to help local communities live decent lives.

Hiwote Yazie, 27, a resident of Zenezelma Village, close to Bahir Dar city, in Amhara region said that his community members have been reduced to “immigrants on the land that once belonged to our ancestors.” She said her community did not only lose land but also water bodies. “We have natural water but we never drink it. Investors took it,” Yazie said.

The Land Matrix has documented about 1.4 million hectares of land acquired in Ethiopia in recent decades. 120 deals have been concluded across the country, with 15 deals under negotiation, which would take up another 0.5 million hectares if concluded.

Two thirds of the acquired land in the country was allocated to international investors. Indian companies have acquired the most and largest swaths of land, especially biofuels production and large-scale agriculture, including flower farms. Companies from Saudi Arabia, USA, Italy, Malaysia, China, Austria, Israel, Turkey, Canada and Singapore are also big investors.

Up to 10 of the largest horticulture investments in Ethiopia are located close to Lake Tana and the Blue Nile, covering 1,200 hectares on the Tana lakeside and another 2,000 hectares on the Blue Nile riverside, according to data from the Ethiopian Horticulture Producers and Exporters Association. The companies include Giovanni Alfano Farm, Condor Farms PLC, Fontana Horticulture PLC, Pina Flowers PLC, Arini Flowers PLC, Solo Agro Tech PLC, Tal Flowers PLC, and Joy Techfresh PLC, among others.

These companies target fertile soils and water of river Nile and Lake Tana. Asrat Tsehay, the head of the Ethiopian Blue Nile River Basin Authority, says roses consume more water than people in the region. They “consume an average of seven liters of water per stem per week” compared to “five liters of water each person uses per week,” he said.

Production of flowers in this region requires around “20,000 Olympic swimming pools full of water each year,” according to Meselech Zelalem, a water scientist with Amhara National Regional State Water, Irrigation and Energy Development Bureau. This is water from Lake Tana and Blue Nile River.

Flower farms in this region have also been accused of contaminating the two water bodies with fertilizers and pesticides. Tadele Yeshiwas Tizazu, an agriculture and environmental sciences researcher, says fertilizers and pesticides in floral farms easily leach into the groundwater. This contributes to the growth of the invasive water hyacinth plant, which is slowly destroying Lake Tana, according to Dr. Mesay Abebe, an expert analyst in Ethiopia’s floral sector.

But floral farm owners say they are working to help communities live decent lives. Sami Banchu from Giovanni Alfano Farm said they have constructed “schools and hospitals [in the region] to stimulate development.” Mohammed Mohayub of Yemeni farm said their operations meet “standard requirements,” stating that the use of pesticides is the same as “what is permitted in Europe.”

Yehenew Belay, the head of investment office for the Amhara regional state, said the government policy that targets “attracting foreign investors at the expense of the host communities” is responsible for land grabs and the suffering of local people.

A range of studies, including a 2008 report by the Forum for Environment, an Ethiopian environmental advocacy NGO, and a 2016 report by Ethiopian researcher Asnake Demena, have cautioned widespread negative effects of land grabs on the local communities in Ethiopia that were originally living on the land, including evictions and loss of access to natural resources that support their livelihoods. Arable lands, virgin forests and woodlands have also been cleared and allocated for biofuel projects, which destroys the natural ecology, the reports found.

The expert Abebe suggested that the government of Ethiopia should investigate these evictions and displacements and ensure that farmers are resettled and compensated in a manner that respects the rights of residents and adheres to Ethiopian law.

He added that a sustainable solution lies in the government of Ethiopian teaming up with the Horticulture Producers and Exporters Association (EHPEA) to formulate clear regulations that call for sustainable extraction of water from water bodies in this region for farming of flowers.

Grabbing Deserts of Sudan or Nile in Sudan?

In Sudan, land and water grabs are rampant in Khartoum, River Nile and Northern states where the Nile River passes or has tributaries, according to Stefano Turrini, a scholar involved in the study of land grabs and agricultural development in Sudanese drylands.

Stefano, a PhD candidate in Geography at Padova University in Italy, said land grabbing gained momentum in Sudan in the early 2000s, when the government of the now-ousted President Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir offered “land and water at favorable conditions to the Gulf countries.”

The Land Matrix database has tracked 762,208 hectares of large-scale land acquisitions in Sudan since 1972, with most deals concluded after year 2000. Most of this land was allocated to 28 transnational deals, with companies from mainly Middle Eastern states – including Qatar, Egypt, Lebanon, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Syria – acquiring huge swaths of land to produce food crops, alfalfa, and biofuels.

Investors from countries including Jordan, Turkey, Egypt, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia are also vying for another 3.4 million hectares of land, which are under negotiation. Alfalfa, the most commonly grown crop on the acquired land in Sudan, is exported to Saudi Arabia and the UAE to be used as animal feed.

