Le Monde diplomatique | August 2011

by Alain Vicky

Buganda is the largest of the traditional kingdoms in Uganda; there are 6 million Baganda (of Uganda’s 32 million people) between the shores of Lake Victoria, the capital Kampala, and the centre of the country. They “feel that Buganda land is being inexorably taken over by non-Baganda,” said historian Phares Mutibwa. “This is causing a lot of resentment. There is bad blood between the new owners of land in Buganda and the Baganda peasants. The evictors of today may become the evictees of tomorrow” (1). The Bugandan spokesman, Charles Peter Mayiga, said: “The land that belonged to us is getting more and more valuable. We want it back, so we can sell or rent it out ourselves, but the government doesn’t want to know: it acts like it’s God.”

Uganda has a third of East Africa’s arable land, and has become a magnet for foreign investors, mainly from the Gulf and the Indian subcontinent. Over the last four years, 800,000 hectares have been sold or rented out on long lease. In Kampala, where there has been frantic housing speculation, the population has risen from 2,850 in 1912 to 2 million, crammed into 201 sq km. The wars in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) at the end of the 1990s and in South Sudan up to 2005, and the electoral crisis in Kenya in 2007, led many to invest in the security of land. “There is no easier way to launder money,” said lawyer David Mpanga. “If you add together the money from corruption, from Ugandan officers who profited from the Great Lakes war or through embezzling aid money, then you get this explosion in land prices. You have to pay nearly $500,000 for half an acre (20% of a hectare) of land on the most sought after hills in the capital. It’s a vicious circle that attracts even more money.” It also arouses Bagandan bitterness towards the central state.

Before Kampala became Uganda’s capital at independence, it had been capital of the Buganda kingdom. This constitutional monarchy, founded in the 14th century, became the British colonists’ main partner from 1890 because of the centralisation of power and its ideal geographic position. The British had landed on the shores of the Indian Ocean and occupied the region, later described by Winston Churchill as the “Pearl of Africa”. An agreement between London and the Kabaka (king), signed in 1900, made Buganda a British protectorate. Britain paid the Kabaka £500, and took over 23,300 sq km of the kingdom (out of 50,763 sq km), including Kampala. A parcel of 906 sq km was reserved for the Kabaka, and the remaining community land was allocated to the traditional chiefs of Buganda’s 52 tribes. The law the British drew up, mailo, also allowed non-Baganda to settle there. “A mere signature on a piece of paper was all it took,” said Professor Mutibwa.

At independence in 1962, the 23,300 sq km were restored to the kingdom. The Kabaka, Edward Mutesa II, became the first president of the new Uganda. But in 1966 his prime minister, Milton Obote, who was from the north of the country, decided to put an end to this state within a state by suspending the federal constitution. He overthrew the Kabaka, and took over the presidency. On 24 May 1966, government troops led by Idi Amin ransacked the Kabaka’s palace on Mengo hill in Kampala, killing a hundred of his supporters. Mutesa II went into exile in London and died there in 1969. The state confiscated the royal land and abolished the traditional kingdoms. Twenty years of dictatorship, foreign intervention and rebellion followed, displacing many and forcing non-Baganda to settle in former royal lands. Many then sublet the land to other displaced Ugandans.

The Museveni era

Yoweri Museveni took power in 1986 after five years in the resistance movement; he owed his success to Buganda, as without its support, National Resistance Army rebels could not have taken their bush war all the way to Kampala, allowing their political wing, the National Resistance Movement, to seize power (2). In 1993 Museveni restored the kingdoms. The new Bugandan Kabaka, Ronald Muwenda Mutebi II, was crowned, and given back his palace and the 906 sq km reserved for the Kabaka’s use. But the 23,300 sq km remained in the hands of the state. Their return became an important issue in relations between the kingdom and the state.

