Indrani Bagchi, TNN

Ramakrishna Karuturi does not feature on any international power list. Perhaps he should. A new UNCTAD (UN Conference on Trade and Development) report names Karuturi Global Ltd as one of the top 25 agri transnational corporations in the world. Another report, by the International Food Policy Research Institute, says he owns one of the world's largest landbanks -- over 3,000 sq km. In a conversation with The Times of India, he claimed, "I'm the largest landbank holder in the world."

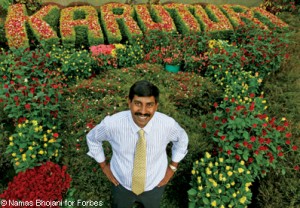

Karuturi's modest floriculture business outside Bangalore really blossomed when he discovered faraway Ethiopia in 2004. The African country welcomed the industrious Indian farmer and in the span of a few bountiful years, KGL has grown to become the world's largest producer and exporter of roses.

The 43-year-old engineer-MBA is now venturing beyond Ethiopia and the rose. In 2007, his company acquired Sher Agencies in Kenya, the world's largest rose farm, which incidentally employs four national football players. Then, last year, KGL bought more land in Ethiopia for sugarcane, staples, coffee and palm oil. And now, he's set to enter Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

KGL is one of the pioneers of what Japanese financial services giant Nomura Securities calls "the third wave of outsourcing". With world consumption of foodgrains having outstripped production in eight of the last nine years, and cultivable land increasing at a negligible 0.27% per annum, the spectre of a serious food crisis and spiralling prices is very real. Food import bills have already risen about 25%. Indian consumers, too, have been hit hard by soaring food prices.

In a breathtakingly ambitious bid to ensure food security, a number of countries -- particularly those that are cash-rich but land-poor -- are buying up enormous swathes of farmland in the poorer nations. In the last one-and-a-half years alone, over 33 million hectares of prime agricultural land in dozens of developing countries have been snapped up. That's roughly the size of Germany.

The land is used to produce food, fodder and fuel, which is transported back to their own countries for home consumption (and partly for third-country sale).

Sensing a great opportunity for profit, private agri-business companies and investment/hedge funds have joined sovereign nations and state-sponsored corporations in the land-buying spree, as have a number of automobile manufacturers who are exploring biofuel alternatives to petrol, diesel and gas.

There have been several cover stories on the global race for the earth's treasures, from oil and gas to coal, iron ore, bauxite (for aluminium), zinc, copper and gold — a race India's very much a part of, but one that China's clearly winning as it uses its huge financial reserves to take over mines and mining companies across continents.

It's the stampede for land that promises -- or threatens, depending on your point of view -- to reshape the map of the world, and its geopolitics.

Analysts estimate that over $60 billion has been committed to acquire land and establish farms to produce foodgrains, oilseeds, and biofuel crops. These eye-popping numbers could be just the tip of the iceberg, since most deals are cloaked in secrecy.

Attempts to keep such mega acquisition under wraps is understandable, given the rising tide of opposition to what is seen as a new form of colonialism. The growing fear of 21st century East India Companies grabbing vast territories and controlling the lives of local populations has begun to give governments and politicians the jitters. Land acquisition is a politically explosive issue -- one has only to recall the rioting in Singur when the West Bengal government acquired land for the Tatas to start a small-car plant.

In Madagascar, the Ravalomanana government was overthrown after it was revealed that it had handed over 1.3 million hectares -- about half its total arable land -- to Daewoo Logistics of South Korea to grow corn, a Korean staple. The new Rajoelina government not only cancelled the highly unpopular contract, but within days of assuming power, found yet another deal crawling out of the woodwork: a Mumbai company, Varun International, had negotiated for 170,914 hectares in Madagascar's Sofia region to grow rice, corn, wheat and maize. (A spokesman for Varun said they were still optimistic. "Talks are on and our chairman, Kiran Mehta, is expected to travel to Madagascar in a fortnight.")

Mindful of India's long struggle to free itself from British bondage, New Delhi has carefully avoided any overt role in this rising wave of 'neo-colonisation'. But in the face of China's aggressive push into foreign soil, it's beginning to shed its old reticence, particularly in smoothening the way for Indian firms, mostly in the private sector, to join this scramble for soil.