The rush to acquire land in arid Sudan for irrigation-reliant projects reveals investors’ target for Nile water and not just land. “A great many investments combine the two,” said Tom Lavers, a lecturer in politics and development at the University of Manchester’s Global Development Institute.

Before being ousted, President Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir’s government was considering establishing more alfalfa projects. The increase in land grabbing in Sudan has pushed over the edge local communities that were already facing land scarcity due to desertification even before their lands were converted to large-scale agriculture. Many communities also lost wells and vast tracts of corridors for cattle. Because of this, “tribal conflicts” for control of “land and water resources” are flaring, according to Stefeno.

The authors termed the situation in Bukaleba a form of ‘carbon violence’ to explain how subsistence farmers and poor communities have borne the brunt of costs related to expanding forestry plantations and global carbon markets in Uganda.

The rush to acquire land in arid Sudan for irrigation-reliant projects reveals investors’ target for Nile water and not just land. “A great many investments combine the two,” said Tom Lavers, a lecturer in politics and development at the University of Manchester’s Global Development Institute.

Dispossession of land is not only associated with land but with other resources that are available in the land or near it, said Dr. Jeltsje Kemerink-Seyoum, a senior Lecturer in water governance at IHE Delft Institute for Water Education in the Netherlands. “In soil, there is always water available and most of these lands are taken away for agriculture purposes,” she said.

As a deliberate government intervention to scale down negative effects of land grabs on local communities, since 2013 the National Investment Authority has been directing private investors to allocate 25 percent of their land acquisitions to the local community. However, some investors reportedly ask for 25 percent more land than they need so that they can acquire the same amount of land after allocating 25 percent to the communities.

The Sudanese parliament has also put a ban on agricultural investment ventures, with members of parliament citing depletion of the country’s underground water resources.

Gulf Companies Grabbing Reclaimed Desert Lands

In Egypt, corporations from arid Gulf countries facing an impending water crisis have capitalized on the country’s strategy to “reclaim” desert land for agricultural production to boost their own imports.

In the Western Desert, rapid changes are in full swing to make green what was mostly sandy desert two decades ago.

Vast expanses of green extend across the horizon, tended by the advanced machinery that has replaced hundreds of agricultural workers. The land is watered using center-pivot irrigation systems, connected to one another in a series of canals through which water is driven by one of the biggest water pump stations in the world.

A number of engineers oversee the expansion works to cultivate new fields of alfalfa on land run by one of several Gulf investment companies in the Toshka project.

The desert’s greening is part of an agricultural development and investment initiative framed as aid to the Egyptian people. But in fact, Gulf corporations acquired most of the land as part of the oil-rich countries’ plan to ensure their food security by cultivating land outside their borders.

In January 2009, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia launched the King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz initiative for agricultural investment abroad, outlining plans to achieve food security by investing in countries with agricultural potential.

This initiative included offering financial support to Saudi investors, with the government covering up to 60 percent of construction and production costs. The government also committed to negotiating bilateral agreements with other governments to facilitate business for investors abroad and secure the export of at least 50 percent of their produce to the kingdom.

This long-term agricultural strategy evolved with one ministerial decision after the other, starting from limiting wheat cultivation in 2005. A 30-year program of wheat production and cultivation in the kingdom then decreased gradually until it was completely halted in 2008 due to concern over the depletion of water resources. Last year, while the Saudi government lifted the ban on wheat farming under certain conditions, the cultivation of green feed was completely banned as it consumes up to six times more water than wheat.

Saudi Arabia wasn’t the only Gulf country with an impending water crisis. The United Arab Emirates was also facing diminishing water resources and turned to importing about 90 percent of its food. The UAE thus also began to push for investment in farming ventures abroad.

Facing similar challenges, the two countries jointly announced “The Strategy of Resolve” last year to strengthen economic, political and military cooperation. This includes establishing a unified strategy for food security, with plans to harness the full potential of agricultural and livestock production and to work together on joint projects.

In the last few years alone, the Emirates has managed to gain control over almost 4.25 million feddans of land spread out over 60 countries, while Saudi Arabia now controls about 4 million feddans around the globe. (1 square kilometer is equal to 238.09 feddans)

Some define the rush by richer countries to buy or lease large expanses of land in countries with agricultural potential as a form of neocolonialism, which achieves food security for the investing countries while exploiting non-renewable resources, including water, in the farming countries.

Gulf investors found their panacea in Egypt, which is increasingly adopting a capitalist agricultural production model that prioritizes investment in large-scale, modernized farming to export crops over pursuing strategic crop cultivation and traditional farming methods in the Nile Valley and Delta.

In Egypt, the Land Matrix has tracked 14 land acquisitions making up 185,000 hectares – almost all in the agricultural sector – with another 151,000 hectares in negotiations.

“Come along with me around Egypt to see what has become of our country, a different picture than two years ago, or three. Between two reigns, I do not compare, or despair, or shout in glee. It’s my children’s right to see Egypt, my country, in the millennium, shining new as can be.”

