Sahara Reporters | 30 October 2023

Investigation: Franco-Luxembourg company Socfin's craze for rubber and oil palm exports linked to rights violations, pollution, and displacement of indigenous people in Nigeria

by Elfredah Kevin-Alerechi

Elfredah Kevin-Alerechi’s six-month investigation uncovers how the Okumu Oil Palm Company PLC craze for rubber and palm kernel has been linked to displacement of indigenous people, deforestation, and rights violations in Nigeria's host community. To find out how much pollution, human rights violations, and displacement Okumu Oil Palm Company PLC, a division of the Franco-Luxembourg company Socfin, was responsible for, the reporter read the Nigerian Land Act, studied the Edo Forest Ordinance, analysed the Global Forest Watch data, and glanced at the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples before travelling to the remote community.

As the reporter approached the community while still seated on the engine boat driving down the river, she noticed children swimming, washing clothes, and drinking from the Okomu river.

The river has been their sole source of domestic water. Fishers, mostly women, catch fish from the river and sell them nearby to feed and educate their children. A sparse community surrounded by bushes and surrounded by a river. Most houses were built with mud, with some cement to smooth and beautify the structure.

Socfin earns millions of naira annually from rubber and palm oil exports, but the Okomu community does not appear to be a community hosting a multinational corporation. In 2022, the company earned N59 billion, with a gross profit of N39 billion. This surpassed its 2021 gross profit of N21 billion and revenue of N37 billion. The Okumu community does not appear to be a location where Socfin makes billions of naira from the sale of its products.

Okomu community in Ovia South-West Local Government Area of Edo State is a remote community and has no road leading to the community—residents must take the river, a nine-minute motorboat ride to the coconut camp near the company site, then more than an hour across the plantation before reaching a nearby town with access roads to the city.

Oil palm fruits are used as raw materials in various products, ranging from cooking oil to cosmetics. Rubber is used to manufacture kitchen utensils, shoes, and gloves, but most notably in the manufacture of tyres. Europe consumes over a million metric tonnes of rubber per year but produces none. Socfin exports the majority of its rubber to tyre manufacturing plants on the old continent.

The community is paying the price for Socfin's need to export rubber and palm oil to Europe. As with rubber, the company exports palm oil to Europe, including directly to consumers. In Britain, you can buy this oil online on eBay for £20 for 2 litres, and on Etsy for £25.

When plantations trump humans

Edo State lost 38.7 kha of humid primary forest from 2002 to 2022, and the total area of humid primary forest in Edo decreased by 24% within this time period, according to Global Forest Watch. However, Ovia South-West, where the company operates, ranks fourth in forest loss, with 35.8 hectares lost, and Owan West lost 16.4 hectares. The reporter could not independently confirm whether the company was the primary cause of the forest loss.

For Socfin to establish its plantations, three communities—Lemon, Oweike, and Agbede—were destroyed between 2005 and 2008. As a result, hundreds of indigenous people were displaced.

Residents accuse the company of demolishing the three villages: Lemon in 2005, Oweike and Agbede in 2008, resulting in the forced displacement of indigenous people as well as the destruction of agricultural land and the inability of children to attend school. Many of those affected had no relatives outside of their village who could help them. Residents say they are still feeling the effects of the destruction of these communities several years later.

Our investigation confirms that at the time these three villages complained of being evicted, the company expanded its plantation and acquired 1,969 hectares of oil palm trees and 1,811 hectares of rubber trees. The company has since expanded and now controls 33,112 hectares, according to its website.

While the Lemon community no longer exists, residents of Oweike and Agbede have relocated across the river to settle, but they continue to live in fear of future demolition.

Austin Lemon was only 15 years old when he saw Socfin and security agents arrive in his village. He says his parents and other Lemon residents pleaded in vain with Franco-Luxembourg society to let them stay because they had nowhere to go. His father, Lemon, founded the community in 1969 and gave it his name. According to Nigerian customary law, in fact, the first person to live on virgin land for a long period becomes its owner.

He told the reporter that he spent the majority of his life in the coconut camp before his father founded the Lemon community.

