Land cleared for palm oil plantation in Darlak, Mamit District, Mizoram. Photo by Lalvohbika via Mongabay report.

India’s oil palm grand plan: at what cost?

India is currently experiencing a major transformation in its oilseed sector, marked by ambitious plans to expand the cultivation of African oil palm. Yet this grand plan casts a shadow over the nation’s diverse oilseed crops, sounding alarms bells for farmers, public health and the environment.

India has become a leading global consumer of palm oil, representing over 20 per cent of the world’s consumption. Its uses extends beyond cooking; it serves as biofuel and is used in processed foods and cosmetics. A staggering 99 per cent of this palm oil is imported, primarily from Indonesia and Malaysia.

To tackle this heavy import reliance, in August 2021, the Indian government launched the National Mission on Edible Oils - Oil Palm. The goal is to expand oil palm cultivation areas and incentivise production. As of January 2022, approximately 370,000 hectares were under oil palm cultivation. The programme seeks to cover an additional 650,000 hectares by 2025-26, with 328,000 targeted for India’s Northeast region and 322,000 for the rest of the country, hitting a target of 1 million hectares.

India’s crave for palm oil is a relatively recent phenomenon. India has historically boasted a diverse array of local oilseed varieties like castor, coconut, sunflower and sesame oil. However, over the last two decades, the oil seed sector has been severely undermined by corporatisation and trade liberalisation. This has led to the shift from self-sufficiency to import dependency, and from an economy driven by small entrepreneurs to one dominated by multinational corporations. As a result, consumption patterns in India started changing. Consumers began to accept palm oil as their main cooking oil instead of their locally available traditional oil, such as coconut oil in Southern India, mustard in North and Eastern India, or cottonseed and groundnut in Western India.

India now imports around 60 per cent of its edible oils, with palm oil accounting for approximately 65 per cent.

Massive plan for expansion of oil palm

The Indian oil palm mission selected two priority regions for palm expansion: the Northeast states and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. In 2020, a committee of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research and the Indian Institute of Oil Palm Research identified a potential area of around 2.8 million hectares, with 962,000 hectares designated for the northeastern region. This was accompanied by a government financial outlay of USD 1.32 billion, aiming to provide substantial subsidies and financial benefits to encourage farmers to venture into oil palm cultivation.

As part of this, the government committed to guaranteeing a price for oil palm produce, meant to shield farmers from global price fluctuations. These measures have a clear goal: to substantially increase crude palm oil production and significantly raise palm oil consumption. The target is ambitious - aiming for a consumption rate of 19 kilograms per person annually and a production scale of 1.12 million tonnes by 2025-26.

Northeast oil palm plantations and the adverse experiences in Mizoram

Some states in the Northeast, like Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura are not new to oil palm. In 2018-19, the total cultivation area in the Northeast was 38,358 hectares, with Mizoram leading at 26,730 hectares.

It is here where the fallout of two decades of oil palm plantations is perhaps the most stark. A 2023 report on oil palm expansion in India’s Northeast region exposes its disastrous impacts in Mizoram, notably the depletion of water due to excessive demands in oil palm plantations and the depletion of soil fertility due to heavy usage of chemical inputs.

Oil palm is incredibly water-intensive, demanding about 300 litres per plant daily, totalling around 45,000 litres of water per hectare per day. In conversations with GRAIN, A.C. Zonunmawia, Chairman of the Centre for Environment Protection in Mizoram, emphasised its dire impact on groundwater, such as depleting water resources. Despite the heavy use of chemical inputs by oil palm farmers, the exact impact on water sources remains unknown due to the lack of laboratories in the region to check pesticide contamination in water.

In addition, research on soil biology of oil palm plantations by C. Zohmingsangi, a scholar at Mizoram University’s Department of Environmental Sciences, revealed the deteriorating physicochemical properties and enzyme activities of oil palm soil in comparison to forest soil (used as a control sample). The most alarming observation was the stark absence of soil macro-organisms like ants, earthworms, centipedes, and millipedes in the study sites, underscoring the profound disruption of soil ecosystems.

Rattling community life

The shift in land use in favour of oil palm plantations in community-owned land has significantly disrupted community life. With oil palm plantations, control over land management has shifted from the hands of gram panchayats (village councils) and local community-based councils to those of oil palm companies, locking down land management under these plantations. This has dealt a severe blow to the traditional jhum practice.

Jhum, a traditional agricultural practice among Northeast tribal groups, involves rotating land for temporary cultivation. In Mizoram, the area under jhum cultivation decreased by about 20.74 per cent between 2015 and 2019. Mizoram’s own government reports have pointed the finger to oil palm cultivation as a key factor contributing to the decline in jhum areas, evident in the rapid expansion of oil palm plantations in Mizoram from a mere 1,878 hectares in 2010-11 to a staggering 26,730 hectares in 2021-22. In these areas, future jhum cultivation becomes restricted for at least 15-20 years.

This rapid decline in jhum cultivation and transition to individual farmland have led to a marked reduction in the involvement of women farmers in agriculture. Historically, women played pivotal roles in jhum cultivation, responsible for household food production, land tilling, and decision-making regarding crops. However, the practice of individual land titling, usually under male family members, has excluded women from ownership rights and crucial land-use decision-making processes. Their roles shifted from equal partners in jhum cultivation to labourers sorting and pounding fruitlets, earning little from oil palm production.

