East Asia Forum | 17 July 2012

Energy, food and climate crises: are they driving an Indonesian ‘land grab’?

Author: John McCarthy, ANU

A recent Oxfam report estimated that since 2001 investors have bought, leased or licensed up to 227 million hectares of land across the globe.

This new bubble of speculative investments or ‘land grabs’ is expanding, with new market opportunities for food crops, industrial cash crops and bioenergy production, along with new carbon sequestration projects. But these figures cannot be taken at face value.

While some analysts may lump together disparate land transactions as ‘land grabs’, new research shows that only a fraction of development projects associated with these transactions are ever implemented.

The logic underlying different land acquisition processes varies from place to place. In Indonesia, for example, there are extravagant development plans. Reports indicate that state planners have allocated up to 3.5 million hectares for new food estates, with plans to allocate a further 7 million hectares to new oil palm plantations by 2020 and 9 million hectares to new timber plantations by 2016. The Ministry of Forestry also aims to expand non-gas and oil mining to encompass an additional 2.2 million hectares of ‘forest land’. These plans sit alongside ambitions to develop 1.5 million hectares of jatropha to make Indonesia the world’s first biofuel superpower. Meanwhile, donors and carbon investors compete to advance some 44 carbon sequestration, Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation initiative (REDD+), projects over millions of hectares to mitigate climate change.

But in the past many land acquisition plans have gone awry due to a host of conflicting issues including the use of existing land, resource access, ecologies and rapid fluctuations in world commodity prices. But why do developers continue to promote large-scale land acquisition in the same landscapes despite this history of failed large land schemes?

In many cases, regardless of the legal provisions, land is acquired without the intention of using it for the purposes outlined in the development license. Many are ‘virtual acquisitions’, which allow investors to appropriate subsidies, obtain bank loans using land permits as collateral, extract timber, or speculate on future increases in land values without developing the land. For instance, state agencies have granted oil palm plantation licenses over 26 million hectares of land. However, Indonesia’s 33 large oil palm corporations only manage to plant around 300,000-400,000 of new oil palm each year.

Overlapping land claims mark Indonesia’s rural landscapes, with competing indigenous and commercial smallholder land uses, or concession licenses and land use plans. Localised tenure practices can be decisive for accessing land in Indonesia’s outer islands, though lawful land acquisition processes remain critical. The interaction between localised, vernacular practices and legal processes affects the extent to which legal transactions can lead to enduring changes in the patterns of land use.

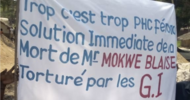

Meanwhile, land conflicts often arise when companies try to ‘free up’ the land. In 2011, the National Land Agency reported 2791 disputes, while the National Commission on Human Rights noted that 738 land disputes generated 4502 formal complaints of rights abuses. Many of these conflicts have led to violence — and sometimes even to fatalities.

The situation in Indonesia is significant for wider discussions about ‘land grabbing’ around the world. Research into land acquisition in other countries support these findings: land acquisition may not be as massive as suggested and the acquisition process is often decentralised, with local actors playing a key role. Planned projects in other countries are also often only partially realised or unlikely to succeed. As is the case in Indonesia, policies to avoid speculative uses — such as ‘virtual’ land acquisitions — tend to be poorly implemented.

Finally, these land acquisitions often adversely effect local development. Policies and schemes that demonstrate a bias toward large-scale development models involve significant capital investment without paying adequate attention to local populations. While livelihoods are becoming less tied to the land, land can still serve as a primary source of social security for the rural poor by providing a basic means of livelihood, making food more available and offering a buffer against external shocks. Even if acquisitions are ‘virtual’, there are opportunity costs: local people may neither find employment in new estates nor obtain secure access to the land concerned, especially if there is little activity in the field.

Given the severe adverse effects of climate change on agricultural productivity, more attention needs to be given to increasing the resilience of the crops and the cropping systems of poor smallholders.

Advocates for alternative policies strongly question arrangements that seek to attract large-scale investors by offering ‘free’ land or forest. The Indonesian government needs to implement policy that pursues other smallholder-friendly pathways. Given the increasing value of land, the state is arguably in a much stronger bargaining position to set the terms of investment in ways that support smallholder inclusion. Where investments do occur, the government could implement policy that safeguards against risks to smallholder welfare and checks unproductive speculation.

John McCarthy is a Senior Lecturer at the Crawford School of Public Policy, the Australian National University.

A version of this article was first published here in The Journal of Peasant Studies.