"We are now in talks with Namibia, after their President's visit, to use land for our purposes," minister Shashi Tharoor said when The Times of India asked him for the external affairs ministry's view on the subject. Jairam Ramesh, who was in commerce before becoming environment minister, told this paper, "Yes, we're definitely looking at leasing land in African and Latin American countries. A lot of these countries have asked for Indians to participate." The agriculture ministry, too, is more than happy to support companies in their overseas farming operations.

Indeed, Indian companies are striking lucrative deals thanks to some inspired diplomatic work by Indian envoys in a number of countries. Sudan, which has already given large tracts to Saudi Arabia and China, has been asking India to buy some of its land -- Darfur, for instance, is very fertile. But that's a hot potato India isn't keen to touch.

In Ethiopia, the government has given over $800 million for sugar development -- India's largest-ever funding for such projects. It's perhaps no coincidence that in August, Delhi-based Uttam Sucrotech won a $100-million contract to expand the Wonji-Shoa sugar factory in central Ethiopia.

The land rush so far has largely been to Africa, but for India, Latin America is the new frontier. The flat prairie lands of Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay are ideal for oilseeds and pulses, both of which India is severely short of. There are several advantages of Latin American landholdings, India's ambassador to these countries, Rengaraj Viswanathan, told TOI. The governments are themselves inviting companies to buy or lease land for agriculture; there are fewer political sensitivities here, unlike the fears of colonisation in Africa; the yield per acre is three times that of India; and they are blessed with steady rain.

Signficantly, the public sector State Trading Corporation is learnt to be looking at land in Peru to cultivate tur dal.

The Solvent Extractors Association, the Indian oilseeds industry body, has formed a consortium of 18 companies to acquire 10,000 hectares of prime farmland in a $40-million deal in Uruguay and Paraguay to cultivate oilseeds and pulses. The association CEO B V Mehta said they are hamstrung only by access to finance, otherwise they have it all sewn up.

Simmarpal Singh of Olam International (based in Singapore and controlled by Sunny Varghese) went to Argentina in 2005 to buy peanuts for Olam, but ended up growing them on 12,000 hectares of land, earning him the sobriquet of Peanut Prince of Argentina. Thanks to his colourful turbans, and maybe the fact that he acquired 5,000 hectares to grow soya and corn, he's now known on the night club circuit simply as the 'Prince'. His IIT-Delhi wife Harpreet Kaur smilingly dismisses stories that Simmarpal enjoys preferred client status at night clubs, saying he works too hard to find time to party hard (though he does have time for golf).

There are a whole lot of other Indians in Argentina (one of the world's largest producers/exporters of peanuts, sunflower oil, soyabeans, biofuels) and other parts of Latin America who may not be as flamboyant as Simmarpal, but are no less driven. The Chennai-based Sterling Group has an olive farm over 1,700 hectares. Arumugam, a Tamil-Malaysian entrepreneur, owns 600,000 hectares of land in Argentina for production of oilseeds.

India's growing presence abroad hasn't gone unnoticed. The Guardian, in a recent article, wrote, "India has lent money to 80 companies to buy 350,000 hectares in Africa." And there are reports that Indian companies are eyeing not just Africa and LatAm, but countries nearer home, such as Myanmar, as well as those further afield, like Australia and Canada.

Does India really need land other than its own for farming? After all, it has the second-largest area of arable land (160 million hectares) after the US (174 mha). But the picture turns bleak when you consider arable land per capita: we rank 104th with 146 hectares of arable land per 1000 people (compared to Australia's 2,430 ha). Also, remember that only about half our cultivable land has access to irrigation; for the rest, farmers have no option but to put their faith in the rain gods, and that can make a difference of a hundred per cent in terms of yield. Finally, there's the problem of small and fragmented land holdings that deprives farming of economies of scale and makes it unproductive.

But China is in a tighter spot than India. It ranks No. 4 in terms of total arable land, but as a share of total land, it's just 11% compared to India's 56%. As for arable land per capita, it figures even further down the chart at No. 144.

Small wonder that China is among the frontrunners in the land race along with other food-importing countries like Saudi Arabia, the oil-rich Gulf states (Qatar, Abu Dhabi, Bahrain), South Korea and Japan. According to IFPRI, the food crisis of 2008, along with "increased pressures on natural resources, water scarcity and export restrictions imposed by major producers when food prices were high, and growing distrust in the functioning of regional and global markets" is driving these nations to seek arable land wherever available, preferably near ports.

