World Politics Review | 20 Jan 2010

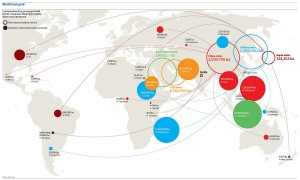

Michael Kugelman and Susan L. Levenstein In the aftermath of Copenhagen, many observers are lamenting the apparent unwillingness of governments to confront climate change. However, this unwillingness simply reflects an essential truth about public policy: The immediate always trumps the distant. For most policymakers, the threat of climate change remains a distant one. Governments prioritize immediate threats, even if doing so hastens the melting of glaciers and the rising of sea levels that may eventually destroy habitats and nations. Another vivid illustration of this mindset is the acquisition by foreign governments of vast tracts of farmland across the developing world. These land deals leave immense carbon footprints and threaten widespread environmental destruction, but are justified by both land-acquiring and land-ceding nations as a necessary response to pressing concerns about food security. This is no isolated trend. According to the United Nations, 74 million acres of farmland in the developing world were acquired in such deals over the first half of 2009 -- an amount equal to half of Europe's farmland. Food-importing nations, with memories of the skyrocketing global food costs and supply shortages of 2008 still fresh, are increasingly fearful about the volatility of world commodities markets. Given their rising populations and disappearing arable land, such countries have good reason to be afraid. As a result, some food importers, particularly in the Persian Gulf and East Asia, are now foregoing imports altogether and instead investing in foreign farmland to use for food production. They are joined by private agri-business firms, which perceive farmland as a wise investment in a food-insecure era. Meanwhile, nations whose land is targeted, many of them dependent on international food aid, are desperate for agricultural investment. Though blessed with arable land, their farm yields are flat and their agricultural sectors flagging. Heavy doses of foreign capital, they reason, will enhance farming technology, improve crop yields, and ultimately end hunger. Although these hoped-for effects are not guaranteed, many governments in these countries welcome foreign interest in their land, and actively seek out prospective investors by dangling tempting tax incentives. Pakistan has even offered a 100,000-strong security force dedicated to protecting such investments. Foreign land investors favor the large-scale industrial agriculture techniques popularized by the "Green Revolution" of the 1960s. However, these methods are anything but green. Forests are torn down to accommodate the need for large cultivation areas. To maximize high crop yields, investors use diesel-spewing tractors, pesticides, fertilizers, and other fossil-fuel-based technologies. Deep plowing and heavy water use degrade land and tax natural resources. Such environmentally destructive agriculture differs markedly from the organic forms of farming now gaining popularity in the developing world. This all portends an environmental nightmare. The prime targets of farmland investment -- Central Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America -- are home to most of the world's remaining tropical rainforests. Industrial agriculture could fell considerable areas of this forest land and release vast quantities of carbon into the atmosphere. The world's largest tropical rainforest, the Amazon, is particularly vulnerable. Land investors are increasingly turning their attention to South America, a region boasting a slew of tantalizing qualities, including nutrient-rich soil, water-laden farmland, and ample land for rain-fed crop production. In short, major portions of the world's carbon-storing ecosystems could be destroyed, leaving aggressive regimes of carbon-emitting industrial agriculture in their wake. Yet don't expect such scenarios to prompt those most responsible to modify their behavior. Investing countries, intent on satisfying immediate food needs, are driven by short-term calculations that rule out longer-term considerations about environmental sustainability. Meanwhile, host governments are unlikely to pressure land-hunters to pollute less. They have little incentive to antagonize deep-pocketed investors who promise high levels of farming capital, technology, and infrastructure. Predictably, Cambodian farmers' groups report that Phnom Penh is setting aside national regulations on forest protection and preservation so that foreign firms can convert forests into large-scale plantations. By taking such positions, investors and hosts succumb to a flawed line of zero-sum reasoning. Improving food security, they seem to suggest, means disregarding environmental concerns. Yet in reality, food security is enhanced by greener farming. For example, crop yields can be increased through organic agriculture. Additionally, environmentally destructive farming practices can endanger food security. Furthermore, investors often appropriate unoccupied land they deem fallow, and use it for industrial agricultural production -- even though some people depend on this land as a source of wild food. This can stir anger and unrest among local populations, jeopardizing the stability of farming investments and consequently the food security of investing countries. Key stakeholders in large-scale land acquisitions must acknowledge these linkages between food security and the environment, and act accordingly. At the least, investors and hosts should embrace the more small-scale model of contract farming, which affords green-minded local communities more control over how their land is used for food production. Additionally, the media and environmentalists must intensify their focus on the environmental costs of international farmland transactions. The partners to these agreements are more likely to be swayed by shaming campaigns than by international codes of conduct or other normative mechanisms, which would lack the teeth to elicit compliance -- particularly from the largely undemocratic governments involved in the deals in question. Finally, the international community must strengthen the available alternatives to safeguarding food security in environmentally friendly ways. One such alternative is a fledgling -- but promising -- initiative to establish regional food reserves that countries can draw upon when local food supplies are exhausted or threatened. If such policies are not given proper attention, then so long as the global race for farmland continues, the assault on the environment will as well -- with troubling implications for food security. Michael Kugelman and Susan L. Levenstein are, respectively, program associate and program assistant with the Asia Program at the Washington, D.C.-based Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. They are the editors of the new book Land Grab? The Race for the World's Farmland. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected].Who's involved?

Whos Involved?

Carbon land deals

Dataset on land deals for carbon plantations

07 Oct 2025 - Cape Town

Land, life and society: International conference on the road to ICARRD+20

Languages

- Amharic

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Català

- Dansk

- Deutsch

- English

- Español

- français

- Italiano

- Kurdish

- Malagasy

- Nederlands

- Português

- Suomi

- Svenska

- Türkçe

- العربي

- 日本語

Special content

Archives

Latest posts

-

KKR acquires ProTen from Aware Super

- Business Wire

- 01 July 2025