Tax havens and Brazilian Amazon deforestation linked: study

by Giovanni Ortolani

-

Tax havens are found in countries that demand no or low taxes for the transfer of foreign capital through their jurisdictions. Typically, tax havens, like those in the Cayman Islands, are very secretive and lack transparency.

A rancher at the Jacutinga cattle ranch in Figueirópolis d´Oeste, Brazil. These cattle are destined for the Marfrig slaughterhouse. Environmental NGOs are calling for all companies in the Brazilian beef supply chain to refuse products sourced from Amazon ranches that have carried out illegal deforestation. Photo: © Ricardo Funari / Lineair / Greenpeace.

A rancher at the Jacutinga cattle ranch in Figueirópolis d´Oeste, Brazil. These cattle are destined for the Marfrig slaughterhouse. Environmental NGOs are calling for all companies in the Brazilian beef supply chain to refuse products sourced from Amazon ranches that have carried out illegal deforestation. Photo: © Ricardo Funari / Lineair / Greenpeace. - This secrecy protects institutional or individual investors from being in the public spotlight when making investments that are controversial, such as those in agribusiness companies in Brazil known to have caused significant Amazon deforestation, or those investing in illegal fishing.

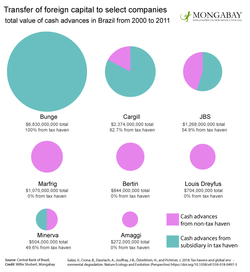

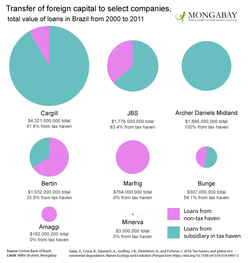

- According to a recent study, between 2000 and 2011, 68 percent of all investigated foreign capital to 9 top companies in the soy and beef sectors in the Brazilian Amazon was transferred through tax havens. Soy and beef production cause major Amazon deforestation. Also, 70 percent of vessels known to be involved in illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing were funded via tax havens.

- Better transparency is needed so that investments moved through tax havens can be tracked so as to determine their impacts on the environment and on indigenous and traditional communities. This improved transparency would likely result in greater public scrutiny and force greater responsibility on investors who today remain largely anonymous.

Money flowing from secretive tax havens is fueling deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon and threatening fish stocks. That warning comes from a report published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

A study found that between October 2000 and August 2011, 68 percent of all investigated foreign capital to nine major companies in the soy and beef sectors in the Brazilian Amazon was transferred through one or more tax havens.

And while today only 4 percent of all registered fishing vessels are flagged in a tax haven, 70 percent of the boats implicated in illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing are, or have been, flagged under a tax haven jurisdiction.

“We started a research project two to three years ago trying to explore the links between financial flows and modifications of “sleeping giants,” – key biomes in the world of critical importance for climate stability,” Victor Galaz told Mongabay. He is Associate Professor and Deputy Director at the Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University and lead author of the study.

Galaz and his colleagues focused on the Brazilian Central Bank’s website, a data goldmine where the research team found hundreds of PDFs that record transfers of foreign capital made from abroad to companies domiciled in Brazil. “Wouldn’t it be interesting to see how prominent tax haven jurisdictions appear in the data?” Galaz thought at the start. As their findings show, it was interesting indeed.

What is a tax haven?

The study lists more than 40 tax havens from around the world, headquartered in nations as diverse as Costa Rica and Switzerland, and all with different underlying structures – a fact that’s made it difficult to define the nature of this economic mechanism, resulting in a decades-long debate among scholars.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) defines a tax haven as a country “which imposes a low or no tax, and is used by corporations to avoid tax which otherwise would be payable in a high-tax country.” According to OECD, tax havens also exhibit a lack of transparency and effective exchange of information in the operation of their legislative, legal or administrative provisions – especially important to investors who wish to avoid public scrutiny.

Tax havens, explains Aston Business School’s Chris Jones, are “offshore” financial centers that allow multinational enterprises and high net-worth individuals to channel international capital flows out of high tax jurisdictions into low tax jurisdictions. In the context of multinational enterprises, he says, this often results in profits being shifted in order to avoid corporate tax.

“What these tax havens do is to take advantage of differences in the tax and legal code between countries to encourage inward capital flows,” Jones told Mongabay.

The typical tax haven business model is simple and, most notably, legal. Firstly, it sets a low corporate tax rate on foreign capital inflows and a level of secrecy that makes it difficult for revenue authorities to track payments down. The tax haven collects fees and royalties from the capital flows, in order to finance economic development.

