GRAIN | 6 June 2018

Failed farmland deals: a growing legacy of disaster and pain

"The project seems ‘failed’ from the outside, but there's a need to keep up the pressure and demand that the land be returned to the people − not just for the company to pull out their investment."

Premrudee "Eang" Daoroung of Project Sevana, Thailand, reflecting on Mitr Pohl’s sugar plantation in Cambodia [1]

2017 went down as one of the deadliest years ever for land defenders. [2] It was also a pretty bad year for several land grabbers. A significant number of big farmland deals collapsed, adding to a growing list of projects that have backfired over the past few years. While this is good news for affected communities, many of them are now left dealing with the fall-out and still struggling to get their lands back. We may have made some gains in stopping the projects, but have urgent work to do to address what happens when they fail. [3]

Takeaways:

- GRAIN has documented at least 135 farmland deals for food crop production that have backfired between 2007 and 2017. They represent 17.5 million hectares, almost the size of Uruguay!

- These are not failed land grabs, since the land almost never goes back to the communities, but failed agribusiness projects.

- While higher standards of due diligence and stronger forms of liability are surely needed, the real challenge is to get the land back to the communities. No one should rest until that is achieved!

- The enormity and number of these failed farmland deals tell us that they should never have been allowed to happen in the first place. Investment is needed in policies and initiatives to support food production by local communities, not opening the doors to agribusiness.

What we are seeing

When GRAIN last updated its database of land deals in the food and agricultural sector, we identified 135 deals covering 13 million hectares that had been cancelled or abandoned or seemed to have disappeared or collapsed. We put these in a separate table, outside our field of vision. That was in 2016.

In 2017, we were struck by the number and importance of failed farmland deals that were being announced. Many of them were emblematic projects that had made global headlines or captured imaginations earlier on. The Indian agribusiness investor Karuturi proclaimed he was leaving Ethiopia. The French government announced its decision to pull out of the G8 New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition (NAFSAN). The president of Senegal told Anas Sefrioui, Morocco’s third richest billionaire, who got a 10,000 ha concession to produce rice in Dodel, the deal was off. We wondered if we should celebrate but decided instead to take stock of what was going on and what it meant. In that process, we consulted allies and partners for their views. [4]

Looking at the hard data available, several comments can be made: [5]

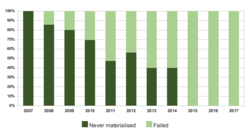

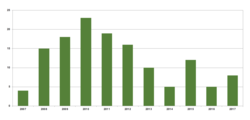

- For the decade spanning 2007-2017, we have trustworthy information on 135 land deals intended for food crop production that backfired for one reason or another (see figure 1). They represent a massive 17.5 million hectares, almost the entire land area of Uruguay.

- Failed land grabs for agricultural production peaked in 2010, but they are on the rise again since 2015.

- We found no geographic pattern nor specific pattern in terms of the investors themselves.

- The failures have clearly shifted over time from deals that never actually materialised (no farm production took place) to projects that failed (see figure 2).

What we bundle under the term “failed” deals covers different realities. In some cases, investors lost their land because the government cancelled or severely scaled back a permit or concession, as happened to Herakles in Cameroon. In others, investors pulled out because they were losing money or facing other negative consequences, such as with the Italian Tampieri Group's Senhuile project in Senegal. Other cases can be classed as failures because there is so much grassroots opposition to them that they are blocked or stalled. Further cases fall in this category because they are not meeting expectations. In yet other cases, the investor went bankrupt.

One aspect that is extremely important to stress is that these are not failed farmland deals in the sense that the land has gone back to the communities who were there before. On the contrary. The projects are often passed on to other investors or to the state. In that sense, the land grabbing itself does not fail! It is the investors and their projects that fail. That is why we do not talk about failed farmland grabs, but failed farmland deals. We cannot emphasise this enough.

Why are so many farmland deals failing?

The case of the World Bank’s PDIDAS project in Senegal offers an important insight into the recent failure of some of the farmland deals and projects. The acronym PDIDAS stands for "Inclusive and sustainable agribusiness development project" in French. It was launched in 2014 for a five-year period, with a loan of $80 million from the World Bank. The idea was to promote big commercial export-oriented farm operations in Senegal without wiping out small farmers and herders who are the backbone of the country's economy. Foreign investors, like domestic ones, would get access to land that would be divided 50:50 between their companies and surrounding family farmers. This way, infrastructure developed for the project (roads, irrigation, electricity, fencing, etc.) would be available to and used by all.

