In a country like Ethiopia where farmers have very limited access to the legal and credit institutions, and where farmers are marginalized from formal land rights and existing land uses, official statements that claim ample, idle, or unoccupied land are totally immature.

Ethiomedia | January 4, 2011

By Ephrem Madebo

Given Ethiopia’s acute poverty status, its dependency on food aid, and the ever changing global economic context; there is no doubt that Ethiopia’s agricultural sector must change fundamentally, and there is no question that such a fundamental change requires sizable investment.

Poor countries like Ethiopia are faced with a seemingly intractable dilemma – they have an urgent need of transforming their agrarian economy, but they are incapable of raising the necessary amount of capital. Hence, it is this fiscal constraint that has forced Ethiopia and many other developing countries to look for outside sources of capital. Obviously, capital is not free; therefore, the question here is what should developing countries like Ethiopia give in return for capital and how should they negotiate with the international power houses of capital?

Over the past two years, the unprecedented large-scale acquisition of farmland in developing countries has created national bitterness in the countries where land is grabbed, and curiosity and perplexity around the world. Internally neglected lands that had little or no outside interest until recently, are now attracting populace nations like China and India, emerging economies like Indonesia and Malaysia, and rich countries like Saudi and Qatar. This new phenomena is quickly changing the hitherto “North-South” order into the new “Rich-Poor” relationship. This economically and politically sensitive episode has the potential to create lingering social and political crisis in many developing countries because land is so central to identity, livelihoods, and food security. Hence, it is not a coincidence that a new catch-phrase – “Land Grab” – is coined to describe the current global outburst of farmland transactions that involve the production and sale of food items, biofuels, and minerals.

Today, land grab is a global occurrence; however, though the impacts of the global land deals have yet to be understood, the actual transaction of land grab affects the global south than any other zone. Despite the fact that the reactions sharply differ, governments, farming communities, transnational corporations, civic groups, and investment banks around the world have all reacted to the land grab. Evidently, huge investments associated with the land grab are sparking expectations and uncertainties among the affected communities. Some believe the deals can transform agricultural communities by boosting farm productivity. Yet, many others worry that land acquisitions are major threats to the lives and livelihoods of the rural poor who lack organization, information, and political voice.

Is it land sale or “Land Grab”?

As stated above, land grab is a global phenomenon, but the answer to the above question will be more realistic if individual land deals are assessed in the economic and political context of each country involved in the selling aspect of the transaction. If we consider Ethiopia, the land deal between the TPLF regime and the foreign buyers is definitely a “Land Grab” because the land is sold or leased for an extremely low price and the deals are negotiated behind closed doors.

Generally, when global land deals are negotiated in the interest of host countries, benefits from foreign land investment come in the form of technology transfer, employment creation, human capital development, infrastructure development, higher state revenues, and rural development – but in Ethiopia these commitments tend to lack teeth in the overall structure of documented land deals because:

A-There is a lopsided power relationship between the investing countries and the Ethiopian regime. Hence, as a food aid recipient nation, Ethiopia is not in a position to refuse any kind of investment deal.

B-The Ethiopian regime is in conflict with its own people, within itself, and with its neighbors; therefore, it is a very weak negotiator.

C-Smallholders who are being displaced from their land cannot effectively negotiate terms favorable to them when dealing with countries like India and China, nor can they enforce agreements if these countries fail to provide promised jobs or local facilities.

D-The objective of land buyers is not reconciled with the investment needs of Ethiopia, i.e. land investment is triggered by external demand to meet the food and energy supply of external markets (a new phenomenon known as agrarian colonialism).

E-Virgin lands in Ethiopia are sold for a mere fraction of the price they are worth and only God knows where the proceeds from the land sale go. Besides, domestic laws, rules, and regulations are modified to attract investment and investors are allowed to enjoy extended tax holidays.

F-Ethiopia lacks a clear and consistent national land use and foreign investment policies; it also lacks strict compliance rules for investors

What is the driving force behind the land grab?

Until recently, as recently as 2002, there weren’t that many governments or private companies rushing to acquire land in developing countries. No more! Global economic relations are changing for good - the recent unprecedented rush to virgin African lands by private investors, foreign governments, and transnational corporations has dwarfed the 1849 California Gold Rush. Towards the end of the 1840s, when the Europeans, the South Americans, the Australians, and the Chinese rushed to California, they all had gold in their mind; but the modern day “Forty-niners” see beyond or more than gold.

Some countries such Saudi, Bahrain, and Qatar have severe shortage of land and water and are highly dependent on food imports; therefore, for these countries overseas land acquisition is the major part of their national food security strategy. On the other side, populace countries like India, China, and South Korea are seeking opportunities to produce food overseas to mitigate their food security risk & concerns. Other factors that influence land investments include the production of biofuel and other cash crops. According to factors enumerated above, it is neither the domestic need for investment capital nor the excess land supply [as claimed by the regime] that triggered demand for Ethiopia’s rural land. The demand for Ethiopia’s land is created by global food and energy insecurity.

Each and every large scale land deal in developing countries is not explained by food security concerns; in fact, a good part of the land deal is driven by investment opportunities. In the last five years, rising agricultural commodity prices have made the rate of return in agriculture very attractive, and the high return rates in turn have made the acquisition of land for agro-production an increasingly attractive option. Moreover, relaxed regulatory, environmental, and tax laws in many developing countries [including Ethiopia] have improved the attractiveness of agricultural investment. As a result, many companies traditionally involved in agro- processing are now entering direct production by buying/leasing land in developing countries.