“However, very often there is a high level of inequality within the tax haven jurisdictions, and the indigenous population doesn’t reap the proceeds of this development strategy. Hence, one might view tax havens as parasites that undermine the capitalist system,” Jones said.

Tax havens linked to the Brazilian Amazon

The researchers focused on the nine largest companies operating in the beef and soy sectors of the Brazilian Amazon – agribusiness activities widely recognized as key drivers of deforestation. The firms selected that were involved with beef production included Bertin, JBS, Marfrig, and Minerva, four companies that alone represented 33 percent of total slaughter capacity in Brazil in 2006, and 38 percent in 2009. Their selection of soy producers included transnationals Bunge, Cargill, Archer Daniels Midland, Louis Dreyfus, and Brazil’s Amaggi, which together owned 48 percent of all the installed soy crushing capacity in Brazil over the period 1999-2009.

The findings showed that a total of US$26.9 billion in foreign capital was transferred to these nine companies between October 2000 and August 2011. 68 percent of this amount – about US$18.4 billion – was transferred from tax havens, but this is an average figure. For example, Bunge received US$6.9 billion from its own subsidiaries registered in the Cayman Islands as cash in advance, representing 90 percent of the total foreign capital received by that company between October 2000 and August 2011. ADM received virtually 100 percent of its foreign loans (about US$1.7 billion, representing 62.4 percent of the total foreign capital it received) from its own subsidiaries, also located in the Cayman Islands.The lion’s share of these billions flows through the Cayman Islands for a reason: it is a British overseas territory with strong links to the UK and in particular the City of London, a well-connected economic powerhouse. Today, these little Caribbean islands do far more business than their tiny population warrants, and the Caymans is one of the world’s largest financial centers: not only because investors enjoy its legal efficiencies, but also due to tax-minimization (in many cases zero taxes and low fees), as well as a high degree of secrecy.

Jones points out that tax havens are competitive with one another, and very often specialize in particular areas. “Hence, Cayman has a tendency to specialize in banking and hedge fund formation and this has evolved to form a major cluster of financial activity that helps ‘grease the wheels’ of what many might regard as illicit financial flows that are channeled through the financial system,” he said.

The secrecy and lack of transparency found in Cayman Island and other tax havens appear to be very important to those investing large sums in agribusiness companies responsible for significant Amazon deforestation, likely because these investors do not wish their activities to be exposed to a critical public or to environmental NGOs.

Hard to trace cash flows that enable deforestation

Galaz and his team stress that in today’s largely deregulated financial atmosphere it is impossible to assess how the financial capital flowing into Brazil-located agribusiness companies via tax havens is distributed across their operations. For this reason, it is very difficult to quantify and establish direct causality between financial transfers via tax havens and actual land-use change in the Amazon. However, Galaz says, what we can say for certain from previous research is that soy and beef producers are strongly associated with Amazon deforestation, and that access to large amounts of foreign capital helps allow for that deforestation.

“The commodity chains are quite complex of course, but simply put, economic activities on the ground need capital to be able to operate, and we find it interesting, and worth discussing, that a lot of this capital is transferred from subsidiaries located in tax haven jurisdictions,” Galaz said.

Though some of the companies replied to the researchers’ request to respond to the study results presented in the Nature article ahead of its publication, only two replied to Mongabay’s invitations to comment for this article. Most notably, none answered questions about how much money flowing through a tax haven was used to finance operations in the Amazon, or if the loss of tax revenue resulting from the use of tax havens should be considered as indirect subsidies to increase land-use change.

Susan Burns, Bunge’s Global Media Relations & Agribusiness Communications’ Director, points out that Bunge has been a public company since 2001, with tax information disclosed in detail in their public filings. “As for the Amazon, Bunge has participated in the [voluntary Amazon] Soy Moratorium since its inception in 2006,” she told Mongabay, stressing that her company has a zero-deforestation commitment for all of its supply chains, which aligns with a public strategy to achieve that goal.

Minerva Foods responded to Mongabay’s enquiries with the following statement: “Minerva products are associated neither with child/forced labor and embargoed areas nor with illegally deforested areas in the Amazon biome and encroachment on Indigenous Lands, Conservations Units and Environmental Protection Areas.” The statements also point out that all Minerva’s suppliers are checked for sustainable criteria in Brazil, both inside and outside the Amazon biome.

Tax havens and ocean harm

According to the UN, illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing is “one of the greatest threats to fish stocks and marine ecosystems and continues to have serious and major implications for the conservation and management of ocean resources, as well as the food security and the economies of many States, particularly developing States.”