Now 33 years old, Austin Lemon remembers how shocked his father was to learn that Socfin could get its hands on his ancestral home. The villagers' demands for compensation for their resettlement also went unanswered. “The company planted its palm plantation after demolishing the Lemon community,” he said. All the houses in Lemon were destroyed, as were the reserved areas where the villagers grew plantains, cassava, cocoyam, and cocoa.

“For a year I didn't go to school,” Lemon continues, “because we were displaced and had to fight for our survival.

“It was the company's action that caused the death of my father, who suffered from high blood pressure. He died because the agricultural land that provided food for his 32 children was also destroyed.

A contested land title

The Okumu Oil Palm Company denies these accusations. Representatives of the company, which we approached for this investigation, said it acquired the land for its plantation from the government after it degazetted part of the Okomu Forest Reserve in accordance with the legislation of Nigeria.

The Land Use Act of 1978 allows a state governor or local government to revoke a right of occupancy if the land is needed for public use. The law stipulates that when a right of occupation is thus revoked, the occupants and holders must be compensated for the value of the land. According to its spokesperson Ajele Sunday, the Okumu community has never been compensated, even though Socfin claims to have acquired the land from the government.

According to Nigerian lawyer Liborous Oshoma, before the government can revoke a certificate of occupancy on grounds of overriding public interest, a court must confirm that it is indeed a public interest transaction. “The public interest is, for example, that the government wants to build a road, a school or provide public services to everyone,” he explains. No taking land and giving it to a company.

However, community members with rural land predating the 1978 Land Use Act "can donate land to the government for development", it says.

According to several sources in the Okomu community including traditional rulers, the company negotiated with the government without consulting the community. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, on the other hand, enshrines the principle of "free, prior, and informed consent." This gives indigenous peoples the legal right to approve or disapprove of any project impacting their lands.

When Socfin blocked the community's only access road

Okumu villages are remote communities accessible only by passing through the company's grounds, which are densely forested with oil palm and rubber plantations. For first-time visitors, the journey can be intimidating. This is the path the reporter took with non-resident fixers to get there. After more than an hour's drive from the Udo community, it took half an hour to cross the plantation, arrive at Makilolo camp, an empty village with a few thatched houses, and board a motorboat. The reporter arrived fifteen minutes later at the Okumu community's administrative headquarters to hear testimonies from residents affected by Socfin.

It is this same road that fishermen and farmers must use to transport their products to the city market. Children also use it to get to school outside their community.

This did not prevent Socfin from having a huge ditch dug around its plantation in 2022. Residents could no longer enter or leave. During the rainy season, they say, fertilizer-laden ditch water pollutes the Okomu River, their only source of drinking water, and kills fish. There are video recordings that show the overflows of this ditch in the village of Marhiaoba, also known as the AT&P community.

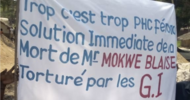

In May 2022, residents staged a peaceful protest at the entrance to the company, demanding the closure of the ditch. We obtained photos from this protest showing people holding signs asking the company to reopen the only road leading to their villages.

It was on this occasion that, according to several testimonies that we collected, Iyabo Batu, aged 56, was shot in the knee by company security agents. The first day, the residents demonstrated in their community, and then the next day, they decided to go to the entrance to the plantation. They were blocked on the way by security personnel, who wanted to end the demonstration.

“It was very difficult for my grandchildren to go to school because the white man blocked the road ,” explains Iyabo Batu, referring to the director of Socfin. According to her, because of the gap opened by the company, the children of the village were forced to stop going to school.

“Because of this blockage, we went to demonstrate,” she continues. During this peaceful protest, security guards attached to the company shot me in the knees, and I was rushed to the clinic before going to Igbuobazua General Hospital.

Batu was hospitalised for more than a month after having knee surgery. The x-ray revealed multiple fractures of the patella. She told the reporter she was disappointed that the company never paid her hospital bills or expressed regret for the gunshot wound. In fact, in response to our questions, the company denied that one of its employees shot Ms. Batu.

It was the Nigerian NGO Environmental Rights Actions (ERA) that took care of Iyabo Batu. ERA's Rita Ukwa confirmed that her association took care of Batu, including renting her an apartment in the city for a year after she was released from hospital to prepare her to return home. Her discharge receipt shows she paid N226,940, before leaving the hospital.

