A man watering his vegetable garden at Bopiat village in the Northern province of Louang Namtha where Chinese workers are carrying out drilling works for soil analyses in preparation of building a railway linking China to Lao. (Photo: AFP)

Dying for land in Lao?

by Sheith Khidhir

Reports recently surfaced revealing that 69-year-old Thitphay Thammavong had been arrested in Lao last month on 16 September. His crime? According to his family members, he had refused to sign papers that would give up control of his 1.5-hectare plot of land near Viengkham village in Bolikhamsai province’s Pakkading district so authorities could build a health centre on it. Thitphay Thammavong’s family members say the land has been in his family since 1965.

Authorities, on the other hand, have denied the family’s claims and said that the land belongs to the state.

“This lot of land belongs to the state, contrary to what the family claims. The state reserved this land for economic development since 2001. Since then, nobody encroached on it until 2009,” an official of Pakkading district told Radio Free Asia (RFA).

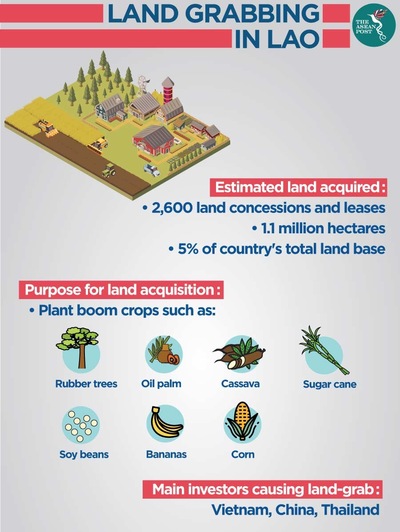

Nevertheless, it is pertinent to note that as far as Lao is concerned, the country has often come under criticism for land grabs in which authorities seize land from the people for development projects. Allegedly, this happens without paying them fair compensation.

In July 2017, 15 residents of Yeub village in the Sekong province of Lao were taken into custody for obstructing workers and cutting down trees on their former land. The land had allegedly been taken by the government and given to a Vietnamese rubber company.

But that’s not all. According to international reports, several of those detained were beaten or subjected to electric shocks in the days following their arrest, with another later reported to have died in custody.

This isn’t the first case of protesting residents being taken into custody. In 2011, 25 protestors were taken into custody following a land protest in the country’s Salavan province. All but two of the 25 protestors were released while the other two were imprisoned. In April, one of those two prisoners, Sy Phong, died and despite officials citing natural causes. Villagers fear the death might have been caused by torture.

Sy Phong and another accused leader, Som Nuk, had protested outside district offices with a group of 25 residents of Salavan’s Dane Nhai village to call for the return of land given by the government to a Vietnamese company to grow eucalyptus trees.

Allegedly, even when compensation was promised, it wasn’t followed through. According to reports that surfaced in October last year, 80 families in Pak Houei village in Champassak province’s Pathumphone district signed an agreement in 2009 with Vietnam’s Daklak Rubber Company under which villagers would provide labour and 700 hectares of land for cultivation, with profits shared at 80 percent for those owning the land.

Claiming growing losses over the next four years, Daklak then renegotiated its lease to terms more favourable to the firm, with villagers and the company taking profits in a new 50-50 split. But three years later, still losing money, the company brought in Vietnamese to work the land, saying the Lao villagers were poor workers; offering them compensation for the land’s use instead.

Later, however, all payments from Daklak ceased, with Daklak demanding proof the villagers owned the disputed land on which they have supposedly paid taxes and grown corn, bananas, and vegetables for generations.

Not giving a dam?

The story doesn’t end here. By now most know of the tragic dam collapse in Lao. Described as the country’s worst flooding in decades, the disaster occurred in July last year when a saddle dam at the Xe Pian Xe Namnoy (PNPC) hydropower project collapsed following heavy rains, inundating 12 villages and killing at least 40 people in Lao’s southern Champassak and Attapeu provinces, leaving many more missing.

Following the disaster, a 2,000-hectare plot of compensatory land near Pindong village, Sanamxay district, Attapeu province was cleared by authorities three months ago on the understanding that the victims of the disaster would be able to grow crops there during the rainy season in 2018. Unfortunately, the authorities allowed a Chinese investor to plant bananas there instead.

According to reports, survivors of the Xe Pian Xe Namnoy disaster are concerned that the land they were promised is going to a Chinese developer.

As with most things, there are two sides to the story as far as land-grabbing goes in Lao. The government and authorities continue to deny that they are “stealing” land from their people. Nevertheless, human rights advocates, researchers and numerous cases seem to paint a different picture.