So went the anthem played on all state-run Egyptian TV channels in early 1997 during the visit of former President Hosni Mubarak to Egypt’s Western Desert, just 225 kilometers south of Aswan. In what became an iconic photograph of the Mubarak era, he can be seen raising his hands in salute to the engineers to inaugurate the Toshka project.

The project’s plan was designed to start construction in 1997 through to 2017. The main objectives were to erect a new Delta south of the Western Desert, add up to 1 million feddans of farmland, create new industrial and residential communities, and generate 45,000 new jobs every year to accommodate 4-6 million Egyptians in 10 years.

But years have gone by, and Egypt has not noticeably benefited from the Toshka project. The crisis of overpopulation in the Nile Valley and the issue of food security remain unresolved. The project has, however, achieved considerable success for some foreign investment companies.

The Emirates gained a foothold in the project as early as 1997, with a $100 million donation made through the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development. The money went toward constructing and lining the project’s main water canal. Extending for about 51 kilometers, it has since been renamed the “Sheikh Zayed Canal” after the ruler of Abu Dhabi.

The concerned authorities earmarked one-tenth of Egypt’s total quota from the Nile’s water (5.5 billion cubic feet out of 55.5 billion cubic feet) for the project. A 250 MW pumping station was built to pull the water from Toshka valley, which is linked to Lake Nasser and filled from flood water, to the Sheikh Zayed Canal, which then feeds four branches extending along the areas to be “reclaimed.”

After water was pumped into Sheikh Zayed Canal in 2003 for the first time, it brought with it an influx of Gulf investors into the Toshka area. The Toshka project currently spans about 405,000 feddans, 49.4 percent of which are owned by the Saudi-based Al Rajhi International for Investment company and the Emirates-based Al Dahra for Agricultural Development company. The Egyptian government and state-owned agricultural reclamation companies also own shares in the project.

Suspicious contracts

The contracts between the Egyptian government and Gulf investors, particularly in Toshka, are rife with violations, according to information released in previously published media reports, as well as copies of the official documents obtained by Mada Masr.

In 2011, the Egyptian Center for Social and Economic Rights filed a lawsuit against Al Dahra calling for the annulment of the contract. The lawsuit stipulated that the sale of 100,000 feddans of land in Toshka to the company involved gross squandering of public funds and the sale of state land at a lower price than the estimated market price, since the land was sold at LE50 (US$3) per feddan at a time when the average land price was LE11,000 EGP (US$637) per feddan.

A handful of lawyers have filed lawsuits against some of the Gulf companies intertwined in Egypt’s network of agricultural investment, contesting that some of the contractual terms had violated Egypt’s Constitution and squandered the country’s resources.

According to a lawyer who worked on one of these lawsuits, major corporations often operate under a web of entangled investment interests as a strategy in order to gain complete monopoly over the market under the guise of multiple companies.

The lawyer, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said that this strategy also helps cover up how much control a certain investor exerts over the market, because the share is distributed over several companies, which also makes tax evasion easier.

This arrangement ensures benefits for all entities involved. For example, the Saudi company Al Rajhi, which grows alfalfa, a grain cultivated to feed livestock, is an affiliate of Almarai, a dairy production company. It’s also an affiliate of Alkhorayef, which works in irrigation systems. All of these companies operate under the Saudi agricultural investment conglomerate Jannat, which helps them expand their market share and meet their supply demands. It also facilitates indirect deals with other companies like Wafrah, a Saudi food products company that makes grains and pasta, and Marina, an Egyptian company that works in animal feed production.

Expansion works to cultivate new fields of alfalfa on land run by one of several Gulf investment companies in the Toshka project. Image by Nada Arafat and Saker El Nour. Egypt, undated.

Expansion works to cultivate new fields of alfalfa on land run by one of several Gulf investment companies in the Toshka project. Image by Nada Arafat and Saker El Nour. Egypt, undated.

This investment strategy aims to control the entire food supply chain, starting from the production materials to the production and industrial processing and, lastly, the market in order to exert complete monopoly over food commodities.

We’re buying water, not alfalfa

In official statements about agricultural acquisitions, investors stress their concern with preserving water resources and the long-term sustainability of their projects through producing crops for local consumption. But the reality is quite different.

In Egypt’s case, the government has pressured the companies to cultivate wheat as one of the strategic crops that sustains most Egyptians. However, the government has failed to supervise the companies to ensure uptake of wheat. According to a source working at one of the Gulf companies in Toshka, who spoke on condition of anonymity, the total wheat produced by the company was only 15,000 tons, meaning that the total area cultivated with wheat was only about 6,000 feddans.

