Slow Food | 21 October 2010

At one of the pivotal debates entitled “Who’s Stealing Africa’s Land?” held today at the 2010 Salone del Gusto on the topical issue of land grabbing in Africa, Carlo Petrini, Slow Food’s president said he wanted to address the white people in the audience, and present them with a paradox. “If you want to help African farmers, then help Italian farmers, or the farmers of your own country,” he said, denouncing land grabbing as “colonialist, imperial and criminal” and guided by a “perverse logic.” “We should be supporting our own farmers and letting Africans cultivate their own land in their own way.”

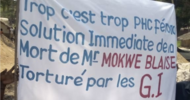

Throughout the debate experts looked at the phenomena and offered possible solutions, these were enriched by comments from the audience, including Terra Madre delegates from Senegal, Kenya, Cameroon and Benin, who described the dire situations in their own home countries.

Serena Milano, general secretary of the Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity, described how governments in Africa, Asia and Latin America are giving away millions of hectares of fertile land to countries who lack their own food or energy resources. Next to speak was Antonio Onorati, president of the Italian NGO Crocevia. To date, he said, 42 million hectares of land in the world are affected, an area more than three and half times the size of Italy.

Author of Il nuovo colonialismo (The new colonialism) Franca Roiatti explained in detail how land grabbing has been going on for decades but the spotlight was on the issue in 2007 and 2008 because of the global food crisis and rising food prices. With the world population expected to reach 9 billion by 2050 and arable land decreasing, land will soon become a very precious resource. Africa has much of the world’s arable land, and right now it is cheap. One hectare in Africa costs 300-500 dollars, said Roiatti, compared to 20 times as much in the US or UK.

Foreign investment in African land may sound good on paper, said Roiatti, but in reality agreements are often not transparent and countries’ legislation not strong enough to stand up to the power of multinationals. Regulations protecting foreign investments include clauses like the infamous “stabilization clause,” which prevents a state from changing its laws in a way that would endanger the interests of investors.

Drawing on a specific example from Ethiopia, Nyikaw Ochalla of the Anuak people, currently living in exile in the United Kingdom, talked about the complex land ownership system in his country before Mengistu seized power in 1974, and how in 1975 the military regime brought all land under state control. When the current regime came to power in 1991, they kept a similar system. “The Ethiopian economy has suffered a lot since the 1970s,” said Ochalla. “The Haile Selassie regime was overthrown because of famine. Has the situation improved since then?”

The answer, it seems, is no, with many still dying of hunger. “Why should the current regime be selling land when people don’t have enough to eat?” he asked. “The new landowners are growing flowers, jatropha for biofuel and food for export, while Ethiopians are starving.” Yet small-scale farming is the most important sector of the Ethiopian economy (agriculture is responsible for 45% of the economy and 85% of the labor force, he said).

According to Franca Roiatti, oil-producing countries concerned about their future food supplies are one of the culprits. “They’re worried that in the future, even with money to buy resources, they won’t find anyone willing to sell, she said. Then there are big agricultural producers like India and China. Despite its large agricultural sector, China began importing food in 2008, and Roiatti said this was partly because of the country’s growing middle classes and their changing food habits. Lastly, she said, investors have moved into buying land since the financial crisis, looking for an investment they can touch, tangible capital for their portfolio.

“So what can we do?” asked Onorati. Mobilization was the answer, he said, as well as laws and international campaigns. He hoped on-going negotiations with governments would lead to an immediate moratorium on land transfers, similar to those imposed on GMO crops. Serena Milano said Slow Food wanted to network everyone working on the issue, and said the biggest problem was that land grabbing was being ignored by the media.