The company's message in response to our questions states: "We are unable to comment on the allegation that a woman was shot and injured during a protest as no official complaint has been filed by the alleged complainant, whether to our company or to the Nigerian Police Force. Please be aware, however, that none of the security guards employed by our company have ever been authorised to carry a weapon, as the government does not allow it, and therefore, we can say with certainty that none of our security guards have shot anyone.

Police officers serving the company?

However, according to several witnesses inside and outside the company who agreed to speak to us, a company security agent is indeed involved. An employee of the company not residing in Okomu identified the individual who shot Ms Batu as a government counter-terrorism agent.

Our source wished to remain anonymous for fear of the company or police officers. According to her, security at the Okumu Oil Palm Company is provided by police officers, private security guards, and the military. Although the federal government pays these agents, they are paid by the company and follow its instructions.

According to Ajele Sunday, community spokesperson, when Ms Batu was rushed to the Iguabazua division police station, officers there used delaying tactics. “At the station, the police never wanted us to take photos or film the scene,” he explains. They refused to give us a copy of the police statement, and instead on giving us a referral note to take him to the hospital, the police went with us to the hospital and spoke with the personnel on-site before allowing treatment to begin.

A conflict that does not date from yesterday

These events are only the latest episode in a long history of conflicts between Socfin and the Okomu community around the road crossing the plantation. According to Sunday, the company already closed the only gate to enter and exit the community in December 2010, because residents refused to sign a memorandum of understanding prepared by the company. Through this memorandum of understanding, the villagers were supposed to acknowledge that their land belonged to the Okomu Oil Palm Company and were only tenants. It was when residents refused to sign, Sunday said, that the company locked the door.

“But we discovered later that the same contract that we rejected had been signed,” he says. The company invited a few people and asked them to sign books to distribute to the community. A few days later, the company showed the signed memorandum of understanding, and everyone was shocked because what they signed was not a MOU. The reporter has not been able to independently confirm this allegation against the Socfin company.

At that time, the ERA legal team had already intervened in support of the community and challenged, through an official letter to the Okomu Oil Palm Company, the legal validity of its occupation of the affected land. According to the NGO's lawyers, the Makilolo camp existed before the classification of the forest reserve in 1950, its existence is mentioned in numerous official texts. Therefore, the forest declassification order that the Edo State government issued in 2000 to permit Socfin's expansion did not apply to these lands. “In the absence of a rental document and a valid certificate of occupancy, Okomu Oil Palm Company cannot validly claim legal ownership of the land, which would enable it to issue an eviction notice to Makilolo or to any other camp already recognised by the 1950 decree as a gazette" , stated this document in particular.

The company, however, reportedly chose to ignore the letter from the ERA legal team and refused to open the gate, forcing Okomu residents to cross the river to another neighbouring state to be able to travel to Benin City, the nearest major city. It was only six months later that the gate was finally opened, on the orders of the local government chairman at the time.

This same gate was reportedly closed again between 2014 and 2015, and only after the intervention of a Bayelsa State military commander was it reopened. According to Sunday, the company then lied to authorities, claiming that the community was a hotspot for insurgents. “When the military officers arrived to investigate, they saw this was a poor community and invited the community and the company to Bayelsa State for a conciliation meeting. » The commander then requested the gate be opened. “When they saw the level of poverty, the soldiers even provided us with a water bagging machine and a pump,” remembers Sunday.

Fishermen complain about pollution

The Okumu community is mainly made up of fishermen. According to the Tonwei community's chief planner, known as French Yabike, the massive quantities of fertilizers and pesticides used by the company for its plantations flow into the river and pollute it, making it more difficult to clean. catching fish.

This same river is used for drinking water. The company did drill a well, which initially helped the community, but, according to Yabike, it “has not been working for more than three years. We had to rely on river water that the company polluted with its fertilisers.

Oluwafumilayo Christopher, 80, was able to pay for the education of his six children thanks to fish caught in the Okumu River. Since the company polluted the river, “there are no more fish to catch,” she told us.

Dorcas Wuluku, another fisherwoman, sat in front of her neighbour's house with her palm on her cheek, seemingly lost in thought as she watched the reporter interview her neighbour, Christopher. She requests an interview without being approached by the reporter. “I want to talk about what we are suffering in this community,” Dorcas said.