Saudi Arabia, after the huge spike in food prices in 2007-08, decided that it couldn't possibly eat oil, and is venturing into Pakistan, among other obliging nations. Pakistan has offered thousands of hectares of farmland in all its four provinces to Saudi Arabia to grow wheat, fruits and vegetables. The Saudi deal was announced by Pakistan PM Yousuf Raza Gilani after a June visit to the desert kingdom, and the deal is expected to be sealed in the next few months. Not just that, there are reports that the land given to the Saudis will be protected by the Pakistan army. Pakistan is also in talks with Qatar to offer land in Punjab, its most fertile province. Some reports say that 25,000 villages will be displaced if the deal goes through. And just as we were going to press, South Korea announced a deal to develop 1,000 sq km of land for cultivation in Tanzania.

What has provided a tailwind to this global shopping trip is the entry of private investment funds. After the ruinous downturn in stock and derivative-based wealth last year, several fund managers began to think of agricultural land as the promised land. According to a Rabobank report, over 90 funds are currently active in investing in agriculture. These funds have snapped up land in Africa, South America, and the steppes of Russia and Ukraine. Leading investment firms like Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs have even moved to livestock and invested in Chinese poultry and pig farms. But as farmland becomes a strategic resource along with oil, water and minerals, it's opening the door to political and social unrest. There is already opposition from Cambodia, Thailand, Ethiopia and Mozambique; in Pakistan, the Balochis have forced their government to tear up a farm deal with the UAE.

Since most of the land-fertile countries are poor and politically fragile -- and often not able to feed their own people -- the parcelling out of land to the highest foreign bidder gives a new meaning to the term 'banana republic', the derogatory sobriquet originally used for servile dictatorships who abetted the exploitation of plantation agriculture by MNCs like United Fruit Co in Honduras. Africa, squatting always at the bottom of the food chain, is rapidly being turned into a giant land mall. The irony of a famine-prone continent being used to bail out the world's food crisis is lost on no one. David Hillam, deputy director of the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO), brought these fears up front when he told a conference in Washington, "Imagine empty trucks being driven into, say Ethiopia, at the time of food shortages caused by war or drought, and being driven out again, full of grain to feed people overseas...Can you imagine the political consequences?"

Those who see the trend as a positive argue that hitherto under-utilized land is coming under modern agriculture, thus making it far more productive and increasing the food-production base. Counters Devinder Sharma, an analyst with the Forum for Biotechnology and Food Security: "Outsourcing food production will ensure food security for investing countries but will leave behind a trail of hunger for local populations...The environmental tab of highly intensive farming -- devastated soils, dry aquifer, and ruined ecology from chemical infestation -- will be left for the host country to pick up." That's quite apart from the fact that locals do not gain from the increased productivity since the output doesn't accrue to them.

Proponents of this new land rush also say foreign investments in land will create jobs for locals, improve living conditions and increase GDP. The facts don't support such claims. For instance, in Ethiopia, one of the world's poorest countries, over 600,000 hectares have been leased out to investors at about $3 to $10 per hectare per year. The average landholding size is about 2 hectares. Thus over 300,000 families are displaced. But only about 20,000 people are expected to get jobs in the highly mechanised farms. The Chinese have tried to contain opposition to their surge overseas with the same strategy they have used for acquiring mineral rights. They throw in a lot of sweeteners like building roads, hospitals, bridges, dams and ports.

Clearly, there's a growing and insatiable appetite for land. The trajectory is exciting and could change the contours of global commodity markets, land economics and geopolitical equations. For the one billion under-nourished people, the implications will be profound: those in countries with arable land may well wish they had oil instead of water under their feet.

As for India, a time may soon come when it will need to take a call on whether it should join the race in real earnest or continue to provide quiet support to its growing band of peanut princes. Funding of overseas land acquisitions remains an obstacle. "We are trying to persuade the Exim Bank to lend us Rs 250 crore for this," said Mehta, who's heading the consortium that plans to acquire land in South America. But the Indian banking system has not yet figured out a way to facilitate the acquisition of such land. Top officials at Exim Bank said that while there was no bar on Indians acquiring land overseas, domestic banks had no way of financing such deals. But given the growing interest in this sector, bankers are even willing to look at innovative solutions to the financing crunch. As one official explained, on condition of anonymity, "You won't be able to get your bank branch in Connaught Place to finance such ventures, but the branch in Mayfair, London, might be able to."

As this high-stakes game evolves, so will the rules.

(With Subodh Varma)