The Nation| 17 September 2018

Chinese investors shift agriculture practices in North

By JINTANA PANYAARVUDH

TWO YEARS ago, Prasat Prueangwichahorn, a Thai driver in a Chinese banana plantation in Laos, saw a business opportunity when Laos ordered a ban on new banana plantations out of concerns for the environment and workers.

He brought some seedlings of Chinese Cavendish bananas, or kluay hom kheaw, to his hometown in Phayao’s Chun district and found that they flourished. So, he leased a 200-rai (32-hectare) plot from villagers and started his own plantation, called “Huay Kieng”.

“I was lucky to have worked in a ‘safe’ agricultural zone in Laos, and learned many things, especially how to grow fruit without using dangerous chemicals,” he explained.

Over the past two years, Chinese investors appear to have invaded provinces in the North, such as Chiang Rai and Phayao, to grow Cavendish bananas after the practice was banned in Laos.

Locals and NGOs, however, have voiced concerns about Chinese-run plantations using pesticides excessively and giving rise to conflicts over water.

Cavendish bananas are widely consumed in China because it is said to be good for health. And thanks to the seven years he spent in Laos, Prasat built connections with Chinese businessmen and now exports the fruit to China, Vietnam and the Middle East.

He sends off some five containers, or a total of 100 tonnes, every eight months to the three countries. His income before expenses per container is about Bt1 million.

Prasat said this business would do even better if Chinese investors could take over large tracts of land and allow plantations to be controlled by Thais.

“But it’s hard to do that in the North, because the land is divided into small plots for villagers,” he explained, adding that sometimes it is difficult to meet all the orders. This why, he said, he decided to go into contract farming, following Chinese investors’ practices with hilltribes such as Hmong, Man and Yao living on the border with Laos.

Prasat sells banana saplings to his luk rai, or contract farmers, and teaches them how to get a good harvest of top quality fruit. He also finds them foreign buyers.

“I don’t take any commission or profit, but if both sides are generous they give me something,” he said, though he does sometimes struggle when contract farmers fail to pay him for the saplings.

Chinese influence

Though Prasat appears to be setting a good example by not using too many chemicals in his plantation, the Chinese-run farms are still posing big concerns in terms of environment, labour and farmers.

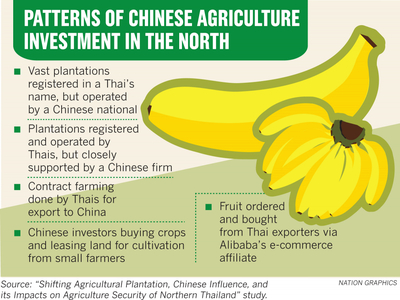

Contract farming for Cavendish bananas began in the North of Thailand two years ago, according to an ongoing study titled “Shifting Agricultural Plantation, Chinese Influence, and its Impacts on the Agriculture Security of Northern Thailand”.

Due to the Chinese-driven boom and expansion of the export market, fruit growers in the North had to adjust to contract farming, Chiang Mai University Sociology and Anthropology lecturer Panitda Saiyarod, who is leading the study, said.

Under this system, small-scale Thai firms act like investors and sell banana seedlings to contract farmers, and provide them with advice and farming techniques until the fruit can be harvested.

However, since China has strict quality controls in terms of size and weight, inexperienced Thai growers face the risk of their crop being rejected, the researcher said. Supported by the Thailand Research Fund, the study also found that Chinese investors preferred to own and operate huge banana plantations.

“Chinese investors invest in large plantations in other countries, because there they can have full control on the management and ensure highest production,” Panitda said.

This pattern of investment was found in Chiang Rai, where a 2,700-rai banana plantation has been leased by Phaya Mengrai Agriculture Limited Partnership. The firm is owned by Chinese-Thai investors, with the lion’s share of the firm held by locals, as Thai law does not allow foreigners to majority own or lease land for commercial agricultural purposes.

Another interesting finding is the higher incentive offered to workers. Chinese-owned plantations pay as much as Bt300 a day to labourers, but a major share of the work is taken over by migrant workers, affecting the bargaining power of local labourers.

Panitda raised concerns about workers’ rights being abused and the lack of proper healthcare benefits. She also pointed out that measures to protect the environment were still weak. Hence, she said, the authorities should screen all foreign investors and strictly enforce public land laws to ensure resources are fairly shared between big business owners and communities.

Her study also learned that Thai agricultural goods exporters relied heavily on China, and that the mainland is one of the biggest buyers of bananas from Thailand. Though statistics show a continuous increase in exports from 2014 to 2017, the value of banana exports last year alone rose to 48.82 per cent to around Bt350 million. These figures were released by the Information and Communication Technology Centre of the Office of the Permanent Secretary Ministry of Commerce as well as the Customs Department.

“But with volatile cultivation prices, farmers are earning less and their debts could rise. This will certainly affect their lives in the future,” she concluded.