Are foreigners grabbing idle land in Ethiopia?

The regime in Ethiopia has repeatedly claimed that the land it is leasing for foreigners is unoccupied idle land; and in many instances, the regime has also justified its massive land sale on the basis that the land being acquired by foreigners is “unproductive” or “underutilized”. A legitimate question here is - how do we define an “idle” land? Is ‘idle” an assessment of land productivity, or non-existence of resource use? Be it for the purpose of animal grazing, hunting, or gathering wood for construction and energy, there is always some form of land use in rural communities. Well, since there is no monetary value attached to some types of rural land uses, it is true that such types of land activities are undervalued in official income or tax assessments, sending the wrong message to hasty government officials who think the land as idle or unused. But, land is always a valuable livelihood source to rural communities. Therefore, despite the government’s claim that it is leasing idle land, the current large scale foreign land acquisition in Ethiopia may further jeopardize the welfare of the poor farmers by depriving them of the safety-net function that this type of land and water use fulfills.

In a country like Ethiopia where farmers have very limited access to the legal and credit institutions, and where farmers are marginalized from formal land rights and existing land uses; official statements that claim ample, idle, or unoccupied land are totally immature. In fact, such faulty claims emanate from the regime’s strong determination to execute secretive political decisions that have less to do with the economic realities of rural communities in Ethiopia. Therefore, the argument of the Ethiopian government that asserts “we have ample land” must never be considered as a worthwhile assertion.

Ethiopia is the second most populace black country on earth and has the 9th fast growing population in the world. Whether the regime in Ethiopia acknowledges it is or not, Ethiopia is stumbled with a conflicting economic reality of a rapidly growing population and constant land quantity. Unlike the regime’s hollow claim of “Ample Land”, per capita land distribution in Ethiopia will significantly shrink as the size of the population increases. In fact, future problems of land shortage in Ethiopia are far more severe than said here. The current Ethiopian population is projected to be slightly more than double in just 39 years [2050]. This growing population needs habitat, food, healthcare, education, transport, communication and recreation services; and all of these services need land. So where is this land coming when Ethiopia’s population count reaches 200 million and beyond? No matter how efficient our economy becomes and no matter how productive our work force will be, we must be very careful in our land usage; and our current land usage must take into account future generations.

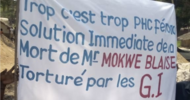

I don’t think there is a human being in Ethiopia, who is against economic development; and on the flip side, overseas farmland investment is not bad by itself. However, investments with such far reaching national consequences need to find win-win solutions; but no win-win solution can be reached when the land deals ignore the voice of the very farmers whose livelihood it is supposed to change. In Ethiopia, resentments over land grab have already started claiming lives. The TPLF regime that takes killing as the only method of conflict resolution has already killed 10 protesting ethnic Anuak farmers and has sent thousands more to concentration camps.

The Ethiopian population grows annually, and as the population grows real per capita farmlands continue to shrink across Ethiopia. The 2008 Central Statistics Agency report shows that over thirteen million small farmers open up over a million hectares of virgin land every year. Obviously, Ethiopia needs foreign investment to revolutionize its agricultural sector; but any effort to transform its agriculture must start from within making poor peasants the center of the transformation.

The current culture of secrecy that surrounds agricultural land deals in Ethiopia raises concerns over the conduct of the government in protecting the interest of poor peasants. Furthermore, the lack of transparency undermines government accountability and increases the opportunities for corruption and other inappropriate acts that the TPLF regime is known for. If the regime in Ethiopia is honest in what it is doing, the process of transforming Ethiopia’s agriculture must go hand in hand with the following very important preconditions:

A-The farming community that uses the land must be highly motivated to use it well, and since nothing motivates farmers than owning land, farmers must be allowed to own land.

B-Develop a clear and consistent national land use policies and strict compliance rules for investors

C-Create rural micro lending institutions. To transform the agricultural sector, trust local farmers, not foreigners

D-Make sure that the government, the civil society, and the media have the right tools in place to ensure that foreign investments improve productivity and increase rural standard of living [not cause harm]

E-Take advantage of the overseas investment opportunities, but make sure that foreign investors are not the driving forces of the government’s development strategy

F-Respect existing land rights, including customary property rights. Involve civic societies and farming communities in land deal negotiations and makes the negotiations are transparent

G-Consider ecological consequences and Environmental problems of large-scale agriculture in every land deal negotiation

H-Compensate displaced framers with comparable and enough funds that make the new beginning enjoyable

Finally, let’s all keep in mind what Mark Twain said: “Buy land, they don’t make it anymore”. Yes, the prudent quote says “buy”, not sell. Let’s do things wisely and responsibly, and let’s not sell our land for everybody that comes with a bag of money. In Ethiopia, land has ancestral value and it is the great connector of lives, it is the source wealth, pride, and destination to all. Our laws change and we the people die, but the land remains – Lets not tamper with this law of eternity.

References

Lorenzo Cotula, Sonja Vermeulen, Rebeca Leonard and James Keeley, Land Grab or development opportunity? Agricultural Investment and international land deals in Africa

Joachim von Braun and Ruth Meinzen-Dick, “Land Grabbing” by Foreign Investors in Developing Countries: Risks and Opportunities

Ernest Aryeetey, African Land Grabbing: Whose Interests Are Served?

Ruth Meinzen-Dick, Necessary Nuance: Toward a Code of Conduct in Foreign Land Deals

____

Photo courtesy of Turkairo at Flickr.com (http://www.flickr.com/photos/7838055@N05/2471082718)