In essence, the project aimed to set up parallel tracks of agricultural “development”, big business alongside family farming, in a fiercely ideological drive to demonstrate that we shouldn't have one without the other. The investors would be free to produce their own crops for export or contract out production to the small farmers. In the process, certain elements of Senegal's land law would be skirted to permit the leasing of lands to both the investors and the communities without making changes to it, maybe even providing a new “model” for the land reform process then under way.

So much for the theory.

In reality, the project was and is a flop, groups in Senegal say. According to Ardo Sow, a civil society activist who hails from the project area, of the 20,000 hectares identified and made available for the project, only 200 ha (the pilot site itself) had been developed and put into production as of early 2018. [6] Why? Local mayors say the project got stuck in its own rigidity, bureaucracy and lack of clarity. "Zero benefit," they cry. "Dysfunctional", others say. "Unsatisfactory", the World Bank puts it, knowing that when the project ends in 2019 there won’t be much to show for it. [7] And yet, as Sow points out, Senegalese tax payers will have to pay back the loan.

The fundamental flaw with PDIDAS is that its overall plan to push consensual agribusiness as a strategy is and was oriented towards making things work for the investors, by winning over local communities. The idea is not to strengthen peasant farming, but to move agribusiness forward, internalising peace-building with communities who have been living on the land for generations and who are reluctant to cede their lands to agribusiness. Ultimately this also explains the collapse of the ambitious Nacala Corridor Fund, that was supposed to generate multiple agribusiness projects between foreign companies and small farmers in northern Mozambique, and the G8's NAFSAN in Africa. Both sought to impose agribusiness blueprints onto the realities of African peasants.

Another factor in the failure of many deals is the incompetence of the companies. Often the businessmen (yes, men) behind the projects have little to no experience in agriculture and little knowledge of the places where they've acquired farmlands. Karuturi's farmland deal in Ethiopia is one emblematic case (see box on Karuturi: the neverending pendulum). Calvin Burgess, a businessman from the United States who made his fortune in private prisons, failed badly with his large-scale rice farming endeavours in Kenya and later Nigeria, known as Dominion Farms. Several major ventures financed by Saudi business groups have also flopped, such as the Foras 7x7 programme that was supposed to convert 700,000 hectares of land across West Africa into rice plantations or the Arafco sugar cane project in Kenya, backed by a Saudi prince, which has gone nowhere and is now under investigation by Kenya's anti-graft commission. [8] And there's also the oil palm plantation empire that Indian IT billionaire Sivasankaran amassed in a few years, stretching from Papua New Guinea to West Africa. All of his plantation projects, which add up to over 500,000 ha, have been at a standstill since he filed for bankruptcy in the Seychelles in August 2014. [9]

A final, key factor that cannot be overlooked in explaining the growing number of failed farmland deals is the opposition to them. Local resistance movements have challenged and helped numerous land deals to stall, fail or be revamped. This is clear in many cases and needs to be recognised. In Cameroon, the Herakles land concession was downsized to a quarter of its original scale due to intense campaigning from community organisations and NGOs in the country supported by international groups. In Senegal, persistent pressure at the local level buttressed by research from international allies helped castrate the Senhuile project which is still there, sort of, but in a severely shrunk form. [10] In Mozambique, strong resistance from peasant organisations backed by Japanese and Brazilian colleagues has put the trilateral Prosavana project on life support and killed off its foreign investment component, the Nacala Corridor Fund. In Argentina, it was massive social resistance that stopped Beidahuang, a huge Chinese agribusiness group, from getting 320,000 ha in Rio Negro. Just like what happened in Madagascar against Daewoo, who tried to get 1.3 million ha of the country’s farmland.

More recently, it was the people's resistance in Dodel that brought about the cancellation of the Afripartners project in Senegal. It was intense pressure by French NGOs together with outcries from African colleagues that brought the French government to question and pull out of the G8 New Alliance, based on risks it came to understand about land grabbing. Large NGO campaigns have succeeded in stopping sugar producer Mitr Phol in Cambodia or Cargill in Colombia, while persistent community organising helped drive Dominion Farms out of Kenya.