In water-scarce Egypt, the investors acquired a huge amount of water at an extremely low cost. In an economic feasibility study he prepared, Seyam explained how the total area cultivated by both companies was about 29,000 feddans. The average amount of water consumed is about 210 million cubic meters annually, while the companies pay the Ministry of Irrigation about LE20 million (US$1.2 million) annually. If we estimate that the market price for a cubic meter of water is LE2 (US$0.12), this means that the investor purchased water worth LE420 million (US$24.3 million) for just LE20 million (US$1.2 million).

This “water grab” is not limited to the 29,000 feddans which make up the currently cultivated area of land, but extends well into the future when the two companies will own 200,000 feddans between them.

Seyam’s analysis was confirmed by a source working at one of the two Gulf-owned companies in Toshka, who quoted one of the Emirati alfalfa importers as saying: “We’re buying water, not alfalfa.”

The same amount of water, around 210 million cubic meters, said Seyam, would be sufficient to cultivate 84,000 feddans of wheat, thus raising Egypt’s production of a strategic crop by about 62,000 tons. Egypt consumes about 16,000 tons of wheat annually and is the world’s largest wheat importer. Last year, it imported about 6 million tons of wheat.

Hamdy Abdel Dayem, the official spokesperson for the Egypt’s Ministry of Agriculture, said most contracts limit investors to cultivate only 5 percent of land with alfalfa in order to protect water resources. But MP Raef Temraz, the former deputy for the parliamentary committee on agriculture and irrigation, did not believe this.

He said alfalfa cultivation takes up 25 percent of the total cultivated land in Toshka and the New Valley governorate. Temraz noted how alfalfa is exported in huge quantities to a number of Arab countries, chiefly Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Gamal Seyam, a professor of agricultural economy at Cairo University, stated that this type of foreign investment gives zero return to the state because it allows investors to buy the water for cheap, acquire land at a low cost and export most of their produce. Furthermore, the capital for these corporations is not based in Egypt. Thus, there is no real benefit to the national economy.

Land Deals Gone Bad

Near Kisumu town along Lake Victoria in Kenya lies the graveyard of a once 60-square-kilometer massive American farming institution.

On the shores of this enormous lake that sustains the fishing economies of Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania, towering rice silos and a sugarcane processing plant lie eerily idle, slowly falling into disrepair. Spilling out of a huge empty workshop are strewed a hapless collection of defunct agricultural equipment, including tractors and ploughing machines.

The only sign of life in this desolate scene are a few women from the community, bathing their naked toddlers beside a small stream, and the lazy grazing of cattle, milling around the abandoned farming tools.

This is the sad outcome of Dominion Farms Limited, an American company that acquired a 175-square kilometer area of swampland next to Lake Victoria with a 25-year lease to conduct large-scale rice, banana, cotton and sugarcane production as well as aquaculture farming.

Touted as the single largest investment project in the Lake Victoria region of Kenya, the Dominion Farms’ agricultural interests were initially hoped to be a major boon to the economy of Siaya County.

Besides creating jobs for the local residents, it was hoped that this investment windfall would have the ripple effect of stimulating the entire economy of the poverty-afflicted lake basin region.

But with 12 years remaining on its lease, the U.S. investor abandoned the project when its CEO Calvin Burgess swiftly left Kenya due to what he called an unfavorable business environment, the Standard reported.

Over the company’s tenure in the 200-square-kilometer Yala Swamp, thousands of local residents complained that their lands were unfairly stolen.

Originally, part of the swamp was controlled by the Lake Basin Development Authority (LBDA), an oversight government agency in the Lake Victoria Basin. At the time, the government used to occupy the left-hand side of the swamp, whereas the community worked the land on the right-hand side.

But two local county councils leased away the land to Dominion without community input, leaving the local people without a means of livelihood.

Community members tried to force their way back into the swamp, clearing papyrus reeds and planting small farms to grow food for survival. But the government would frequently drive them away, displacing a total of 6,000 people as a result, according to Jacob Ouma, the area chief of Kadenge Sub-location of Siaya County.

Over its 13 years, aerial spraying of chemicals on the swampland destructed fragile wetland environments that are key to purifying water that enters Lake Victoria as well as serving as the breeding ground for the African catfish fry, according to Christopher Aura, assistant director of the Freshwater Systems Research at the KMFRI’s Kisumu Centre.

A recent technical report by the KMFRI, which is still in the process of being published in a scientific journal, found that River Yala is one of the two major rivers north of Lake Victoria that majorly contribute to pollution in the lake. This river directly parallels the former Dominion Farm.

These latest findings are consistent with another study published in 2014 in the International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR). “This study observes that degradation of the environmental resource base such as excessive resource extraction and severe land use by Dominion Irrigation Project has not only affected the quantity and quality of the services that are produced by ecosystems, but has also challenged the resilience of the Wetland to ensure sustainable development for the households in South Central Alego,” the study found.