Since the end of the 1980s, international investors have insisted that a private property market, responding to the laws of supply and demand, replace traditional land tenure. Keen to show good governance, Museveni began an accelerated programme of land privatisation. In 1998 a new law formalised tenure and made it easier to buy and sell land. District Land Boards, the new instruments of power, began putting land up for auction. As with many other reforms supported by international financial institutions, the 1998 law mainly benefited powerful private investors. The victims were occupants who had no title deeds, even though they might have lived on the land for generations. For them, land reform became a land grab.

“Legalism ... has helped no one — except perhaps those who do want to accumulate large land holdings for commercial enterprise,” wrote Anne Perkins, in The Guardian, in a blog about life in Katine village in northern Uganda. “Security of tenure offers the motive to invest and an asset against which to borrow. That — and the enthusiasm of the World Bank — was the motive behind Museveni’s bold and much debated attempt at wholesale reform, the Land Act of 1998” (3). In 2010, in a move to appease tensions, a new law allowed victims to complain to the courts. “While the government appeared to have good intentions,” said Livingstone Sewanyana, executive director of the Ugandan Foundation for Human Rights, “this attempt to put a semblance of legality on the already complex web of traditional relations between landowners and occupants only worsened the conflict over land” (4).

The Buganda kingdom used the revenue from ads on its commercial radio station, and from taxes raised on the land it still owned, to contest the law through the Buganda Land Board. The government defended itself: “Prominent Baganda figures are the main landowners in the central region, and the Kabaka is the biggest of them all. Agrarian reform will smash their system of ownership” (5).

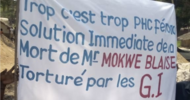

Land disputes are piling up in the courts of Kampala. The poorest small farmers can’t afford a lawyer. There have been many cases of false deeds obtained through bribery. People try to prevent land being sold without the owner’s knowledge by posting warnings on the walls of Kampala’s working class districts in the swampy land around Lake Victoria: they say “This house is not for sale”.

Eyes on the slums

Now the developers have their eyes on the 21% of Kampala that is a slum. Plots reserved for the middle classes are encroaching on these miserable informal areas, home to Acholi migrants from the north, most of whom are employed by private security companies. Prominent Baganda figures are also involved. The Kabaka’s government, on a hill opposite the Royal Palace, is split between conservatives, still demanding the restitution of the pre-1966 23,300 sq km, and young reformers, ready to compromise with the business circle around Museveni. The fate of the 906 sq km still being managed by the Buganda Land Board is angrily debated.

The 1995 constitution stipulates that the traditional kings of Uganda be confined to a cultural role. Apolo R Nsibambi, a former prime minister, said: “Article 246 forbids traditional or cultural chiefs from getting involved in politics. Why? Because when they did take part in political life, they were not content with causing division within their own kingdoms, but they also caused problems for the central government.” Buganda crossed this line for the first time in 2007 when it mobilised several thousand people to demonstrate in Kampala against the government’s decision to give 7,100 hectares of the 30,000-hectare Mabira forest, a traditional sanctuary, to the Indian company Mehta to grow sugarcane for biofuel. The Kabaka suggested leasing part of his 906 sq km of land instead. But the government refused. Three people were killed in clashes in Kampala, including an Indian beaten up by demonstrators. The authorities put the plan on hold, but from then on there was conflict between Buganda and Museveni’s government.

There was another protest in Kampala on 10 September 2009 over the government’s decision to ban the Kabaka, “for security reasons”, from visiting his subjects in a district where the traditional chief, a non-Baganda, had been appointed by Museveni. “These were divide and rule tactics, with which the head of state is very familiar,” said Yassin Olum, professor of political science at Makerere University. Around 30 people were killed in the police crackdown.

