Fortune | 10 March 2011

By Brian Dumaine

You can't reach Melimoyu, a fishing village of 50 nestled on the rugged southern coast of Patagonia, by car. From Coyhaique, Chile, a twin-prop Piper Comanche carries me between jagged mountain peaks, through thick gray clouds, driving rain, and 50-mph winds toward a small private airstrip. As the plane banks sharply to land, the wind buffets the craft so severely that the instrument panel issues stomach-churning blips and beeps. As I cling to my seat, I take some solace in the fact that Hugo, our pilot, is wearing an olive green flight jacket with an insignia on the sleeve that looks like he was once an F-16 fighter pilot in the Chilean air force.

After a safe landing and a hearty pat on Hugo's back, I hop onto the tarmac thinking my journey is over. But no one -- and not a single building -- is in sight. Eventually a pickup truck appears and takes me to a makeshift metal dock. From there a 30-foot twin outboard carries me across a bay surrounded by rain forests, magnificent waterfalls, and glaciers -- think Avatar without the blue people. Heavy seas slam the hull as loudly as a Fourth of July cherry bomb. As we near our destination, I notice there's no dock. I jump off the boat onto a launch, which carries me to a beach where a tractor waits in water halfway up its wheels. The wooden platform attached to its rear acts as a dock. Welcome to Patagonia on a not atypical summer day.

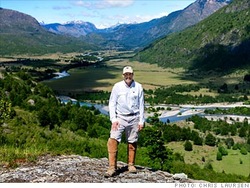

In a white two-story house near the beach waits Warren Adams, a 44-year-old American entrepreneur and the co-founder and CEO of Patagonia Sur. With his small, four-year-old for-profit company, Adams is conducting an experiment that could radically change the way land is developed, using a formula that applies the forces of the free market to generate jobs and wealth and at the same time preserve millions of acres for future generations.

As I warm by a fire in the living room of the Patagonia Sur eco-lodge, Adams, a lean, athletic man whose green eyes relay a quiet intensity, explains that Melimoyu (pronounced melly-moy-you) is only one of six holdings that Patagonia Sur (sur means "south" in Spanish) owns in the region. In all, the company has bought some 60,000 acres -- about half the size of New York City -- in some of the most remote and beautiful areas of Chile (see map). On this land the company plans to engineer as many as 10 profitable, environmentally sustainable businesses. The goal: to create proof that land can be developed for profit and remain unharmed, a vastly different theory from previous schools of land management. "It's a model," says Adams, "we hope to scale in developing nations around the world."

He may sound like a wide-eyed visionary jousting at green windmills, but Adams is backed by an impressive roster of 40 hard-nosed investors who have put up a total of $20 million so far. (The company hopes to raise as much as $200 million.) They include Howard Stevenson, a professor of entrepreneurship at the Harvard Business School, and John Fisher, founding partner of the Silicon Valley VC firm Draper Fisher Jurvetson.

So far Adams has created three income streams -- an ecotourism venture that works on a vacation club/membership-fee model, a land brokerage, and a carbon-offset business that sells credits to schools and corporations. In the future Adams plans to sell land for vacation home and eco-lodge developments and consult with local salmon farms on how to fish more sustainably. Perhaps one of his most original ideas is to float millions of gallons of pure water in giant baggies from his glaciers to drought-stricken areas of the world, but more on that later.

Adams has no illusions about the difficulty of his task. When asked what keeps him up at night, he says he worries about achieving a balance between development and conservation. At what point does sustainable development become exploitative? How many ecotourists and vacation homes are too many? What effect will taking millions of gallons of water from his land to sell overseas have on the ecosystem? Adams is creating the first private land trust in Patagonia to permanently protect the company's land. Will it hold up in the courts if challenged? Will powerful mining and agricultural interests in Chile start eyeing its gold and timber wealth as Patagonia becomes more open to the outside world?

But if his project works as planned, Adams says Patagonia Sur's investors could make around 9% annually from ecotourism and from selling limited amounts of land for outsiders to develop. The other businesses, such as water and carbon credits, he says, could eventually double that return.

Three years after its launch, Patagonia Sur is still a small operation, with estimated 2011 revenues of $4 million -- the money coming in equal shares from real estate, carbon offsets, and the $40,000 fees that Patagonia Sur's members must pay for the right to use the eco-lodges. Adams, however, says this year the business will become cash flow positive, and he invited Fortune in for an exclusive look at how his new, risky business model works.

From Amazon to Patagonia

This is hardly Adams' first go-round with a bold entrepreneurial idea. In 1996, after graduating from Harvard Business School, he gave up a safe and lucrative career as a consultant to start PlanetAll, an early social-networking company that connected college students with each other online. Adams, who grew up in Montclair, N.J., conceived the idea in 1986 when he was president of his fraternity at Colgate. With the growth of the Internet in the mid-1990s, he saw the chance to turn the idea into a real business.