False promises

The big shift to oil palm farming in Mizoram can be attributed to the substantial support provided by the company Godrej Agrovet during the initial plantation years. The company doubled its buying rate of fresh fruit bunches to USD 0.12 per kg in 2021. On top of that, the Indian government extended support through a direct benefit transfer of USD 0.42 per kg, deposited into the farmers’ accounts. However, Vanlal Ruata Pachuau, an oil palm farmer in Mamit District, disclosed to GRAIN that while he received the government’s share in his account last year, it has yet to arrive this year. He noted that only Godrej Agrovet engages in procurement from farmers, unlike the other two designated industries in Mizoram - Ruchi Soya and 3F.

By and large, farmers have been left on their own when facing setbacks in their oil palm ventures. A study conducted in Mizoram’s Kolasib district revealed that attempts by most farmers to practice intercropping and mixed cultivation within oil palm plantations often failed. Intercrops frequently yielded poorly or were unsuitable for harvest when grown among the palm trees. This has been the case of pineapple, which, according to research scholar Lalawmpuia from the University of Mizoram, had been advised to be grown as an intercrop but failed due to inadequate sunlight under the palm canopy. Farmers on hill slopes face an additional challenge, notes Lalawmpuia. Their fruits are of inferior quality compared to those from the plains, making them less attractive to buyers. As a result, many are abandoning oil palm cultivation.

This is corroborated by Dr Vanramliana, of Pachhunga University College’s Department of Life Science. He adds that harvesting palm bunches uphill- each weighing 20kg and 30kg - requires extensive labour, making it expensive. Yet, as Mizoram hill farmers gradually pull out of oil palm cultivation, repurposing this palm land for other crops proves to be challenging.

Uncertainty over oil palm in Andaman and Nicobar Islands

In the meantime, the national oil palm mission’s intention to expand in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, has come up against a few setbacks. This is mainly due to the government ignoring a 2002 Supreme Court ban on plantations there. Already in 2018, the local administration, seeking to divert 16,000 hectares of forest land for oil palm, petitioned the Court to lift the ban. However, the Court sought guidance from the Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education (ICFRE), which recommended caution, urging detailed ecological impact studies and avoiding oil palm introduction in biodiversity-rich areas, including grasslands.

In a note submitted in January 2023 by an expert panel assisting the Supreme Court in forest and wildlife cases, the panel called attention to past oil palm plantations’ failures in the islands, cautioning against forest land diversion. They deemed such permissions in violation of the Forest Conservation Act, which, if approved could potentially set a precedent for similar agricultural activities on forest lands across more states.

The lobbying of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil

Environmental and civil society groups in the Northeast are very concerned by the push for oil palm in their region. This area holds the last remaining rainforests of the subcontinent, vital for diverse flora, fauna and various crop species; known as a hub for rice germplasm and abundant in wild relatives of crops, medicinal plants, and rare plant species.

A significant portion of these forests is traditionally managed by communities. The encroachment of oil palm plantations threatens to strip these communities of their customary forest rights. In Arunachal Pradesh, where 62 per cent of the forest cover is community-managed territory used for jhum cultivation, the misconception that jhum lands are ‘degraded’ or ‘unproductive’ is exposed. These lands are essential income sources, crucial for the food sovereignty and livelihoods of northeastern communities. The cautionary tale of Indonesia, where 41 per cent of palm plantations replaced former rainforests, should serve as a warning about the consequences of such projects.

As was expected, these oil palm developments have not escaped the radar of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), which is cunningly establishing a foothold in India’s Northeast. It aims to promote oil palm plantations, conducting consultations with farmers on sustainability, while also seeking strong partnerships with India’s palm oil industry. More importantly, however, it is trying to reduce community resistance to oil palm expansion.

Extensive evidence from Indonesia and Malaysia stresses concerns with RSPO-certified plantations. Allegations tie these plantations to human rights violations, land conflicts, displacement of indigenous communities and forest dwellers, and environmental degradation. RSPO is deemed more of a marketing tool than a credible mechanism for holding palm oil companies accountable for such violations. It has made minimal efforts to address social, labour, and environmental issues, often prioritising superficial plantation “touch ups” while maintaining an agenda of unchecked expansion.

People's resistance

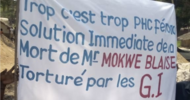

As disillusionment spreads and people see beyond the hype, opposition to oil palm plantations is rising in the Northeast region. In Manipur, a May 2022 public discussion vehemently declared that oil palm plantations must not proceed without the community’s consent. One suggestion emerging from this discussion advocates for cultivating mustard as an alternative to oil palm and producing mustard oil. Similarly, in Nagaland, the Naga Students Federation (NSF) raised serious concerns about the long-term negative impacts of oil palm plantations on health, forests, biodiversity, and the soil quality.

In Assam, progressive political parties have urged palm oil companies, notably Patanjali Foods of Baba Ramdev, to cease their oil palm cultivation initiatives. This call emphasised the substantial risk posed to the region’s environment and biodiversity. Additionally, several members of Parliament from the Northeast, spanning various political affiliations, have collectively urged the Indian government to reconsider oil palm cultivation in the region.

And like a pebble in the Indian government’s shoe, Meghalaya remains the sole dissenting state among the seven designated for oil palm expansion. Notably, both the agriculture and health ministers of Meghalaya have openly opposed the drive to promote oil palm plantations, underscoring concerns regarding social, environmental, and community livelihood impacts.

As the country pushes forward with oil palm expansion, Meghalaya’s stance speaks volumes about the serious issues at stake.