That being so, the Nature study dived into the fisheries industry to shed light on the relationship between IUU fishing and tax havens. Team researchers found that while only 4 percent of all fishing vessels globally are flagged in tax havens, the figure jumps to 70 percent when considering vessels involved in IUU fishing.

This suggests that companies that engage in IUU activities benefit from the use of tax haven for both tax purposes and also as a means of aiding obfuscation of ownership and vessel identities.

According to the study, IUU fishing and tax havens are linked in many ways. First of all, these jurisdictions allow for aggressive tax evasion. Moreover, many tax haven nations are also flags of convenience (FOC) states.

According to the International Transport Worker’s Federation, an FOC ship is one that flies the flag of a nation that is other than the country of ownership because the FOC state offers minimal regulation, cheap registration fees, low or no taxes, and freedom to employ cheap labor. As a result, “flagging out” owners expect limited or no sanctions when operating in violation to international law.

“Owners may therefore register vessels in open registries to avoid compliance with more robust and heavily enforced regulation in their own country,” said Baptiste Jouffray, who conducted the fisheries analysis for the study.

A striking example, Jouffray says, is the case of Vidal Armadores, a Galician company that over the period of a decade allegedly used a network of screen companies in jurisdictions such as Panama to hide beneficiary owners and reduce the risks for vessels guilty of IUU fishing being apprehended.

The secrecy offered by combined use of tax havens and FOCs also allows companies to secure a dual identity for a fishing vessel – one used for legal, and the other for illegal fishing activities. Put simply, the use of tax havens and FOCs makes the tracing of fisheries resources and accountability extremely difficult and costly for regulators.

This is why the researchers see these legal and economic dodges as a major threat to the global ocean resource sustainability.

Jouffray stresses that “by obfuscating profits and beneficiary ownership, tax havens facilitate the evasion of regulations aimed at sustainably managing fish stock” including regulated quotas, and he notes that “while direct causality will always remain elusive, there is a need to put tax havens on the ocean sustainability agenda.”

The need to close the tax haven loophole

The new study has some limitations, agree researchers, imposed by the secrecy of interactions between global financial and production networks, and also due to the lack of available data. The team notes, for example, that it was only able able to access official figures from the Central Bank of Brazil from October 2000 to August 2011, because the transparency resulting from the legal requirements for the publication of transfers of foreign capital introduced in October 2000, was suspended in August 2011.

“This means we have no data after that date (although this may change in the future), and we can’t say anything about the recent links between tax havens and the Amazon. We can only look at historical examples,” explained Alice Dauriach, research assistant at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences’ Global Economic Dynamics and the Biosphere Programme.

However, Jouffray asserts that the recent research underlines the urgency for adding an environmental dimension to the international debate over tax havens, and especially adding it to the agenda in order to reach United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

“Any amount [of money] invested in sectors whose operations cause deforestation may be financing the destruction of forests,” said Màrcio Astrini, Greenpeace Brazil’s Public Policy Coordinator. In the case of tax havens, he says, the mere existence of doubt and a lack of transparency is already an unacceptable environmental danger.

“To imagine that fiscal pardons can finance environmental crime, the destruction of natural resources, and increase social scourges such as land conflicts and slave labor, usually associated with deforestation, is unacceptable,” he concluded.

The researchers also urge that leading international organizations – the Group of Twenty, UN Environment, the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, and the UN Office of Drugs and Crime –carry on joint independent assessments of natural capital costs, looking at loss of biodiversity and carbon sequestration, and the loss of tax revenue through the use of tax haven jurisdictions.

“This assessment should help reduce uncertainties around causality between capital flows and environmental change and include a more comprehensive set of biomes, economic sectors and companies and their subsidiaries than presented,” concludes the study.

In this regard, Joy Aeree Kim, UN Environment’s Senior Economic Affairs Officer, noted that the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), hosted by UN Environment, is already looking at tax havens. TEEB is a global initiative focused on “making nature’s values visible” with an objective of mainstreaming the value of biodiversity and ecosystem services within decision-making at all levels.

Greenpeace Brazil’s Astrini believes that an environmental impact assessment needs to accompany all major investments, ranging from those by local and national governments to global capital flows, and that the findings should be transparent and accessible.

“There are no diplomatic efforts or international agreements that will be able to change the [destructive] direction of climate change if investments flow in the opposite direction,” he said, emphasizing that those who finance deforestation or a coal plant have a responsibility for the effects that a warmer planet brings, affecting primarily the poorest and most vulnerable populations.

Ultimately, Astrini sees transparency as a moral obligation. “People” he said, “have the right to know which companies and investors are helping to solve the climate problem or make it worse.”