Wuluku also accuses the company of polluting the river where she fishes and her children drink water. She recalls how, for more than a decade, the community could catch and sell fish at any time of day. "I used the river's fish to educate all of my children, and some people used it to build their houses," Wuluku explained to the reporter. If you had come during the rainy season, you would have seen the pollution with your own eyes. We have complained to the company several times, including protesting, but to no avail.

We collected a water sample from the Okomu river, close to the coconut camp and the company's plantations, for testing by the University of Port Harcourt's laboratory after hearing these complaints and viewing videos of water flowing into the community from the Socfin plantation.

The river water has high levels of dissolved solids and chlorine, indicating the presence of chemical fertilisers, as well as high levels of dissolved oxygen, which could harm fish. other forms of marine life.

The Missouri Department of Natural Resources says chlorine can enter the environment through fertilisers, livestock wastes, dust removers, industrial discharges, and inputs and is toxic to humans. fish, trees, and plants at low or high levels.

According to the Glenn Research Centre, water turbidity is caused by suspended solids such as silt, clay, and industrial waste. Research shows that "fish living in turbid waters lose weight, and this weight loss increases with nephelometric turbidity units, providing evidence that long-term exposure to turbidity is detrimental to growth productivity." Although the normal range for total dissolved solids (TDS) is between 0 and 5, our test result indicates 33.0 mg/l TDS. According to these experts, runoff from agricultural products and pesticides is a common cause of excess total dissolved solids, which can be harmful to ecosystems. Studies have shown that too much TDS in water harms fish, amphibians, and macroinvertebrates.

According to various research studies, the optimal level of dissolved oxygen (DO) is above 6.5-8 mg/l and is between 80 and 120%. However, laboratory results show that the tested river water has a DO level of 5.6 mg/l. According to the Department of Natural Resources Wales, “fish and other animals can suffocate and die if oxygen levels in the water drop quickly or are too low”.

The company has been informed of these findings. But the communication team of Socfin denies having polluted the river, claiming to respect environmental regulations in force in Nigeria. “The real reason for the disappearance of fish, apart from illegal net fishing, is the fuel oil flowing into the river from boats carrying illicit goods across our river border. Our company informed the Ministry of Environment and the Nigerian Civil Defense Corps of this situation, and they have apparently arrested a number of those involved. This fact was even published in a national newspaper,” the company claimed.

“We cannot comment on the erosion video and images you appear to have, as they were not attached to your email,” they added.

The company also clarified that it regularly tests the river water and that its last test was on May 30, 2023. We took our own river water samples on July 17, 2023.

Local leader Young Christopher attests that after drinking water from the Socfin-polluted river, residents frequently need to treat themselves with local herbs. He also urged the government and the company to act quickly to alleviate this suffering.

Community-gratifying scholarships

Several company residents said the company provides an annual scholarship of N80,000 (less than ($100) to just three Okumu students, an amount that many community leaders, including Christopher, say is insufficient.

However, the company claims to have paid one hundred and ten thousand naira to each scholarship beneficiary in Okumu community. “In 2022 alone, 38 students received N110,000.00 each and not N80,000.00. In 2023, this number increased to 46 beneficiaries. Approval letters for 2022 and 2023 are attached, as well as a copy of payment checks issued for 3 beneficiaries in 2022 ,” Okomu Oil Palm Company wrote to us.

A cry for help

Okumu residents say they have written to the government about violations of their rights and land grabbing by the company, to no avail, they say.

The letter, which the reporter cited, reveals that on September 10, 2020, the community wrote to then-President Muhammadu Buhari and the Edo State governor requesting to intervene. However, nothing appears to have been done to correct this situation.

Chris Osa Nehikhare, spokesperson for the Edo State government, denied knowledge of a letter sent to the government but said the government would look into the matter to avoid exploitation.

“I don’t know if the government received the letter because it did not reach my office,” Nehikhare told the reporter. The state government monitors what the company does to ensure that Edo residents receive fair treatment, and that is why I have copies of the names of scholarship recipients from the Edo communities, home of Okomu since 2016 until today.

“The government is always interested in how big companies interact with their host communities, and we always encourage them to make those communities their best friends.

“Government will also monitor what is happening in Okomu to ensure that no one is exploited and to improve the lives of the community,” he concluded.

This investigation was supported by JournalismFund Europe.