The violence could spread to other areas, since the Baganda are not the only ethnic group affected by the land grab: 80% of Ugandan land is governed by traditional tenure systems. In the north, where the Ugandan army cleared Acholi community land of all traces of the Lord’s Resistance Army (6), they don’t know where to house the two million displaced. “The war in the north of Uganda was an opportunity for people to steal land from those who were forced into refugee camps,” said Sewanyana. The emergence of a new country, South Sudan, on the other side of the border, has made this area, which used to be inaccessible, desirable (7). Usaid is building a tarmac road, nearly 600km long, between Kampala and Juba in South Sudan, as an economic corridor.

Oil and gas to exploit

But tension is highest in the west, on Bunyoro traditional land on the shores of Lake Albert, which forms a natural border with the DRC. Oil and gas were discovered there in 2006, in an area stretching north of the immense Rift Valley, and it might have the equivalent of 2bn barrels of oil. The British company Tullow Oil has a license to explore 150 sq km next to the Murchison Falls National Park. The French company Total and the Chinese National Offshore Oil Corporation have each acquired for $1.5bn a third of the shares in the Tullow oilfield. The Italian company Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi has joined the queue. Drilling is due to begin by the end of 2012 and there are plans to build a refinery that could guarantee the country energy independence (20,000-25,000 barrels a day) by 2016. The remainder would be exported to Mombasa, Kenya, via an oil pipeline partly funded by Gaddafi’s Libya: since the conflict in Libya its construction has been put on hold.

Sixty square kilometres of community land belonging to the Bunyoro were bought in 2010 (8), despite claims that certificates of ownership were obtained by bribing the Uganda Land Commission. The new owners include a Bunyoro princess, Kabakumba Masiko, who is the former leader of the National Resistance Movement parliamentary group and the outgoing minister of information; she promised: “Oil will transform the region. For the better.” The area is now protected by an elite unit of the presidential guard, led by Muhoozi Kainerugaba, Museveni’s son.

“There are not many places in the world where you can prospect for oil among lions, elephants, buffaloes and giraffes,” wrote Brian Glover, managing director of the Ugandan subsidiary of Tullow Oil, in his 2009 report. He thanked a “kingdom of Bandura Petar” for contributing to the discovery, but no one in Bunyoro has ever heard of a sovereign with that name. In Masindi, the “prime minister” (9), engineer Yabezi Kiiza, said this was “another lie. We were very happy when oil was discovered. We thought Bunyoro would be lifted out of the poverty and backwardness the British left us in. We still don’t have a university and our hospital lacks doctors. Then we discovered that everything was signed without our community having any say” (10). “When the oil starts flowing,” warned Henry Ford Mirima, spokesman for the Bunyoro kingdom, “it’s possible that Bunyoro youths will attack the pipelines.” Kiiza agreed: “We never thought we would end up having the same problems here as the people in the Niger Delta (11). But now I’m worried. More and more people are coming to eat at our table, while we are not invited. We may end up salivating so much we spoil their meal.”

Beti Olive Namisango Kamya, an unsuccessful Bugandan candidate in the 2011 presidential election, thinks she knows how to stop the ticking of the land ownership time bomb: “Uganda should become a federal state again, where each region can profit from its mineral or agricultural resources instead of them being given to the regional governments appointed by Museveni.” Federalism and the restitution of the 23,300 sq km are long-standing demands of the Buganda kingdom, grouped under the Baganda concept of afye, “our things”. Kamya notes that other kingdoms are also looking for “an alternative to the political system we inherited from the British, and which has been allowed to continue because it serves the interests of an elite.” Her party is named the Uganda Federal Alliance. Its logo is a giraffe (“an animal that sees far”) and its slogan is a quote from Victor Hugo: “Nothing is more powerful than an idea whose time has come.”

