By Carin Smaller, David Laborde

A trade war is looming between the United States and China. President Donald Trump has proposed tariffs on over 1,000 Chinese imports.

China has responded, saying it would impose duties on U.S. imports, including agricultural products. If they follow through, the resulting trade war would be disastrous—and not just for those two countries. What could it mean for global food security and the environment?

Let’s examine the case of soybeans, which China threatens to hit with a 25 per cent import tariff. Today, soybeans are a ubiquitous commodity in the global food chain. Seventy per cent of soy production goes to feed animals, particularly chickens, pigs and cows, as producers cater to the increased demand for meat from growing middle classes. The rest goes toward cooking oil, biodiesel, oleochemicals and other processed foods.

Agriculture and changes in land use already account for about a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions—a new wave of investment in soybean production outside the U.S. will lead to still more clearing of land, making matters worse.

The United States is the largest producer and exporter of soybeans, while China is the largest importer, importing two thirds of all U.S. exports. China cannot meet its own soybean demand because of limited agricultural land and stagnant yields. And yet its appetite for soybeans is immense: China imports close to 100 million metric tonnes annually—equivalent to 10,000 shipping containers per day. So what might happen if soybean imports from the United States are disrupted?

Such a move could unleash a major disruption of world markets reminiscent of the runup to the 2008 food price crisis—when the prices of rice, wheat and corn nearly doubled over a two-year period.

Shifts in China’s soybean supply typically have major market consequences. In March of this year alone, China purchased a third more soybeans from Brazil than a year earlier, driving up Brazilian soybean prices. If China replaces U.S. soybean imports with imports from other countries, their prices will rise. On the flip side, the U.S. could end up with a huge surplus of soybeans, driving down domestic prices and/or leading to dumping on other markets.

Historically, this type of disruption has had long-term impacts on the agricultural sectors of affected countries: When the Nixon administration implemented an embargo on soybean exports in the early 1970s, Brazil and Argentina expanded their production to fill the gap, triggering a trend that continues today.

More recently, the 2008 food price crisis triggered a global land rush. Many food-importing countries lost faith in the ability of world markets to reliably provide for their populations, and foreign and domestic investors acquired large tracts of farmland across Africa and Asia as a hedge against future uncertainty. A U.S.–China trade war could revive this unfortunate trend. China could be forced to search for new frontiers to secure its soybean demand and protect its supply chains, leading to another wave of so-called “land grabs.”

Indeed, China’s agricultural investments abroad have been growing steadily over the past decade, from USD 300 million in 2009 to USD 3.3 billion in 2016, most of it going to Asia (see chart below). Meanwhile, the Chinese chemicals giant ChemChina recently bought Swiss agrochemical giant Syngenta for CHF 43 billion.

If China and other countries expand global soybean production, that could exacerbate the negative environmental impacts of the global soy footprint. Soybeans are already a driver of deforestation in Brazil and Argentina. The area of land in South America devoted to soy more than tripled, from 17 million to 58 million hectares, between 1990 and 2015, mainly on land converted from natural ecosystems (FAOSTAT). Agriculture and changes in land use already account for about a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions—a new wave of investment in soybean production outside the U.S. will lead to still more clearing of land, making matters worse.

What can be done to head off disaster? First and foremost, a trade war must be averted at all costs. But there are other opportunities for action. Governments in Africa and Asia could now act on the lessons learned from the last wave of foreign land investment. Reforms have already been introduced in many countries to reform corrupt or insider-driven business practices, and better represent the interests of people and the environment. New land laws in Mali and Benin provide a durable solution to land tenure insecurity in rural communities. Laos introduced a temporary moratorium on land investments in order to conduct a comprehensive inventory of deals and improve the legal framework for foreign investment.

China cannot meet its own soybean demand because of limited agricultural land and stagnant yields

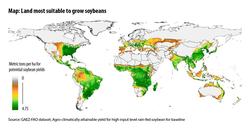

Indeed, as shown on the map below, several African countries could become the new frontier for soybean expansion, in particular in Central and Eastern Africa. This means that the new East African Community (EAC) model contract for farmland investments is highly relevant, as it strengthens the processes for managing environmental and social impacts, and for ensuring that women’s land rights are protected.

Finally, the threats posed by today’s trade tensions offer an opportunity to rethink current production and consumption patterns and reform food systems. For the sake of the environment and for global food security, meat and dairy consumption must be reduced in countries where the consumption is too high: essentially all industrialized countries. In addition, sustainable agricultural production methods such as reducing the use of chemical fertilizers and promoting the use of animal manure as natural fertilizer must be adopted. By taking such proactive steps, the world can build sustainable, more resilient food systems that can weather both the trade and climate upheavals.

Carin Smaller is Advisor on Agriculture and Investment at the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD).