Mongabay | 11 August 2023

Investigation confirms most allegations against plantation operator Socfin

-

After visits to plantations in Liberia and Cameroon, the Earthworm Foundation consultancy has confirmed many allegations against Belgian tropical plantation operator Socfin.

-

Investigators found credible claims of sexual harassment, land disputes and unfair recruitment practices at both of the sites they visited.

-

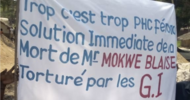

Activists in both countries remain unsatisfied, saying the consultancy should have spoken to a wider range of community members and calling for Socfin to answer directly to communities with grievances.

by Victoria Schneider

International environmental consultancy the Earthworm Foundation has released findings from field investigations it conducted in April and May this year into grievances against two plantations owned by Belgian multinational the Socfin Group.

EF investigators visited the plantations run by Socfin’s subsidiaries, one in Liberia and the other in Cameroon, where communities and local and international organizations had raised serious allegations of sexual harassment, land grabs, pollution and unfair labor practices.

EF plans further visits to other plantations, but in two reports covering the first phase, the investigators confirmed the majority of the allegations that were subject to the investigation.

At Liberia’s Salala Rubber Plantation (SRC), one of two Socfin owns in the West African country, EF’s team found that allegations of sexual harassment were credible. They found that women at SRC were fired or denied work for refusing to engage in sexual acts.

A ”Gender Committee” that the company set up in 2017 failed to pick up any of numerous cases of sexual harassment, including complaints by women about being touched inappropriately without their consent. The EF team also found that work at the plantation is generally contracted and of a short-term nature, and several affected communities had been left out of recruitment processes.

In Cameroon, the investigators visited the Dibombari oil palm plantation, one of six run by Socfin’s Cameroon subsidiary, Socapalm. They confirmed reports of rape and sexual harassment of women by employees on the plantation, including one case confirmed by a local doctor. Socapalm’s investigation of the case, however, was halted after “the alleged perpetrators and the families of the victims fled,” said the report.

EF’s team also found that an ongoing conflict over land that Socapalm’s lease stipulated would be returned to the communities has not been resolved. Further grievances around access to and the protection of sacred sites inside the plantation remain.

Investigators also found that despite the presence of company-built hand pumps, access to drinking water for resident communities was limited. However, they found no evidence that community members lacked access to health care facilities or schools.

The consultancy came up with a set of recommendations for each of Socfin’s subsidiaries. It gave Salala Rubber Corporation a time frame to respond to the problems identified with an action plan. “It is clear that although SRC is trying to address issues related to sexual harassment and resolving grievances with local communities, they still have a long way to go to fully address these in a robust manner,” the investigators wrote.

Francis Colee, head of programs at Liberia’s Green Advocates, which is supporting community members in a lawsuit against the company, said the investigation has only clouded Socfin’s involvement in socially and environmentally damaging practices.

“This is why we maintain that Socfin should directly face the affected communities instead of going through intermediaries, like EF,” Colee said. He added that even though EF found the majority of allegations to be credible, the nature of its relationship with Socfin means it’s biased and not genuinely interested in pushing for real change.

Emmanuel Elong, president of Synaparcam, a Cameroonian organization defending the rights of communities, welcomed the report’s confirmation of many of the allegations raised by his group. However, referring to concerns raised by Synaparcam and affected community members about EF’s conduct prior to the investigation in April, he said the investigators could have done more: “If Earthworm had pushed its investigation a little further by questioning people who were not selected by the traditional chiefs, the result of the investigation should be totally positive in all the points of the investigation,” he said.

One of the communities’ main criticisms has been the continuous certification of Socfin’s plantations by the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) over the years. “The report clearly shows that the Socapalm Dibombari plantation does not deserve RSPO certification. In the coming days we will produce the report of our parallel investigation which will be opposed to that of Earthworm and Socfin will be able to have a clear idea of the claims of the communities.”

EF said it will soon move ahead with the second phase of the investigation, which includes other Socfin operations in Liberia and Cameroon, as well as plantations in Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Cambodia.

In a statement responding to EF’s reports, Socfin said it was already working to address problems that have been identified, but acknowledged that it needed to do more. The company restated its earlier commitment to publish action plans and said it would work with communities and local NGOs and announce progress on a quarterly basis.