In Mali, grassroots leaders point out that a failed land deal like the Malibya project, although it did not fall apart because of local resistance, helped ignite a movement of popular resistance that is now a powerful social force in the country and that has influenced a rewrite of the national land law.

What can we learn from these failed deals to stop others?

The failure of so many farmland deals makes it obvious that governments are not doing their job to properly screen would-be investors. Fraud, including false claims about investors' abilities to engage in agribusiness, abounds. These days, all companies claim to have some sort of standard for responsible investing but this rarely seems to matter, as internal standards are often violated by companies acquiring farmlands. [11]

This makes due diligence by host states and requirements for investors to actually cultivate the land more necessary than ever. The problem, though, is that due diligence in many cases goes no further than a superficial check of the Internet to see that no red flags appear. Civil society groups and journalists are often doing more to catch corruption involved in land deals than the authorities. And this is a problem everywhere -- including in Australia, France, the US and Canada, where foreign companies are acquiring farmlands with hardly any oversight and often totally under the radar.

We need to use this accumulated evidence of failed deals to press more urgently for moratoriums, bans or stricter controls on the acquisition of farmlands by foreign companies, and even domestic companies. This is not easy work. Some governments refuse to budge from their land investment policies, even in the face of numerous failed deals, mass opposition and violent conflicts, such as in Ethiopia, Papua New Guinea and Cambodia (see box on Land grabbing as state policy is also a failure).

Another important take away is the need to hold companies and their investors accountable. Companies and governments make all kinds of promises to communities to get them to give up their lands -- jobs, schools, health clinics, etc. When projects collapse and fail to deliver on those promises, the communities rarely get their lands back and are not compensated for what they were supposed to receive. The Addax case in Sierra Leone is one clear example, but there are many others (see box on Addax).

Some of the groups involved in the struggle against the Addax project argue that it's not enough for investors to express commitment to or prove compliance with this or that standard, be it the International Finance Corporation’s performance standards or the UN Committee on Food Security’s voluntary guidelines on land tenure, to name the two most respected ones. Actual funding needs to be set aside for possible failure, as a part of a serious “exit strategy”, they say. Money is not the answer, of course, but the material needs of the communities who were left worse off because of the project cannot be ignored.

This is true. But a perhaps larger problem demonstrated by the Addax case is that, in the end, no one was held responsible. There was no actionable liability held by either Addax or the development finance institutions to remedy the situation that arose as a result of the project backfiring. This cannot be. We need investors, public or private, to be legally responsible for their failures.

As it stands, such remedies only exist for the companies, who can sue governments under provisions of bilateral or multilateral trade and investment treaties when their projects fail (see box on ISDS). This is a backwards and fundamentally unjust situation that must be urgently reversed.

But perhaps the most important message is that these and other farmland deals should never have been allowed to happen in the first place. Investment is needed in policies and initiatives to support food production by local communities, not opening the doors to agribusiness.

What do we do when projects fail?

As we've already underlined, when farmland deals fail, the land does not necessarily go back to the communities. It would be wrong to assume that as soon as a deal is cancelled or abandoned, the land is returned to those who were there before the investor came. This rarely happens and is a big part of the overall problem of farmland investing in general.

In numerous cases, the initial company is replaced by another, often without the community's knowledge. This company can be worse than the first and it may refuse to honour engagements that the initial company made to the communities. Concessions can also be reallocated or sold to new companies. In other cases, states take back the land for other uses. It is even possible that that company has only temporarily left the scene, waiting in the shadows for a better time to restart the project.

Whatever the case, the aftermath of a failed farmland deal is usually devastating for communities. Even if they do get back some of their lands, these lands have likely been deforested or exhausted, and traditional sources of water may no longer exist. This makes it hard for them to farm, hunt and harvest as they once did to ensure their food and livelihood needs. There may also be lingering social tensions between those in the community who fought against the project and those who accepted it.

The communities may also find themselves suddenly isolated, without the national and international support networks they had when they were struggling against the project or the initial investor.

The failure of a farmland deal is not a time to relax. For the alliance of groups that opposed the project, it is a time to ramp up the work, and shift to a new phase. The focus now has to be on supporting the affected communities to get their lands back and to restore them to suitable conditions. The land grabbers and their financial backers need to be held liable for the damages, and this requires creative strategies and on-going support from allies, at home and abroad.