As with many large-scale land acquisitions, the investment spurred some community development just as it harmed the environment and local livelihoods. Dominion assisted several several local primary schools to gain new classrooms, wrought-iron goalposts and rehabilitated playgrounds. The farm was also the first in the area to implement research by the Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute, including introducing cage fish farming in Lake Victoria in 2005, according to Veronica Ombwa, a research scientist at the institute.

52 land deals making up about 393,000 hectares have been signed and concluded in Kenya since the year 2000, according to the Land Matrix. Foreign and domestic companies have invested primarily in agriculture, renewable energy, conservation, tourism and forestry.

With 160,000 hectares allocated to the project, the Bedford Biofuels is the largest of any such deals yet. The project intends to invest in jatropha plantations in the Tana River Delta.

Enslaving Local Communities

In resource-rich Democratic Republic of the Congo, lands in the northwest Equator region are parceled out into foreign investments targeting tree logging, mining and growing of food crops, according to Land Matrix data.

There are 87 deals taking up 10.6 million hectares of land across the DRC, according to the Land Matrix – the highest amount of all Nile basin countries, though only a small part of the vast country is actually part of the river basin. Of these, forest logging takes up the vast majority (53 deals) of the acquired land, with an average deal size of 184,623 hectares and the largest deal taking up 383,255 hectares.

A study of land-grabbing, agricultural investment and land reform in DRC by Chris Huggins, a researcher on land and natural resources rights in Sub-Saharan Africa, identified USA, Germany, Belgium, France and South Africa and China as some of the main investing countries in the DRC. The Land Matrix also identifies Switzerland, Canada, Liechtenstein, Lebanon, and the UK as other major investors, particularly in logging.

In June 2018, an investigation by Global Witness, an international NGO focused on human rights abuses and corruption, found rampant illegal logging across 90 percent of sites owned by Norsudtimber, a European company registered in Lichteinstein that logs in more than 40,000 square kilometers of rainforest in the DRC.

Dorothee Lisenga, the coordinator for Coalition des Femmes Leaders por l’Environnement et le Development Durable (CFLEDD), a Congolese NGO that strives for the recognition of women’s land and forest rights in the provinces of Equateur and Maindombe in the DRC, said women are the most affected group by land grabbing in the country.

She said apart from denying local communities, “farmlands and food”, land grabs have turned most local communities into, “slaves working on investors’ farms and mines on land that once belonged to them.”

Most members of the CFLEDD organisation are indigenous pygmy women. Congolese pygmies live forest-based hunter-gatherer livelihoods in the forests of the DRC, the world’s second largest forest. Citing research by her organization, Lisenga says 70 percent of women in the DRC do not have access to land and forest titles.

Forests in Uganda

Lakeside communities trapped under the guise of fighting climate change

Otewu John never thought he would end up in a life of crime. But when the 56-year-old’s garden of 20 years was slashed and he was forced from the land, he found himself resorting to illegal fishing, lacking the small amount of money needed to invest in a more expensive legal fishing net but needing to provide for his 9 children.

The fisherman first moved to the tiny remote village of Walumbe along the shores of Lake Victoria in 1984, searching for prime waters in which to fish for tilapia and other species.

He soon landed upon a better opportunity, discovering a huge expanse of seemingly unused land within a 9,000-hectare forest located deep in Mayuge District, Uganda. There, many other villagers were already planting small gardens among the trees, growing maize, cassava, potatoes and other crops to sustain their families and sell for small profits.

For decades, hundreds of people provided for themselves from these gardens and other resources obtained from the forest, including firewood, grazing land for their animals and sources of freshwater. But when the the National Forestry Authority leased the land to Norway-based Busoga Forest Company in 1996 to plant pine and eucalyptus trees for timber export, these people, who had no official land titles, were forced from their gardens. About 830 families were evicted from about 360 hectares of land that they used to farm, according to David Kureeba, a Program Officer at the National Association of Professional Environmentalists, which conducted a research and advocacy campaign about these communities.

Many of the people had migrated to the forest to work on a government beef farm and center to fight the parasitic sleeping sickness during former President Idi Amin’s regime in the 1970s. Others came escaping warfare in the north in 1987. When the current government came into power, the area was re-gazetted as a forest reserve, but “the gazettement was kind of informal,” Kureeba said.

So the people remained, many claiming not to have been given terminal benefits after the government projects closed. People continued to come. Between 2002 and 2010, these villages grew by an average of 53 percent, according to a 2011 Ministry of Water and Environment report.

Today, there are four communities making up a total population of about 7,500 people located within the reserve, three along the lakeshores and one within the forest.

The National Forest Authority (NFA), the government body entrusted with managing forest reserves, contends that the area was gazetted as a reserve in 1948 and therefore these people are landless encroachers who “just forced themselves on the land which was not theirs,” according to Steven Galima, NFA Natural Forests Coordinator. But complex land laws in Uganda do give some rights to people who settled on land 12 years before the 1995 Constitution came into place.