On 18 February 2011 Museveni was re-elected as head of state for a fourth five-year term. Since then, there have been protests against the high cost of living, and in support of the opposition. The political columnist Ibrahim Asuman Bisiika said: “we have not yet reached a critical mass of discontent. The Museveni generation, born in the second half of the 1980s just after he took power, are not interested in past tragedies. But the land ownership question could provoke their anger, which could spread across the country.”

by Alain Vicky

Buganda is the largest of the traditional kingdoms in Uganda; there are 6 million Baganda (of Uganda’s 32 million people) between the shores of Lake Victoria, the capital Kampala, and the centre of the country. They “feel that Buganda land is being inexorably taken over by non-Baganda,” said historian Phares Mutibwa. “This is causing a lot of resentment. There is bad blood between the new owners of land in Buganda and the Baganda peasants. The evictors of today may become the evictees of tomorrow” (1). The Bugandan spokesman, Charles Peter Mayiga, said: “The land that belonged to us is getting more and more valuable. We want it back, so we can sell or rent it out ourselves, but the government doesn’t want to know: it acts like it’s God.”

Uganda has a third of East Africa’s arable land, and has become a magnet for foreign investors, mainly from the Gulf and the Indian subcontinent. Over the last four years, 800,000 hectares have been sold or rented out on long lease. In Kampala, where there has been frantic housing speculation, the population has risen from 2,850 in 1912 to 2 million, crammed into 201 sq km. The wars in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) at the end of the 1990s and in South Sudan up to 2005, and the electoral crisis in Kenya in 2007, led many to invest in the security of land. “There is no easier way to launder money,” said lawyer David Mpanga. “If you add together the money from corruption, from Ugandan officers who profited from the Great Lakes war or through embezzling aid money, then you get this explosion in land prices. You have to pay nearly $500,000 for half an acre (20% of a hectare) of land on the most sought after hills in the capital. It’s a vicious circle that attracts even more money.” It also arouses Bagandan bitterness towards the central state.

Before Kampala became Uganda’s capital at independence, it had been capital of the Buganda kingdom. This constitutional monarchy, founded in the 14th century, became the British colonists’ main partner from 1890 because of the centralisation of power and its ideal geographic position. The British had landed on the shores of the Indian Ocean and occupied the region, later described by Winston Churchill as the “Pearl of Africa”. An agreement between London and the Kabaka (king), signed in 1900, made Buganda a British protectorate. Britain paid the Kabaka £500, and took over 23,300 sq km of the kingdom (out of 50,763 sq km), including Kampala. A parcel of 906 sq km was reserved for the Kabaka, and the remaining community land was allocated to the traditional chiefs of Buganda’s 52 tribes. The law the British drew up, mailo, also allowed non-Baganda to settle there. “A mere signature on a piece of paper was all it took,” said Professor Mutibwa.

At independence in 1962, the 23,300 sq km were restored to the kingdom. The Kabaka, Edward Mutesa II, became the first president of the new Uganda. But in 1966 his prime minister, Milton Obote, who was from the north of the country, decided to put an end to this state within a state by suspending the federal constitution. He overthrew the Kabaka, and took over the presidency. On 24 May 1966, government troops led by Idi Amin ransacked the Kabaka’s palace on Mengo hill in Kampala, killing a hundred of his supporters. Mutesa II went into exile in London and died there in 1969. The state confiscated the royal land and abolished the traditional kingdoms. Twenty years of dictatorship, foreign intervention and rebellion followed, displacing many and forcing non-Baganda to settle in former royal lands. Many then sublet the land to other displaced Ugandans.

The Museveni era

Yoweri Museveni took power in 1986 after five years in the resistance movement; he owed his success to Buganda, as without its support, National Resistance Army rebels could not have taken their bush war all the way to Kampala, allowing their political wing, the National Resistance Movement, to seize power (2). In 1993 Museveni restored the kingdoms. The new Bugandan Kabaka, Ronald Muwenda Mutebi II, was crowned, and given back his palace and the 906 sq km reserved for the Kabaka’s use. But the 23,300 sq km remained in the hands of the state. Their return became an important issue in relations between the kingdom and the state.