It is also important to recognise that leaders from communities that have stopped land deals have valuable experiences that need to be shared with other communities. These leaders should be encouraged and supported to participate in movements against land grabbing, especially at the national and regional levels. Greater awareness and stronger unity among communities is the most important defence against future land grabs.

Going further

- GRAIN has published datasets on agricultural land grabs in 2008, 2012 and 2016.

- The open-publishing website http://farmlandgrab.org tracks land deals for agricultural production.

- The open-publishing ISDS platform has a special section on investor-state dispute settlement and land rights: http://isds.bilaterals.org/?-land-rights-

Land grabbing as state policy is also a failure

Cambodia's Land Law of 2001 allows the state to` grant economic land concessions (ELCs) on private state land for the purpose of industrial agriculture and large-scale plantations (teak, rubber, sugar cane, etc.). ELCs are long-term leases. They provide domestic or foreign companies exclusive rights to clear and use large tracts of farmland for up to 99 years. One ELC cannot exceed 10,000 hectares and no one company can hold ELCs totalling over 10,000 ha. The stated goal of Cambodia's ELC programme is to sustain economic growth and accelerate the reduction of poverty. For communities in Cambodia and NGOs working with them, the ELC policy has driven land grabbing and not fulfilled its promises at all. In their eyes, the policy itself is a failure.

Human rights lawyers would agree. That is why they have filed a case arguing for the opening of an investigation against the Cambodian state for land grabbing at the International Criminal Court in The Hague. The ICC has determined that systematic state practices leading to land grabbing can be examined by the court. Cambodia is one good candidate. Ethiopia and Papua New Guinea could be others. [12]

There is no central set of figures, but by 2012 more than 11% of the country's land area had been given away through ELCs. [13] As a result, a moratorium on new concessions was declared, while the government committed to review past concessions. Yet not much has changed. In fact, at least 10 more ELCs have been granted since the moratorium began.

The state's response to the outcry has been to speed up its equally failed titling programme. Earlier efforts to give out titles, heavily funded by the World Bank, resulted in more than a million land documents granted but arbitrarily and far from concessions, thereby not affecting the large land holdings at all. This created more insecurity and inequality for rural communities, not less.

In 2016, the government declared that the review conducted during the moratorium was a success as it had identified 1 million hectares that will be reassigned to local communities. But no one knows where these lands are and who is in charge.

According to Ang Cheatlom, the head of Ponlok Khmer, a community organisation in Preah Vihear province, “Only those who had land certificates in the former ELC areas can get their land back. But the majority of people do not have land certificates. So the land will be reallocated to the state who will do what it want with it. This is why the land conflict in Cambodia is never ending.” [14]

Investor-state dispute settlement and land grabbing: how does it work?

Most free trade agreements and bilateral investment treaties provide special protections to foreign investors, mostly to attract companies that bring capital, infrastructure and jobs. These protections affect land rights in at least two important ways.

First, in terms of principles, these treaties tend to assert that foreign investors should not be discriminated against, simply because of nationality. This will override any national law or constitutional provision that bars foreigners from owning land, including farmland. This is a serious issue in many countries. Many Eastern European countries prohibited foreigners from owning land but, in theory, had to drop that to join the European Union. In reality, they are still struggling with this. In other countries, such as Thailand or the Philippines, constitutions ban foreign ownership and investors can only lease or rent. Even where leasing is the process, some governments limit this, like in Brazil or Australia. These trade deals also grant foreigner investors protection against expropriation. Land rights are a formidable type of property and any move to withdraw or limit them can be considered expropriation if taken to the courts.

Second is, yes, the courts. Many trade and investment agreements give investors the right to sue foreign governments for unlimited damages if their expectations of a profit are undercut. This may arise because legislators adopt a new law (e.g. limiting their right to accumulate land) or because an authority moves to take property from them (e.g. withdrawing a land lease or permit to cultivate). This provision is called investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) and has become the lightning rod of public interest campaigns to stop trade deals in the past few years. ISDS is especially criticised because foreign companies get rights that domestic companies do not, and legal proceedings are carried out not in actual courts but through arbitration. Worse, the awards granted to investors run into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Farmland investors have taken governments to court under ISDS provisions and continue to do so. (A few cases are highlighted below). The message should be clear. It is important to ensure that governments have free rein to restrict any investor's rights to farmland and that such privileges granted to foreign investors under trade and investment deals be removed.