In 1998 he sold the company to Amazon (AMZN) for $100 million, becoming director of product development at the online giant. For whatever reason, Jeff Bezos decided not to pursue social networking but adapted some of PlanetAll's features into Amazon -- like the one that tells you that others who attend, say, the Harvard Business School are also reading Inside of a Dog. After a couple of years there, Adams felt that Amazon, which had grown to 3,000 employees, had become too big for him. He left the company in 2000, right before the dotcom bubble burst. To this day Amazon holds a U.S. patent on social networking based on PlanetAll. (Catch that, Mark Zuckerberg?)

With his wife, Megan, another Harvard MBA (they met when PlanetAll leased space in the building where she worked), Adams traveled the world for a year. After biking through Vietnam and trekking through India, the Galapagos, and Antarctica, the couple ended up in Patagonia and fell in love with the place. "Every time someone asked us which was our favorite, we always said, 'Patagonia,'" recalls Megan.

You can understand why. This section of the Andes region, with scores of lakes, rivers, waterfalls, and rich ocean bays is home to blue whales and cougars and has not a single poisonous snake. Chilean Patagonia is about 1,000 miles long and averages only 110 miles wide (the Argentinian side is bigger). As recently as the early 20th century the Chilean region's entire population was 167. Today, the population is only 104,000, making it one of the most sparsely settled regions in the world. Picture the beauties of Jackson Hole without any of the development.

After his globetrotting was over, Adams settled on Martha's Vineyard. But the image of all that pristine land in Patagonia was hard to shake. "This land in Patagonia kept bubbling up," he recalls. "And I thought, 'Is it just a hobby, or is there real business opportunity here?'" One of the things that stuck Adams was how cheap this beautiful land was -- about $200 an acre. He was tempted to buy some himself but then had a revelation: If he just bought a half-million-dollar piece of land himself, it would be a nice piece of land, but if he pooled 40 investors who each put in a half million, "you'd have a $20 million fund and you could create a real business," he says.

What separates Adams from other conservationists is his application of free-market principles to make the land pay for itself -- and then some. Philanthropists who set aside land have often put it to limited economic use. Ted Turner, who according to The Land Report is the largest land owner in America, with 2 million acres and who owns another 100,000 acres in Patagonia (see sidebar), uses some of his land for raising buffalo to supply his chain of Ted's Montana Grill restaurants. Douglas Tompkins, the founder of clothing brands the North Face and Esprit, and his wife, Kris, have created foundations that own some 2 million acres in Patagonia, creating important and impressive sanctuaries where some recreation is allowed. But Adams' model goes well beyond that in its attempt to build multiple income streams from the land while at the same time keeping it from harm.

Adams' model is important, because there aren't enough do-gooder billionaires to save the biosphere. Tompkins, who has been buying and protecting land in Chile since 1990, thinks the well-heeled could buy and preserve enough land to make a difference, but they're just not that interested. "The thing is that the wealthy in general want to accumulate more and more money," he says. "Any simple analysis of land conservation philanthropy reveals this unfortunate fact."

That leaves it to the profit motive. "If we're going to be successful at scale," says Glenn Prickett, the chief external affairs officer at the Nature Conservancy, the Washington, D.C., nonprofit, "we have to show that these land projects are more than walled-off museums. We're only going to win the battle if these projects can pay their own way and provide economic benefit to the local communities."

Winning the battle won't be easy. Since the onset of the Industrial Age, the earth has lost half its forest cover. And of course the chainsaws keep roaring. Every year huge tracts of rain forest disappear. The tropics -- especially Brazil and Indonesia -- are particularly hard hit as growing economies in China and India boost demand for everything from beef to palm oil to sugar cane. Losing forests has a cost: Deforestation accounts for about 15% of greenhouse-gas emissions worldwide. Forests also help reduce flooding, act as a filter that cleans water, and preserve biodiversity.

Other entrepreneurs before Adams have tried this sort of land-conservation approach -- albeit on a less ambitious scale -- with limited success. Many well-meaning land investors tried limited "eco" residential land development or ranching only to find the costs higher or demand less vibrant than hoped. When Roger Lang, a Silicon Valley software entrepreneur, bought the 26,000-acre Sun Ranch in Madison Valley, Mont., in 1998, he put conservation easements on the land -- and hoped to help pay for it by building a limited number of vacation homes and doing some ecotourism and carbon storage. But the financial meltdown made it hard to sell vacation homes, and Lang sold the ranch last year.

What's different here and now? Adams believes the markets are starting to assign new values to land. In the past five years or so, Wall Street has started talking about a water market, and the U.S. carbon market, while small, is starting to grow. Some 678 American universities have pledged to go carbon neutral, which will mean most will have to buy carbon credits. Also, timber companies have begun to focus more on sustainable forestry projects. "You look around here and see 2.5 million acres that have over the last century been burned down and that could be reforested," Adams says. At Valle California the company has already planted 200,000 new trees and plans to have a million planted by the end of 2012. Every three trees planted will absorb a ton of carbon over their lifetime. Patagonia Sur sells the carbon credits for $15 a ton. So far Patagonia Sur has sold carbon credits to reunion classes at Colgate and the Harvard Business School. Watchmaker Audemars Piguet is buying credits and has taken out a $100,000 annual corporate membership to entertain clients and reward top salespeople with a trip to Patagonia.