Since the end of the 1980s, international investors have insisted that a private property market, responding to the laws of supply and demand, replace traditional land tenure. Keen to show good governance, Museveni began an accelerated programme of land privatisation. In 1998 a new law formalised tenure and made it easier to buy and sell land. District Land Boards, the new instruments of power, began putting land up for auction. As with many other reforms supported by international financial institutions, the 1998 law mainly benefited powerful private investors. The victims were occupants who had no title deeds, even though they might have lived on the land for generations. For them, land reform became a land grab.

“Legalism ... has helped no one — except perhaps those who do want to accumulate large land holdings for commercial enterprise,” wrote Anne Perkins, in The Guardian, in a blog about life in Katine village in northern Uganda. “Security of tenure offers the motive to invest and an asset against which to borrow. That — and the enthusiasm of the World Bank — was the motive behind Museveni’s bold and much debated attempt at wholesale reform, the Land Act of 1998” (3). In 2010, in a move to appease tensions, a new law allowed victims to complain to the courts. “While the government appeared to have good intentions,” said Livingstone Sewanyana, executive director of the Ugandan Foundation for Human Rights, “this attempt to put a semblance of legality on the already complex web of traditional relations between landowners and occupants only worsened the conflict over land” (4).

The Buganda kingdom used the revenue from ads on its commercial radio station, and from taxes raised on the land it still owned, to contest the law through the Buganda Land Board. The government defended itself: “Prominent Baganda figures are the main landowners in the central region, and the Kabaka is the biggest of them all. Agrarian reform will smash their system of ownership” (5).

Land disputes are piling up in the courts of Kampala. The poorest small farmers can’t afford a lawyer. There have been many cases of false deeds obtained through bribery. People try to prevent land being sold without the owner’s knowledge by posting warnings on the walls of Kampala’s working class districts in the swampy land around Lake Victoria: they say “This house is not for sale”.

Eyes on the slums

Now the developers have their eyes on the 21% of Kampala that is a slum. Plots reserved for the middle classes are encroaching on these miserable informal areas, home to Acholi migrants from the north, most of whom are employed by private security companies. Prominent Baganda figures are also involved. The Kabaka’s government, on a hill opposite the Royal Palace, is split between conservatives, still demanding the restitution of the pre-1966 23,300 sq km, and young reformers, ready to compromise with the business circle around Museveni. The fate of the 906 sq km still being managed by the Buganda Land Board is angrily debated.

The 1995 constitution stipulates that the traditional kings of Uganda be confined to a cultural role. Apolo R Nsibambi, a former prime minister, said: “Article 246 forbids traditional or cultural chiefs from getting involved in politics. Why? Because when they did take part in political life, they were not content with causing division within their own kingdoms, but they also caused problems for the central government.” Buganda crossed this line for the first time in 2007 when it mobilised several thousand people to demonstrate in Kampala against the government’s decision to give 7,100 hectares of the 30,000-hectare Mabira forest, a traditional sanctuary, to the Indian company Mehta to grow sugarcane for biofuel. The Kabaka suggested leasing part of his 906 sq km of land instead. But the government refused. Three people were killed in clashes in Kampala, including an Indian beaten up by demonstrators. The authorities put the plan on hold, but from then on there was conflict between Buganda and Museveni’s government.

There was another protest in Kampala on 10 September 2009 over the government’s decision to ban the Kabaka, “for security reasons”, from visiting his subjects in a district where the traditional chief, a non-Baganda, had been appointed by Museveni. “These were divide and rule tactics, with which the head of state is very familiar,” said Yassin Olum, professor of political science at Makerere University. Around 30 people were killed in the police crackdown.

The violence could spread to other areas, since the Baganda are not the only ethnic group affected by the land grab: 80% of Ugandan land is governed by traditional tenure systems. In the north, where the Ugandan army cleared Acholi community land of all traces of the Lord’s Resistance Army (6), they don’t know where to house the two million displaced. “The war in the north of Uganda was an opportunity for people to steal land from those who were forced into refugee camps,” said Sewanyana. The emergence of a new country, South Sudan, on the other side of the border, has made this area, which used to be inaccessible, desirable (7). Usaid is building a tarmac road, nearly 600km long, between Kampala and Juba in South Sudan, as an economic corridor.