In April, the government through NFA and the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) began degazetting about 3,000 hectares of the 9,000-hectare Bukaleba Forest Reserve along with areas in the nearby South Busoga Forest Reserve, partly to find land to resettle dozens of villages that were evicted from the South Busoga area decades ago, Galima said.

The land currently occupied by the Bukaleba forest communities will be degazetted, as well as the 200-meter buffer zone alongside Lake Victoria that must be maintained to reduce pollution and conserve the environment of the lake, according to Stuart Maniranguha, the Kyoga Range Manager at NFA. Lake Victoria is the largest lake in Africa and shared by three countries that depend upon its resources, but pollution by the growing populations living near the lakeshore has severely polluted the water body and reduced its fish populations, a key economic resource.

But when NEMA completes the 200-meter demarcation within the next several months, the people living along the lakeshore will be made to leave their homes according to Naomi Karekaho, NEMA corporate communications manager, whether they get compensation for the value of their lost land and crops or resettlement on degazetted land will be determined by the Office of the Prime Minister in time to come.

While National Forest Authority officials said the four villages that exist within Bukaleba are not likely to be among those resettled, the beneficiaries are still being identified, according to the Mayuge District Chairman, Hadji Omar Bongo, and the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development Public Relations Officer, Owbo Dennis.

Bongo also claimed that these forest communities will also be officially allocated a small portion of land within the degazetted area to sustain their livelihoods, a struggle that has been ongoing for eight years. Currently, the villages are fighting over a 500-hectare allotment that has been dominated by just one of the four communities.

Busoga Forest Company’s tree plantation is one of 6 large-scale forestry projects in Uganda with deals taking up a total of 47,339 hectares. Owned by companies from countries including the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands and Norway, most of these concessions are monoculture plantations of non-native, fast growing tree species such as pine and eucalyptus that are cut and sold as timber in Uganda and abroad. At the same time, many of the companies say they are fighting climate change through reforesting degraded lands and selling ‘carbon credits’ to polluting companies abroad. Investing in commercial forests is a national strategy to increase revenue and wood-based products to the Ugandan people, according to Galima from the NFA.

But while such projects are intended to inject economy and development into poor, low-resource areas, in many places, including Mayuge, their presence has often ended up depriving the most marginalized communities of their livelihoods without adequate efforts to replace them. People already living on the margins of society end up further ignored, and with even less.

One of these villages is Walumbe, population 1,500, a tiny landing site of grass-thatched houses nestled in a 200-meter buffer zone between Lake Victoria and wall of perfectly spaced trees marking the Busoga Forestry Company plantation.

After their forest gardens were slashed, residents of Walumbe resorted to fishing to sustain their lives. But lacking enough money to invest in legal fishing gear such as nets that do not harm small fish, the fisherman say they are forced to use cheaper illegal nets and thus face the constant threat of arrest.

Without money for strong boats or lifejackets, the waters aren’t safe. This year, one fisherman was eaten by a crocodile. Residents first found his shoes, then his torso.

“You fish on the gunpoint now,” the fisherman Otewu said.

The Land Matrix has tracked 238,033 hectares of large-scale land acquisitions in Uganda since 1990, with most deals concluded since year 2007.

Most of this land was allocated to 25 transnational deals by investors from countries including the United Kingdom, Germany, Mauritius, Norway, and India. Twenty-seven deals are currently in production, including another 10 domestic deals by Ugandan companies or the government. Investors from Bangladesh, the UAE, Saudi Arabia and India are also in negotiations for another 12,500 hectares of land mainly for export agriculture.

Busoga Forestry Company (BFC) obtained a 50-year lease of 10,054 hectares in Mayuge District in 1996, according to the Land Matrix. According to John Ferguson, the managing director of Busoga Forestry Company, the total area BFC plants in Mayuge is 6,300 hectares, and the remaining 2,700 hectares goes to conservation along with the 500 hectares for community activities.

Busoga Forestry Company is a subsidiary of Green Resources AS, a private Norwegian company established in 1995. Green Resources claims to be East Africa’s largest forest development and wood processing company, with 38,000 hectares of forest in Uganda, Mozambique, and Tanzania, a sawmill in Tanzania and electricity pole and charcoal plants in the three countries. The company manages 15 plantations including two in Uganda and in 2016 had net sales of $5,673 according to its 2016 Environment and Social Impact Report.

On its website, the company says it is one of the first companies in the world to benefit from carbon revenue from its forests. Under the international REDD+ scheme, carbon-emitting companies that contribute to climate change have an option to “offset” their negative emissions by buying “carbon credits” from tree-planting initiatives elsewhere in the world.

This year, BFC will sell about 325,000 tons of carbon, including 65,000 tons from Bukaleba, to the Swedish energy agencies under the United Nations advanced market operated by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, according to Ferguson of BFC.

