Front Line Defenders new report identifies the root causes of violence in Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico and the Philippines, where more than 80% of the human rights defenders killed globally over the last four years were murdered.

'I ran away but she sat there... Then they smiled and shot her'

BRAZIL, COLOMBIA, GUATEMALA, Honduras, Mexico and the Philippines. More than 80% of the human rights defenders (HRDs) killed globally over the last four years were murdered in these countries.

The vast majority of the cases have never been properly investigated, and few perpetrators have been brought to justice.

In 2016, Front Line Defenders launched the HRD Memorial to document the cases of the estimated 3,500 HRDs who have been killed since the United Nations Declaration on HRDs came into effect 20 years ago.

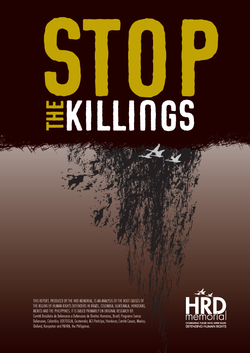

This research has provided the basis for a new report, Stop the Killings, which identifies the root causes of the violence common to all six countries: the power of entrenched elites who are resistant to change; legal systems co-opted by organised crime and corporate interests; the collusion of the State and/or its agents but above all a fundamental lack of political will to address the issue.

Three weeks ago I travelled to Guatemala as part of an international delegation in response to a call for help from local communities under siege by large landowners, mining firms and hydro-electric companies who want to control the land and the water.

In Guatemala, 74% of the land is owned by 6% of the people. Every single river in the country has been concessioned for private hydro-electric schemes and peasant communities have been forcibly evicted to make way for vast estates of African palm (grown to produce palm oil), rubber and sugar.

Since January 2018, 19 HRDs have been killed in Guatemala, nine of them from CODECA, an organisation that campaigns to protect the land rights of peasant and indigenous communities. CODECA has strong leaders, is well organised and can mobilise nationally. Its members are therefore a threat – and a target.

The community of Aldea Verde has been evicted four times since the 1990s, including in recent weeks. Its members keep trying to return to their traditional lands.

One of them, Dona Juana, described to me how her husband (who had received multiple threats) went out to buy food for the family and was later found dead on the road.

Four other members of the community have been killed since then.

Sugar fields

There are other life and death issues. Independent farmers who have either been evicted from their own land or whose farms cannot compete with agricultural corporations have no choice but to work in the sugar fields.

Sugar cane is harvested first by burning and then cutting it, creating a toxic mix of soot and chemical residue. The conditions are so inhuman that anabolic steroids (given to horses in the United States), are added to the workers’ food to give them the strength to endure their task.

As a result, the area has the highest level of renal failure in the region and few of these workers live beyond 40.

As one man said, “They have taken everything from us – even our fear, so we have no choice but to continue the struggle to defend our rights.”

Yet in demanding their rights, these people are considered obstacles to development and made enemies of the state.

In Brazil, the territories of indigenous peoples are usurped by land grabbers, farmers and by the State itself.

In 2016 alone, 196 incidents of violence against rural communities were reported. The indigenous peoples of Brazil and their leaders are more at risk now than at any time in their recent history.

On 24 May 2017, 10 rural workers were killed in the municipality of Pau d’Arco, in Pará state, during an operation by the military and civil police.

Among the dead was Jane Júlia de Almeida, leader of the camp and the only woman murdered that day. Jane had suggested that the group stay where they were when the operation began, believing the police would not come looking for them in the rain.

But she was wrong.

According to a witness, “As the group stood under a tarpaulin waiting for the rain to stop the police arrived shooting as they ran, shouting that everyone was going to die.

I ran away but she sat there. I do not know if they killed her sitting down, I just remember they were saying: ‘Get up to die old bastard, old slut, bitch.’ Then they smiled and shot her.

PastedImage-66255 Jane Júlia de Almeida

During an Indigenous Peoples’ Summit in Davao City in the Philippines on 1 February 2018, President Duterte stated that Lumads (indigenous peoples of the Philippines) should leave their ancestral domains as he would broker investors to invest in these lands: “We’ll start now, and tomorrow I will give something to you. Prepare yourselves for relocation” was his cryptic warning.

In one incident in December 2017, eight Lumad people were killed in what was initially presented as an armed confrontation with the army.

The main target of the attack was Victor Danyan, chairman of Tamasco, a tribal group formed in 2006 to reclaim 1,700-hectares of ancestral land.

Forensic expert Dr Benito Molino was able to discredit claims by the army that they were attacked by members of the Lumad community. According to his evidence, “There was no clash – all the shooting came from the army.”

In all these cases the single unifying factor, apart from the sheer brutality of the killings, is the lack of any political will to do anything about it both nationally and internationally.

In the Philippines, President Duterte has declared open season on HRDs: in Colombia, more HRDs are being killed than during the actual conflict (90 so far this year) and in Honduras student leaders are routinely kidnapped by “alleged” police and later found dead on the side of the road.

Meanwhile President Morales of Guatemala has shut down the UN-backed Commission Against Corruption and Impunity in what in is effect a pre-emptive strike to protect himself from charges of prosecution for corruption.

The only active agents for change are the HRDs working for justice and human rights. Their support and protection must be an urgent international priority.

Jim Loughran is head of the HRD Memorial Project with Front Line Defenders.