Current ISDS cases involving farmland investments:

- SunLodges Ltd. and Sunlodges (T) Ltd. (Italy) vs Tanzania, claiming US$ 30 million + interest

- Agro EcoEnergy Tanzania and Bagamoyo EcoEnergy Limited (Tanzania) and EcoDevelopment in Europe AB and EcoEnergy Africa AB (Sweden) vs Tanzania

- Magyar Farming Company Ltd (UK) vs Hungary (500 ha under potato and dairy farming)

- Grot and others (US, Poland) v. Moldova (pending)

Past ISDS cases involving farmland investments:

- Vestey Group Ltd (UK) vs Venezuela (cattle farm of 290,000 ha): US$ 98,145,325 awarded to investor

- Quadrant Pacific (Canada) v. Costa Rica (case discontinued)

- Almås (Norway) v. Poland (4,200 ha) (decided in favour of state)

- Von Pezold and others (Germany) v. Zimbabwe (decided in favour of investor)

- Bernardus (Netherlands) v. Zimbabwe (decided in favour of investor)

Karuturi: never ending pendulum

It’s impossible to talk about failed farmland deals and not talk about Karuturi. This Indian company, run by a man of the same name, made headlines in 2009 when it acquired land leases covering over 300,000 hectares of farmland in Ethiopia, mainly in the Gambela region. Karuturi boasted huge ambitions to become the Cargill of Africa and tried to get more land in countries like Tanzania and Nigeria. Karuturi did succeed in fencing off and ploughing up several thousand hectares in Gambela. In that process, his project uprooted many local indigenous communities who felt they were robbed of their lands, poorly compensated and barred access to food, water and their sources of livelihood. But he never managed to produce much, blaming it on Mother Nature.

By 2013, the government in Addis Ababa was getting impatient and threatened to withdraw Karuturi’s permit to operate. Like other governments, Ethiopia does have a policy of “use it or lose it”. If an investor acquires but does not farm the land productively within a period of time, the land concession is withdrawn and given to other investors. Karuturi threatened to sue the Ethiopian authorities through the investor protections afforded under MIGA of the World Bank or the investor-state dispute provisions of India-Ethiopia bilateral investment treaty. (See box on ISDS) As far as the public knows, Karuturi had no protection under MIGA, so he would have had to use the investment treaty or straight diplomatic pressure, none of which is in the public record. Whichever route he chose, in September 2017 Karuturi boldly announced that he was recognising his defeat and leaving Ethiopia.

Would the affected communities now get their lands back? Could those who had taken refuge in Kenya finally return to Gambela? To everyone's great shock, a few months later, in April 2018, the pendulum swung again and Karuturi announced that he managed to renegotiate a new lease, presumably with the new government, for 25,000 ha. It is hard to understand how a completely failed project such as Karuturi’s can be awarded a new lease – especially at the expenses of local communities who could have expected more from the new government. [15]

Addax: a disaster by any other name

In 2010, spurred by the biofuels directive of the European Union, the Swiss-based Addax & Oryx Group signed a memorandum with the government of Sierra Leone to lease 10,000 ha for an initial 50 years near Makeni, in the north of the country, to grow sugar cane. The cane would be processed into ethanol for export to the EU, while the residues would be converted into energy for Sierra Leone's electrical grid. Cultivation had already started and, by 2014, both ethanol and energy production began. The lease was soon after expanded to 57,000 ha. Development finance institutions (DFIs) from the UK, the Netherlands, Sweden, Germany, Belgium and Switzerland were brought in as co-financiers, and social programmes were set up to support the affected communities. It was supposed to be a showcase of sustainability and accountability. By mid-2015, however, operations were halted as overspending and allegedly poor harvests put the company in financial distress. By early 2016 the investors pulled out. Money was returned to the DFIs and the project was sold off to a murky British-Chinese consortium. In the process, 60 villages lost their lands, nearly 4,000 workers lost their jobs, hunger in the communities is now worse than before the project began and the Europeans got off scot-free. How did this disaster come about?