But time and time again, this model has proven too good to be true. In a 2018 study published in the Global Environmental Change journal, researchers at the IHE Delft Institute of Water Education in the Netherlands found that two participatory forest conservation projects in Ethiopia that supply carbon credits as part of the REDD+ scheme had ended up aggravating conflicts over the use of natural resources among the local communities. Another 2018 study published in the Climate Policy journal found a “a gap between the REDD+ narratives at international level… and the livelihood interests of farming communities on the ground,” referencing also a climate finance forestry projects in Indonesia.

According to John Wanyu, a gastroeconomist scientist at Slow Food Uganda, an NGO that promotes the development of sustainable food communities, the planting of monoculture alien tree species such as pine and eucalyptus also uses huge amounts of water and destroys the natural biodiversity of the environment.

But the Ugandan government claims that investing in commercial forests is a lucrative venture for the developing country, which makes 30,000 shillings ($8) per hectare a year in ground rent – amounting to about 190 million shillings ($52,000) a year for the company’s 6,400 hectares. Ferguson said his company contributes 2-3 million dollars a year to the Ugandan economy in taxes alone. One hundred percent of the company’s products are sold domestically, most to the national electricity supplier UMEME as electrical poles, he said.

In 2016, eighty-six percent of BFC’s products in Uganda were sold domestically, according to Busoga Forestry Company’s 2016 Environment and Social Impact Report.

Busoga Forestry Company is not the only forest deal in Uganda. In the country, 3 of the top 4 transnational deals making up a total of 42,236 hectares are in forests, with companies from the United Kingdom, Germany and Norway investing in monoculture timber plantations located on government-run forest reserves in eastern, western and central Uganda. These deals have all been rife with similar controversies as the Mayuge deal.

Smaller land acquisitions have also affected many Ugandans. Constance Okollet, chairperson of Osukuru United Women Network based in Osukuru Sub County, Tororo district of Uganda said 100 women out of the 1,286 women that belong to her organization are now facing untold suffering after their husbands sold their family land to Chinese investors. And for some women whose family land was acquired by investors, their husbands used the money they were paid to marry more women. The rest was spent on alcohol, according to Okollet.

While much public attention has been on such deals by foreign investors, most land grabs in Uganda are actually by individual Ugandans who encroach upon protected or private lands, according to Isaac Kabanda, the Food Community Coordinator at Slow Food Uganda, an NGO that promotes the development of sustainable food communities.

For example, River Rwizi, a lifeline river for over four million people in southwestern Uganda, has seen up to 80 percent of its water dry up as a result of land taken by individual Ugandans. 200 people have illegally acquired over 500 hectares of land along River Rwizi, destroying wetlands on its banks.

Community development?

On its website, Busoga Forest Company affirms its commitment to developing the communities affected by its projects and mitigating negative impacts of its presence such as loss of livelihoods.

Ten percent of company profits are intended to be used to develop the community.

“Green Resources’ strategy is based on the sustainable development of the areas in which it operates. The company believes that forestation is one of the most efficient ways of improving social and economic conditions for people in rural areas and aims to be the preferred employer and partner for local communities in these areas,” the company writes on its website.

In Bukaleba village, about 120 villagers are employed in the company as slashers, sprayers, and termite killers, the village chairman Aliphonse Ongom said. But in a month, the average employee makes only 60,000 Uganda shillings – about $16 – despite claims from BFC that they pay a monthly minimum wage of 205,000 Uganda shillings, according to the company’s 2016 Environment and Social Impact Report.

After conflicts with the local communities, BFC agreed to a ‘Collaborative Forest Management Programme’ in October 2011 that stipulated that 1.1 billion Uganda shillings (about $296,000) would be spent over the next five years to strengthen company-community relations and support the communities through various capacity building activities. Most of this money would come directly from the company, the agreement stated.

Dividing 1.1 billion Uganda shillings by five, it was expected that BFC would spend on average about 218 million shillings per year on community development. However, according to the publicly available Environment and Social Impact Reports released by BFC, the company spent only about 30 million shillings on community development in 2015 and 128 million shillings on the same in 2016.

However, according to the managing director of BFC, the company has been able to contribute more to community development since it finally became profitable in 2018. The company spent about $125,000 USD (about 462 million shillings) for community development in 2018, and this year it plans to spend about $250,000 (about 924 million shillings), Ferguson said.

The 2011 agreement also promised that BFC would contract plantation management to the local communities, hold skills trainings and mobilize resources for community income generation projects, and demarcate a community tree growing zone of about 30 meters from the line of the present settlements. The agreement also promised to move other settlements such as Bukaleba and Walumbe into the larger Nakalanga village.

But as of July 2019, none of the other settlements had been moved into Nakalanga, leaving them unable to access the 500-hectare community land located around Nakalanga. There was further no evidence or discussion of such a community tree growing zone around the four villages within the forest. Ferguson of BFC said that the communities had been provided with seedlings, but while a 2018 Social Impact report provided by the company specified that 74,518 seedlings had been issued to community members in Kachung, there was no mention of Bukaleba.