Oil and gas to exploit

But tension is highest in the west, on Bunyoro traditional land on the shores of Lake Albert, which forms a natural border with the DRC. Oil and gas were discovered there in 2006, in an area stretching north of the immense Rift Valley, and it might have the equivalent of 2bn barrels of oil. The British company Tullow Oil has a license to explore 150 sq km next to the Murchison Falls National Park. The French company Total and the Chinese National Offshore Oil Corporation have each acquired for $1.5bn a third of the shares in the Tullow oilfield. The Italian company Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi has joined the queue. Drilling is due to begin by the end of 2012 and there are plans to build a refinery that could guarantee the country energy independence (20,000-25,000 barrels a day) by 2016. The remainder would be exported to Mombasa, Kenya, via an oil pipeline partly funded by Gaddafi’s Libya: since the conflict in Libya its construction has been put on hold.

Sixty square kilometres of community land belonging to the Bunyoro were bought in 2010 (8), despite claims that certificates of ownership were obtained by bribing the Uganda Land Commission. The new owners include a Bunyoro princess, Kabakumba Masiko, who is the former leader of the National Resistance Movement parliamentary group and the outgoing minister of information; she promised: “Oil will transform the region. For the better.” The area is now protected by an elite unit of the presidential guard, led by Muhoozi Kainerugaba, Museveni’s son.

“There are not many places in the world where you can prospect for oil among lions, elephants, buffaloes and giraffes,” wrote Brian Glover, managing director of the Ugandan subsidiary of Tullow Oil, in his 2009 report. He thanked a “kingdom of Bandura Petar” for contributing to the discovery, but no one in Bunyoro has ever heard of a sovereign with that name. In Masindi, the “prime minister” (9), engineer Yabezi Kiiza, said this was “another lie. We were very happy when oil was discovered. We thought Bunyoro would be lifted out of the poverty and backwardness the British left us in. We still don’t have a university and our hospital lacks doctors. Then we discovered that everything was signed without our community having any say” (10). “When the oil starts flowing,” warned Henry Ford Mirima, spokesman for the Bunyoro kingdom, “it’s possible that Bunyoro youths will attack the pipelines.” Kiiza agreed: “We never thought we would end up having the same problems here as the people in the Niger Delta (11). But now I’m worried. More and more people are coming to eat at our table, while we are not invited. We may end up salivating so much we spoil their meal.”

Beti Olive Namisango Kamya, an unsuccessful Bugandan candidate in the 2011 presidential election, thinks she knows how to stop the ticking of the land ownership time bomb: “Uganda should become a federal state again, where each region can profit from its mineral or agricultural resources instead of them being given to the regional governments appointed by Museveni.” Federalism and the restitution of the 23,300 sq km are long-standing demands of the Buganda kingdom, grouped under the Baganda concept of afye, “our things”. Kamya notes that other kingdoms are also looking for “an alternative to the political system we inherited from the British, and which has been allowed to continue because it serves the interests of an elite.” Her party is named the Uganda Federal Alliance. Its logo is a giraffe (“an animal that sees far”) and its slogan is a quote from Victor Hugo: “Nothing is more powerful than an idea whose time has come.”

On 18 February 2011 Museveni was re-elected as head of state for a fourth five-year term. Since then, there have been protests against the high cost of living, and in support of the opposition. The political columnist Ibrahim Asuman Bisiika said: “we have not yet reached a critical mass of discontent. The Museveni generation, born in the second half of the 1980s just after he took power, are not interested in past tragedies. But the land ownership question could provoke their anger, which could spread across the country.”

.png?1314650769)