The project was marred with trouble from the start. Communities were not consulted and felt effectively robbed of their land. Only a portion of the promised employment materialised and villagers faced a double loss of food sources and clean water supply. Conflicts broke out, but were not properly resolved. By all accounts, poverty and misery grew as a result of this deal and little of the projected biofuel materialised.

When the investors pulled out, farmers were left dispossessed of their lands with no way to get them back. Sierra Leonean and European civil society groups that had been monitoring developments closely on the ground published several damning reports. [16] According to the development agencies Bread for All and Bread for the World:

"The DFIs suffered no damage and did not lose capital to continue to fulfil their mandate as their loans and equity were returned by the end of 2015. But the weakest actors in the project venture, the communities in whose name the project was co-financed, were ill-informed, unprepared for the discontinuation of operations and left in difficult livelihood situations." [17]

Annex

Footnotes

1 Personal communication with GRAIN, April 2018.

2 Matthew Taylor, “2017 on course to be deadliest on record for land defenders”, The Guardian, 11 October 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/oct/11/2017-deadliest-on-record-for-land-defenders-mining-logging

3 By “fail” we generally mean projects that are abandoned, withdrawn from, cancelled, suspended, scaled down or not performing.

4 Groups we consulted shall go unnamed, but we are very thankful to all of them! Many of their points are incorporated here.

5 Drawing from the data GRAIN has been compiling publicly through farmlandgrab.org, validated by direct contact with journalists and local groups.

6 Personal communication with GRAIN, 3 April 2018.

7 “PDIDAS : Entre tâtonnements, déceptions et contestations”, NDAR Infos, 27 September 2017, https://www.ndarinfo.com/PDIDAS-Entre-tatonnements-deceptions-et-contestations_a19998.html

8 Kinyuru Munuhe, “Mystery as Sh2b Malindi sugar ‘plant’ probe stalls”, Mediamax, Nairobi, 29 April 2016, http://www.mediamaxnetwork.co.ke/people-daily/217075/mystery-as-sh2b-malindi-sugar-plant-probe-stalls/

9 See GRAIN, “Feeding the one percent”, 7 October 2014, https://www.grain.org/e/5048 and Surajeet Das Gupta et al, “C Sivasankaran: Once the country's most astute deal maker, now a bankrupt entrepreneur”, Business Standard, 6 September 2014, http://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/c-sivasankaran-once-the-country-s-most-astute-deal-maker-now-a-bankrupt-entrepreneur-114090501264_1.html

10 In early 2018, it appears that the land has changed hands again from the Italians who handed it off to their Senegalese partner who has now passed it on to... Russians?

11 This has been particularly well documented in the case of the members of the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). See for example, Friends of the Earth Europe, “External concerns on the RSPO and ISP certification schemes”, 2018, http://www.foeeurope.org/sites/default/files/eu-us_trade_deal/2018/report_profundo_rspo_ispo_external_concerns_feb2018.pdf

12 Papua New Guinea’s “Special Agriculture and Business Leases” programme, as a state policy, could be considered a failure in itself. See Act Now PNG for more information: http://actnowpng.org/campaign/sabl

13 Open Development Cambodia has data accounting for 257 ELCs granted up to 2012, while the Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights has data on 274 ELCs covering 2.1 million ha.

14 Personal communication with GRAIN, March 2018.

15 For more on this, see Anywaa Survival Organisation, “It’s time to end land grabs and establish food sovereignty in Gambela”, May 2018, http://www.anywaasurvival.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/ASO_Report_May_2018.pdf

16 See in particular Swedwatch, "No business, no rights", 6 November 2017, http://www.swedwatch.org/en/regions/africa-south-of-the-sahara/swedfund-fmo-lacked-responsibility-leaving-project-without-exit-strategy/ and Brot für Alle & Brot für die Welt, "The weakest should not bear the risk – The case of Addax Bioethanol in Sierra Leone", September 2016, https://brotfueralle.ch/content/uploads/2017/07/1609_Addax_The-Weakest-Should-not-Bear-the-Risk.pdf

17 Brot für alle & Brot für die Welt, “The weakest should not bear the risk”, 2016, https://brotfueralle.ch/content/uploads/2016/06/The-Weakest-Should-not-Bear-the-Risk.pdf