But this nascent business has its challenges. In the U.S. the carbon markets are voluntary, making it hard to sell credits. Carl Palmer, the co-founder and a principal at Beartooth Capital, a private equity fund that invests in ranchland in the West and improves it, says, "The policy is not in place yet to have a carbon market that works well."

Adams believed it would be easier to overcome many of these problems if the company had Chilean roots. So he founded it with an American, Steve Reifenberg, and two Chileans: Franco Valdes and Felipe Valdes. Some 30% of his investors are Chilean; so are most of its 22 employees. Adams now lives in Santiago half the year with Megan and their three young daughters.

From there he can keep a closer eye on his project, which he hopes will generate $150 million in profits over the next 15 years. Patagonia Sur's lodge at Valle California sits on a 10,000-acre parcel and is an airy modernist structure that overlooks a trout stream. Membership in all the Patagonia properties is limited to 100; 50 have signed up so far. (Twelve corporate and 12 university memberships will also be offered.) The inheritable $40,000 family memberships entitle members and their guests to stay in any of Patagonia Sur's lodges for $300 a night per person. Their footprint is minimal -- the Valle California property has six yurts, luxurious domed tents that surround the lodge -- but they spare no expense: Each has a private bath and 600-thread-count sheets. The daily tariff includes food and wine, as well as activities such as horseback riding, white-water rafting, and fly-fishing. After 100 memberships are sold, anyone new wanting to join will have to buy from an existing member -- presumably at a premium to the original $40,000 investment. Adams also has a master plan for 15 vacation houses or eco-lodges starting at $350,000 but plans to develop no more than 5% of this 10,000-acre site.

Water water everywhere

The lodge and vacation homes should be attractive to the well-heeled, but will they come? The setting is stunning, the skilled staff friendly, and the food delicious, but Patagonia is far away, especially for a membership model. Harvard's Stevenson wonders whether members will use the facilities enough. "How many will travel that far more than once?" He may have a point. The destination-club industry -- whose most famous example is Steve Case's Exclusive Resorts -- has seen sales slow and many companies go out of business, and they give members access to properties around the world.

But they didn't have Adams' other ambitions. In addition to the lodges, the real estate, and the carbon-offset businesses, Adams hopes to sell water to drought-ravaged regions of the world. Patagonia is one of the wettest regions on the planet, while some 2.4 billion people live in water-stressed countries in the developing world. One idea is to store clean, fresh water in huge baggies that hold millions of gallons and float them on the prevailing current from South America to Africa. There the water will be distributed and sold. (Fresh water is less dense than salt water, so the bags float.)

Adams is not the first to try this. In 2001 a Norwegian company, Nordic Water Supply, used 5-million-gallon bags to transport water from Turkey to Cyprus but subsequently went broke. One of the bags floated away while in transit, inspiring the headline WATER LOST AT SEA.

Shipping water in bags is much cheaper than by tanker, but challenges loom large. Will the giant baggies puncture? Will they hold up in a storm? Also, how do you extract fresh water from a sensitive area like Patagonia without affecting the salinity of the bays, which in turn could harm the krill, the main food supply for the blue whales? Adams hopes to partner with Portland's Gulf of Maine Research Institute to open a marine research center in Melimoyu, which will study the blue whales that return to these waters annually.

The lodge at Patagonia Sur's eco-resort in Valle California

The institute also hopes to study the effect of salmon farms on Chile's ecosystems. Farmed salmon is one of Chile's largest export businesses, but poor aquaculture practices contributed a few years back to a disease called infectious salmon anemia that killed huge numbers of salmon and drove the industry into crisis. Patagonia Sur has reached out to the salmon farmers operating in the waters of Melimoyu, hoping to persuade them to adopt more sustainable practices. In one scenario, Adams foresees a joint venture with the salmon farmers where Patagonia Sur shares its research on sustainable fish farming to help them market healthier fish -- in the process creating local jobs.

When the small plane that's taking me out of Patagonia reaches altitude, I gaze down at a string of lakes reflecting the jagged profiles of glacier-topped mountains. It is hard to believe that this remote land will ever be threatened by development, but history teaches us not to be complacent. Adams, understanding this, hopes to spread his free-market philosophy widely. "The concept," he says, "is, Take this model and invest where land is cheap, where you have political stability and the sum of the various business units provide a healthy risk-adjusted return. We think this could work in many beautiful places in the world."

As the plane banks toward Santiago, I keep staring at the retreating mountains, wondering if he's right.