According to Green Resources and BFC reports, some of the projects the company has undertaken to support the local communities include constructing three new water boreholes in 2018 in Bukaleba that benefited more than 3,000 people; providing medical supplies for two health centers with a monthly patient count of about 1,223 people, expanding a medical dispensary, maintaining more than 35 kilometers of community roads, sponsoring three girls to attend higher education, and increasing HIV/AIDS awareness with support from the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation. BFC also implemented a multiyear improved cook stoves project that trained 256 people from 8 villages in 2016. Green Resources further permits community members to harvest small sticks from the forest to use as firewood, Omoro, the Nakalanga village resident, said.

But after training a group of Community-Based Organizations in the villages, the company left without providing the promised startup capital except to a single group, said the village chairman Ongom.

Villagers further maintained that losing the land where they grew food to survive was still the source of almost all their problems and one that has never been adequately addressed by the company or the government. The government maintains that they never had rights to the land.

According to Ferguson of BFC, the company has increased food security for more than 1,823 households in its two forest reserves in 2018 through distributing cassava cuttings and groundnut seeds. In the entire history of the project, the company has helped ensure food security for more than 12,761 people, according to a report compiled by Kizza Simon, the company’s 8-year ESG Manager.

Ferguson said the company had nothing to do with any history of communities being forced off their lands. When BFC came in in 1996, nobody was on the land, and since then, the company has invested a large amount of resources to support the neighboring communities, he said.

“NFA put out a tender for people to operate on these plantations. We applied for that tender and we were successful based on our plan for what we would do. We moved onto land that required to be planted; there weren't any people there when we moved onto it, and the history behind it is something that NFA would be able to give a lot more insight than we can.”

A 2014 report based on more than 150 interviews by the Oakland Institute, a U.S.-based environmental think tank, found that more than 8,000 people in Bukaleba and Kachung Forest Reserves had faced “profound disruptions to their livelihoods” due to the presence of Busoga Forestry Company, including forced and violent evictions, the denial of access to land that sustained them to grow food and graze cattle, and the lack of access to forest resources.

Alibhai of the National Forest Authority said the communities need to “seek help” by officially writing to the NFA to be recognized as a formal Community Forest Management group, after which NFA can support them such as by giving them trainings in tree nursery management, among other benefits.

According to Ferguson of BFC, while forestry projects have often been condemned as the “smelly family member,” the sugarcane plantations such as Kakira Sugar Works that own more than 50,000 hectares near BFC’s operations in Mayuge actually take in 15-20 times more water than trees while leaching land that used to be used to grow food crops.

“The perception of forestry around the world is that they’re seen as the bad boys for some reasons, maybe because trees are big beautiful things and how can you cut them down and yes those are the realities,” Ferguson said. “But if you look at how sugarcane is taking out the business of the gardens and where people are growing their crops, you see it’s getting dryer and dryer every year.”

Hunger Strikes as Acquired Land Lies Idle

In South Sudan, a young country mired in a decades-long conflict, the scramble for land along River Nile by foreign investors has seen swaths and stretches of hectares of fertile communal lands being allocated without the due involvement of local communities. Though renewed conflict in 2016 drove many investors away, some have come positively to help grow food to ease the country’s hunger crisis.

The Land Matrix database has tracked about 2.6 million hectares of land grabbed in South Sudan since 2006, with another 1.5 million hectares of intended deals.

Most of this land was allocated to 11 transnational deals, with companies from the UAE, Sudan, Norway, UK, Saudi Arabia and Egypt acquiring vast swaths of land for food crops, timber production, carbon sequestration and tourism.

Until the 2016 civil war, foreign investors such as ones from the United States, United Kingdom and some Arab countries owned about 10 percent of the country’s land for extracting resources, oil mining and agricultural production, according to the Norwegian People’s Aid-South Sudan.

The land acquisitions were largely in the greater Equatoria region and some parts of Bah er Ghazel region where thousands have been displaced by the renewed conflict in July 2017.

Massive land grab in these regions were focused on resource extraction, oil mining and agricultural production, RT News reported.

Along the Nile River on Gumbo to Rajaf Road, about 10 kilometers south of Juba city, a running row of signposts with many in Chinese language indicate how far and wide investors have come for a stake of these prime Nile-irrigated lands.

Forty-eight-year-old Paulina Wani, a Bari by tribe, decried land grabbing in her ancestral land. The mother of seven said the stretch of land between Gumbo and Rajaf belonged to the Bari community, but individuals have been pushing them out since conflict in the 1980s.

It was at this time that some politicians and multinational companies started targeting fertile land along River Nile, she said.

“Can you believe they have grabbed even the small highlands in the river? Those small 10 by 10 feet patches you see there have their owners,” Wani said as she pointed at the tiny and rocky islands.